Coronavirus: Why Gujarat has India's highest mortality rate

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn 20 May, Parveen Bano started to feel slightly breathless. When she told her son, Amir Pathan, he rushed her to the nearest hospital.

He says he was worried because his 54-year-old mother had diabetes and a history of cardiac ailments. And worse, their neighbourhood - Gomtipur in the Indian city of Ahmedabad - had recorded a slew of Covid-19 infections recently.

The next 30 hours were harrowing for the family. Mr Pathan says they went to three hospitals - two private and one government-run - but none of them had a bed available.

So Mr Pathan decided to bring his mother back home. But he says her "discomfort" worsened through the day and the night, so early the next morning, the family took her to Ahmedabad Civil Hospital, one of India's biggest government facilities.

She was swabbed for a Covid-19 test, and put on oxygen support because doctors found that her blood oxygen levels were low. Mr Pathan says the levels were erratic through the day, so doctors connected her to a ventilator that night.

Hours later - at 1:29 AM on 22 May - she died. Her coronavirus test result came the next morning - it was positive.

The hospital did not respond to the BBC's queries, but Mr Pathan says he believes his mother may have lived if she had been admitted to a hospital a day earlier.

The Ahmedabad Civil Hospital has made headlines time and again as it struggles to cope. The high court has referred to it as a "dungeon" and cited the number of Covid-19 deaths - 490 - it has recorded so far. And the court has also rebuked the state government for its handling of the pandemic.

But the government has denied any laxity on its part.

What is driving Gujarat's high mortality rate?

Ahmedabad, home to more than seven million, is the largest city in the western state of Gujarat.

It's also the worst-affected by the pandemic, accounting for more than 75% of the state's caseload, and nearly all of its deaths.

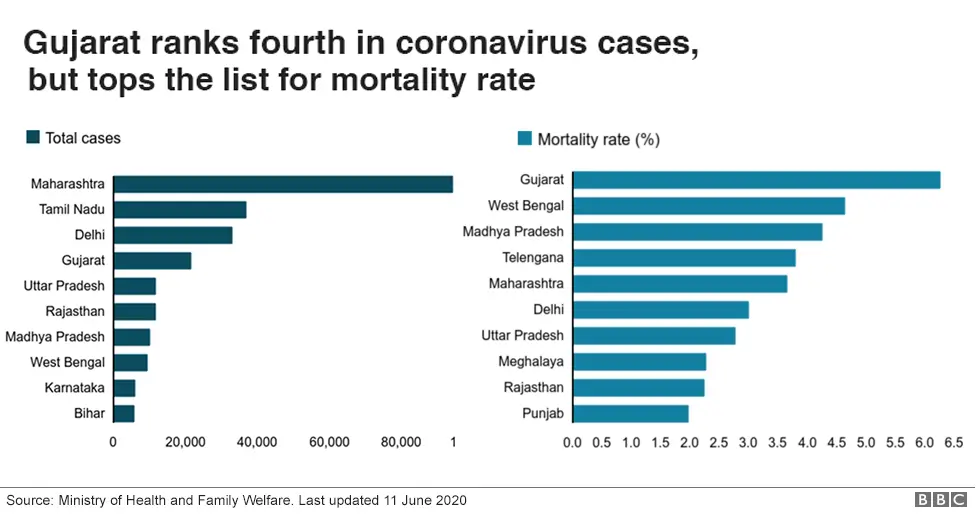

With more than 21,500 confirmed cases, Gujarat has India's fourth highest caseload. But the state's fatality rate - the proportion of Covid-19 patients who have died - is the highest at 6.2%. This is more than double the national average of 2.8%.

When Gujarat's high court expressed "concern at the alarming number of deaths in Ahmedabad hospitals", the state government said that more than 80% of those who had died suffered from comorbidities, or other ailments, which made them more vulnerable.

But public health experts say it's hard to pin down a single reason for the mortality rate.

While some point to the state's high disease burden, others say that it's not unique to Gujarat - in fact Tamil Nadu has more diabetics than any other state, but its mortality rate is far lower.

Questions have been raised over whether India is under counting Covid-19 deaths but, if that were the case, there is no evidence to suggest that Gujarat is an exception.

Vijay Rupani, the state's chief minister, has repeatedly blamed international travellers and those who attended a religious congregation in Delhi, which later turned into one of India's biggest clusters so far.

But neither of these factors are unique to Gujarat - Kerala saw a greater influx of foreign returnees, and Tamil Nadu traced back far more people to the congregation. And while this may explain the surge in cases, it doesn't explain the disproportionate number of deaths.

Low testing, a lack of faith and stigma

"People reporting late to hospitals can be one of the major reasons," says Bharat Gadhvi, head of Ahmedabad Hospitals and Nursing Homes Association.

With private hospitals either refusing or unable to admit Covid-19 patients, many have been reluctant to seek treatment in government hospitals, doctors say. The reasons include poor facilities as well as a lack of trust in the quality of care.

Doctors have said stigma could be a reason too. Dr Randeep Guleria, head of India's biggest public hospital, referred to this after meeting doctors at the Ahmedabad Civil Hospital staff in May.

"One important issue that was discussed is the stigma attached to Covid-19. People still fear coming to hospitals to get tested."

May saw a jump in hospital admissions, possibly because of increased screening and testing, which led doctors and officials to identify potential "super spreaders" - such as fruit and vegetable vendors, and shopkeepers.

But public health experts say testing was still low in parts of the city, especially in what they call the "old city", parts of which are walled off.

"The government showed a lack of focus in dealing with the situation, especially in containment zones," says Kartikeya Bhatt, an economics professor.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe says 10 of 11 zones in Ahmedabad's old city were containment zones, and they all are densely populated.

He adds that while these areas were cut off from other parts of the city, officials didn't do enough to check the spread within the zones themselves.

"Physical or social distancing is next to impossible as people even wash clothes and utensils outside their homes," says sociologist Gaurang Jani.

Experts suspect that the infection spread rapidly in these parts, and due to stigma or poor awareness many people may not have sought hospital admission soon enough, according to an analysis by the Observer Research Foundation.

An overwhelmed city

But even those who survived the virus say the city's hospitals are not equipped to handle the crisis.

"Only after hours of waiting could I get a hospital bed," says Laxmi Parmar, 67, who was treated at Ahmedabad Civil Hospital's Covid-19 ward for 10 days.

"There was no breakfast in the beginning and I had to complain to a local politician to intervene. We had two toilets to share between 40-50 patients in the ward."

Experts say the pandemic has exposed the state's poor health infrastructure.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Otherwise, no-one would have bothered to know the state of hospitals in Gujarat. Now that shortage of doctors and paramedics is out in the open, we saw quick hiring happening even during the lockdown," Professor Bhatt says.

Gujarat only has 0.3 beds for every 1,000 people, below the national average of 0.55, according to a recent Brookings study.

And the surge in cases has led to a shortage of hospital beds, PPE kits and quarantine facilities. In recent weeks, Gujarat has been overtaken by Tamil Nadu in total number of infections but the situation still appears dire given the steep mortality rate.

"I disagree that we have failed in our duties," the state's health minister, Nitinbhai Patel, told the BBC.

"We currently have 23,000 hospital beds ready in the state and our medical staff are working around-the-clock in each hospital. We are also providing them with the best medical equipment to handle the situation which is slowly coming under control."

But his government has been criticised for what many see as a squandered opportunity because Gujarat recorded its first case as late as 19 March, just days before the country went into lockdown.

"Government policies could have been much better. Testing and isolation facilities appeared robust initially but have weakened with time as the administration appears tired," Mr Gadvi says.