Millions of families 'worse off' than 15 years ago

PA

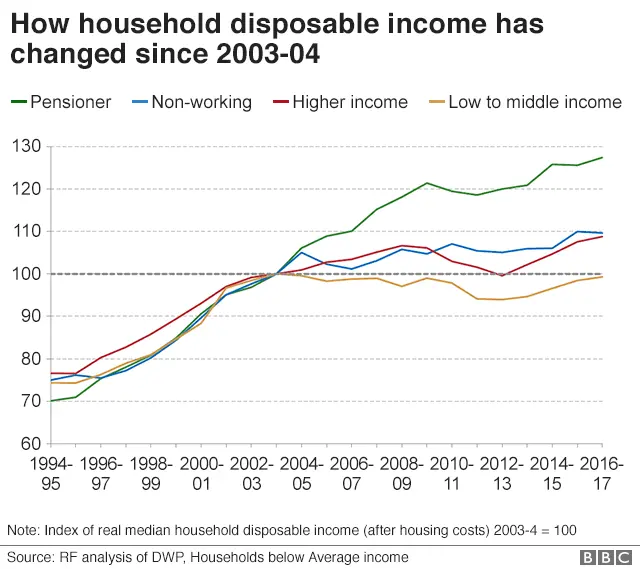

PAMillions of "just about managing" families are no better off today than those in 2003, new research from the Resolution Foundation indicates.

The remarkable income stagnation for so many reveals that the economy has been failing to generate income for people over many years despite record levels of people in work.

In 2003, households on the lower half of incomes typically earnt £14,900.

In 2016/17 that figure had fallen to £14,800, the research shows.

Both figures are adjusted for inflation and housing costs.

There are over eight million low and middle income households, just under half of which have children.

And it is not just poorer households which have been facing a pay squeeze.

On average, incomes for all households in 2017/18 increased by just 0.9%, the lowest rise for four years and less than half the average between 1994 and 2007, just before the financial crisis.

For the poorest third of households, incomes actually fell by up to £150 in the last year.

The Resolution Foundation report said that surveys revealed that over 40% of low to middle income families feel they would be unable to save £10 a month and over 35% would be unable to afford a holiday for one week with their children.

"We appear to have a picture of generalised stagnation for many, with lower income households actually going backwards," the Resolution Foundation's Living Standards Audit says.

"The apparent falling away of the bottom from the middle in 2017/18 represents a disturbing new development.

"This pattern has clear implications for poverty - captured by the number of people living in households with incomes below 60% of the median [the middle figure of a set of income figures ranked from high to low].

"There are good odds that 2017/18 delivered a notable increase [in poverty].

"Relative child poverty may have risen to its highest rate in at least 15 years, despite high levels of employment."

"Child poverty" is calculated by the number of under-16s living in a household that earns less than 60% of the average income.

The big questions are why the income stagnation has happened and what can be done about it.

On the "why", research by the Foundation - which was set up to look at the problem of low incomes - reveals that the economy has struggled to create wealth for people in work.

Although employment rates are high, which is good for those in work, many of the jobs are lower paid.

That's because people who are moving from unemployment into employment, such as single parents, tend to take jobs towards the lower end of income levels.

Once in jobs there is also a lack of "progression" into higher paid jobs.

Productivity puzzle

Productivity levels for the whole economy - the ability to create more value for every hour somebody works - have also been poor since the financial crisis.

Rather than investing in new innovations - such as computer technology or robots which could increase the amount people produce - firms have been holding onto cash to get them through the tougher economic conditions.

What are called "non-wage costs" have also increased.

Businesses now have to pay more into employees' pensions and, for larger firms, have to pay costs such as the apprenticeship levy to encourage better standards of training.

Managers have also been criticised for being too conservative about taking on new ways of working.

Benefit cuts since 2010 also affect lower income households far more than those on higher incomes.

Put those factors alongside the poor economic growth the UK has been experiencing, along with many other developed Western economies, since 2008 and the reasons behind the living standards problem become clearer.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen it comes to solutions, the key is productivity.

Economists argue that once in work, people should be encouraged to apply for promotions, increasing their skill levels and their pay.

Firms should be encouraged to invest in innovations to make their firms more efficient and better able to create wealth for every hour worked.

Better economic growth, which leads to higher incomes, is reliant on a number of factors - certainty about the future (in relatively low supply at present because of the Brexit process); global growth (Britain is an exporting nation so the better growth is elsewhere, the better for the UK); and investment in better and higher-value skilled jobs (which means focusing on education and skills and making managers better at exploiting opportunities that are available).

Without a firm focus on such issues, the Resolution Foundation report reveals that, over the next decade, it is likely that "just about managing" families are likely to remain just that.