Coronavirus: Big choices for EU leaders on recovery billions

Reuters

ReutersWhen the leaders of the EU27 gather in Brussels on Friday be prepared for the shock of the familiar. After five months of stilted diplomacy by video conference, presidents and prime ministers will once again gather face to face.

Although of course that doesn't mean they'll see eye to eye.

Expect plenty of face masks and plenty of displays of social distancing to go along with the rather obvious political distancing which has emerged in the long months of lockdown.

European Council

European CouncilAnd it's not just the sight of the EU's leaders gathering in person which will seem familiar, it's the problems they confront.

What must they decide?

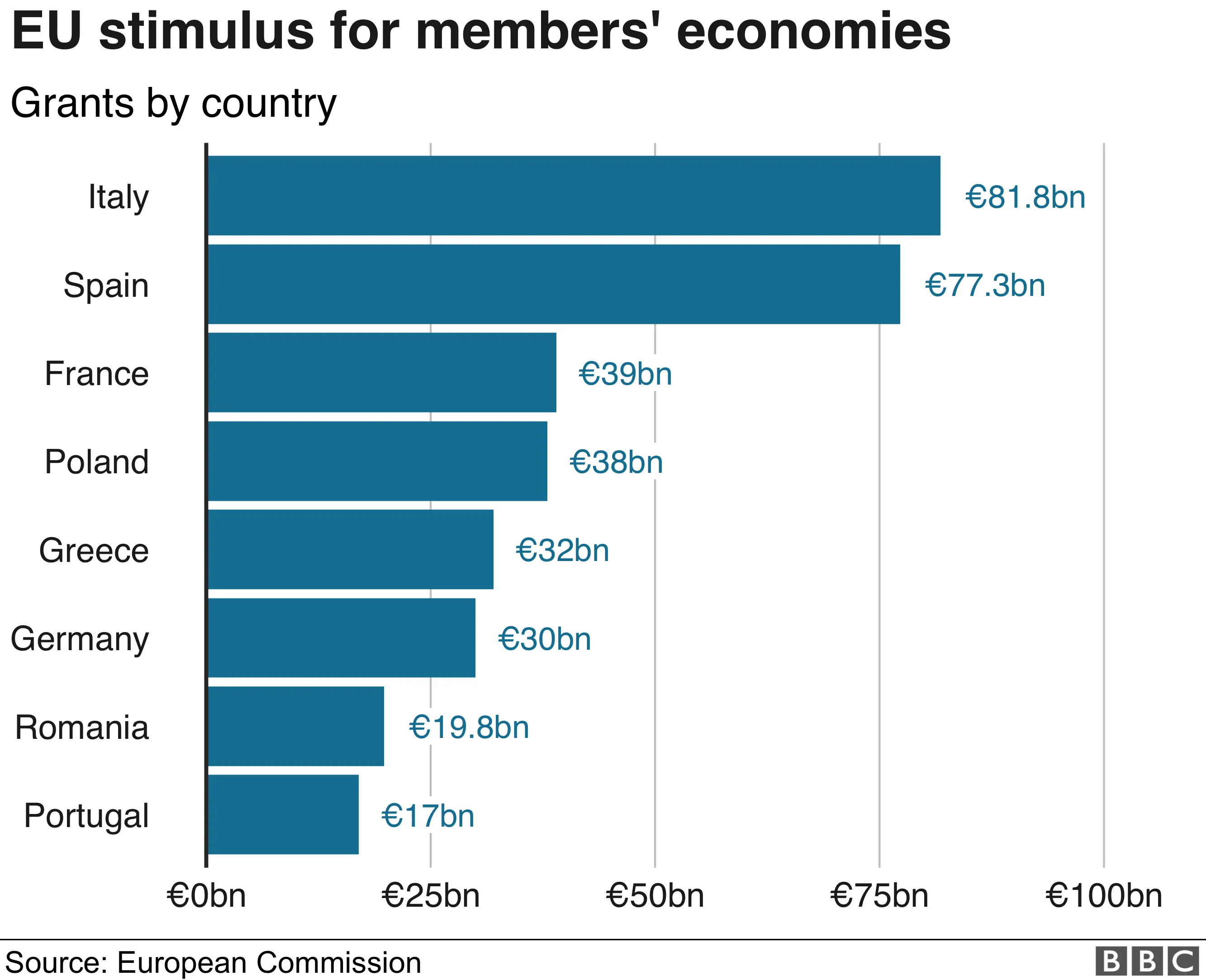

On the face of it the summit is about money: they need to set an EU budget of around €1 trillion for the period ending in 2027 and at the same time to agree an ambitious €750bn (£670bn) Recovery Fund.

For the big Brussels institutions, the European Commission and the EU Council there is a lot at stake in all of that - not least their own centrality in European political life.

As the coronavirus pandemic began to hit Europe earlier in the year, member states responded not as a unified entity under the direction of Brussels but nation by nation with each government putting the interests of its own people first.

Team Luftwaffe

Team LuftwaffeBorders were closed with little or no consultation, emergency economic measures were introduced without central co-ordination and when Italy requested emergency medical help the response was underwhelming.

Things improved - German hospitals treated French patients for example - but Brussels is determined that just as it lost control as Europe slipped into crisis, its own centrality will be restored as the continent re-emerges.

That will take money - and lots of it.

Who are the 'frugals'?

One of the eternal truths of political life in Brussels is that expensive spending programmes are more popular with the countries that expect to get money out of them than they are with the countries expected to put it in.

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte is often presented as the chief spokesman of the so-called Frugal Four, in which his country is allied with Austria, Sweden and Denmark.

Throw in Finland and you have a Frugal Five determined to limit the size - and therefore the ambition - of any budgetary increases.

Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin says her government wants to see "a lower overall level (for the budget) and a better balance between loans and grants (in the recovery fund)".

Finnish Government

Finnish GovernmentCompare that with the view of Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, who puts the opposite view with admirable clarity: "If we want to be very ambitious we will need more resources."

The EU faced plenty of challenges before Covid-19 came along of course - Brexit, climate change and the continuing challenge of migration from the South come to mind.

But this row over money feels different - it's about the scope and scale of the EU's ambitions stretching far into this decade and perhaps setting a tone for years beyond that.

Who should get the money?

"What's at stake," a retired diplomat told me, "is the ability of the EU institutions to get a grip and to turn crisis into opportunity."

It may not be helpful in all of this that the institutions are in relatively inexperienced hands - the former German defence minister, Ursula von der Leyen, at the Commission and a recent prime minister of Belgium Charles Michel at the Council.

But it's only fair to note that the challenges around these budget talks would have taxed even the most experienced of teams.

That's because this is not a problem that can be solved by holding the multi-year budget a shade below €1.1tn than a shade above, or by knocking a couple of billion off the recovery fund.

Should the money simply be shovelled out to the needy or should there be some sort of scrutiny of applications for help and oversight as to where the money goes?

Southern and Eastern member states will resent any implication that richer and somehow more "grown-up" economies to the North and West are telling them how to manage their affairs.

And even more controversially should the handing out of funds be linked to political values?

Many in Brussels think countries like Poland and Hungary should only get money if they abandon policies on judicial reform seen by their critics as assaults on the rule of law.

Hungary's leader, Viktor Orban, has now secured the backing of his parliament to veto the whole budget if there's any linkage between money and morality.

In the age of Brexit there's no voice for the UK in all of this of course - its absence might weaken the fiscal conservatives but might also streamline the whole argument.

Don't expect quick decisions or short discussions - there is scope in the institutional diary for another summit before the end of the month.

The EU's leaders had to wait five months for this summit - it's a fair bet they won't have to wait so long for the next one.