Queen Elizabeth II: The Queue and the Cumbria expert who helped plan it

EPA

EPAThe queue of people patiently waiting to pay their respects to the Queen as she lies in state in Westminster Hall has become a talking point around the world. The people populating its five-mile length are willing to shuffle slowly along for between nine and 24 hours, sometimes overnight. The fact that it all works is down to a team of crowd science experts and a professor from Cumbria.

It has become known, simply, as The Queue.

Those watching its calm progress towards our former monarch - and it makes for strangely compulsive viewing - marvel at both its length and the stoic patience of those in it.

It is idiosyncratically British, they say. Who else would willingly join a queue that lasts longer than the average working day? And it comes with its own ecosystem. There is a live online queue tracker, coloured wristbands, toilets.

That it works is down to, among others, Prof Keith Still, from Burton-in-Kendal, Cumbria, who has been teaching and advising on crowd science for 30 years.

Planning for something like The Queue takes "decades", he says.

PA Media

PA MediaHe has provided analysis and advice and reviewed plans for not only The Queue, but also the Queen's journey from Balmoral through Aberdeen, where he was born.

Asked if he ever anticipated The Queue could reach five miles long, he replies, swiftly: "Yes."

The Queen was so loved, and reigned for so long, it was clear to him she was bound to have more people wanting to pay their respects than the 200,000 who gathered for the Queen Mother.

"You always plan for what might arrive and then five times that, and 10 times that," he says.

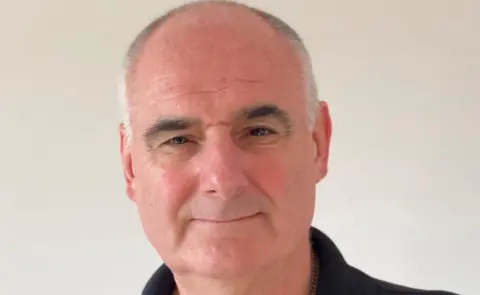

Keith Still

Keith StillThe Queue is remarkable for mostly being good humoured. There have been few reports of queue jumping or problems. As Prof Still puts it: "The crowd itself is looking after people within it."

While this may be due to the sombre occasion, human nature and the psychology of queuing behaviour must also be considered, he says. People need to know what is happening in advance, to have their expectations set and to be kept constantly informed and updated and, in The Queue, they have had that.

Perceived fairness is also important, with VIP lanes visually separate so it does not appear someone has just turned up and walked straight through.

"So long as people know what's happening, what's expected of them, how long it's going to take, they no longer face the uncertainty," he says. "And it keeps the crowd very much on your side."

People are happy if they know what is happening, even if the update is to say the update is coming.

"It's as soon as that information flow stops that you get a degree of uncertainty and people start behaving as individuals rather than as a collective," he says.

The Queue's temporary closure on Friday afternoon briefly concerned him. People were already on their way to join the end. "When they announced that the queue had stopped I thought 'you're just going to create another queue of people waiting to join the queue'," he says.

But this was "already in the contingency plan" and the closure was quickly reconsidered and The Queue extended out beyond Bermondsey.

The longer the queue, the more facilities you need to provide. As well as information, the crowd needs toilets, food, drinks, shelter and medical care.

"Eight hours might be acceptable for most people but 10, 12 - where's the limit of human endurance when standing for that length of time? These are all factored in," Prof Still says.

PA Media

PA MediaHe does not think he could have stood for that length of time himself, not with arthritic hips. "At 63, I can walk my dog for about 4km and that's it, I'm knackered for the rest of the day," he says.

But he trusts The Queue and has faith in the handful of his Masters students from Manchester Metropolitan University who took over from him in the team managing its planning.

These things are "always a significant team effort", he says.

"It's never just one person."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].