Cancer patients 'should benefit from tailor-made treatments'

BBC

BBCPatients with cancer and other diseases in Wales should benefit in future from revolutionary, personalised treatments, the health minister believes.

Scientists will be able to analyse more quickly and precisely how tumours behave - and how each patient reacts.

It means treatments can be designed around each individual.

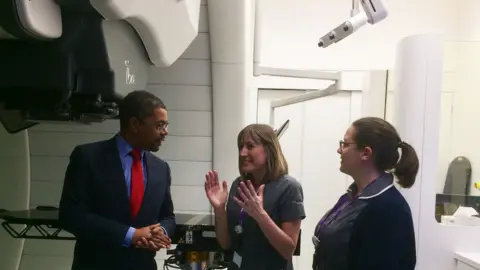

Vaughan Gething has set out his ambition for Wales to become a "global player" in precision medicine and gene therapies.

"We know this is the future of medicine and we know we'll get left behind if we don't do this," he said.

He said there were both "necessity and opportunities" about Wales being at forefront of personalised medicine, as he officially opened the UK's first high-energy proton beam therapy centre in Newport.

Precision medicine aims to treat patients as individuals based on our genes and body's biochemistry.

It is based on the principle that no-one is exactly the same - while scientific and technological advances mean more can be done with cutting-edge machines and genetic analysis to find out what is wrong with us and provide tailor-made treatments and therapies.

The first NHS Wales patient to get proton beam therapy

A year ago, Ryan Scott, 23, from Llechryd in Ceredigion was suffering headaches and bad neck pain and went to A&E in Haverfordwest, where they initially thought he had a virus.

But while he was there, he had a funny turn. A scan revealed a brain tumour, close to the optic nerve.

"I knew there was something wrong but it was quite a shock to hear it was a brain tumour. I had three major operations and they got most of the tumour out, but there was a little bit left."

His specialist suggested proton beam therapy, which was just being introduced into Wales. This is a specialist form of radiotherapy that targets certain cancers very precisely.

Protons are generated in a particle accelerator and fired at a tumour at very high speeds - as much as 100,000 miles per second - but stop when they reach the tumour and so are less invasive to the rest of the body.

Huw John, Cardiff

Huw John, CardiffRyan thought he might have to go to America at first but at the end of last year, the recently-opened Rutherford cancer therapy centre in Newport, a private clinic, was given the go ahead to take NHS patients. And so in February, Ryan became the first.

"I didn't feel anything once I was in there," he said. "I was lying on a bed and it took longer to make sure I was in the right position - I think it was only five minutes maximum for the treatment. It sounded like a printer would."

Ryan, who works for the family timber frame business, said he felt "privileged" to be the first to receive the therapy on the NHS. He said he is now "getting there" and waiting for his final scan. "Hopefully, it will be good news," he added.

How can precision medicine help?

Scientists in Wales say it is already an exciting time to be here with developments so far.

Prof Ian Weeks, dean of clinical innovation at Cardiff University's school of medicine, said it was already possible to make diagnoses earlier and more accurately.

"Precision medicine is becoming extremely important to try to diagnose more precisely - in molecular terms, what the cancer is," he said.

So it's not just about the shape and size of a tumour, but what it is actually doing and how it behaves and responds to treatment.

"There are many biochemical mechanisms causing it and unless we can understand and diagnose those we can't put the correct interventions in place," said Prof Weeks.

"By looking in more detail at the patient's biochemistry we can predict which drugs or therapies the cancer will be more responsive to and also those the patient may not take to awfully well."

Rhian White, clinical lead with the All Wales Genetics Laboratory said analysis of genes is also improving and it is no longer one type of treatment for one type of tumour.

"As years have moved on and into the future, we're able to look at vast numbers of genetic changes in a much wider range of cancers," she said. "This has given much more information to doctors and nurses treating a patient, enabling them to pick very specific types of treatment for their tumour which has a genetic make-up specific to them."

Tests on sequences of genetic mutations - in leukaemia, for example - which once took weeks can already be done in days. And the latest machine is now able to do the same work inside a day.

"It's only going to get faster," added Ms White.

Analysing our genes in detail can also help predict the risk of certain diseases developing, not just cancer but schizophrenia, Alzheimer's and other neurological conditions.

The Welsh Government is providing an extra £2.3m this year for new genetic tests and £2m towards plans for new diagnostic and advanced medical services.

Mr Gething said: "Cell and gene therapies have the potential to offer revolutionary solutions and bring benefits to patients affected by diseases for which no cure currently exists."

He said he was keen that Wales is at the forefront of developments.

In the long run it could also save money for the NHS.

At the moment, decisions are made on whether particular drugs or treatments are affordable for the wider population or a particular group of patients. But in future, perhaps, we may be looking at analysis of what is best suited for each individual.