The black arts movement reflecting society today

David Mensah / BCA

David Mensah / BCAWolverhampton in 1979. Let's paint the canvas.

A little over a decade on from Enoch Powell's infamous Rivers of Blood speech, a group of black students met at the art school at Wolverhampton Polytechnic to discuss life, youth and art, in all its guises.

They were drawn together at a tumultuous time for the city and against the grey skies of persistent protest.

There were public marches opposing the National Front and rallies to highlight incidents of alleged police brutality towards minority groups.

Young black men and women felt squeezed from society and unable to find a voice, artistically or otherwise.

And these young artisans included the sons and daughters of the Windrush generation, who had arrived in Wolverhampton before the 1971 Immigration Act, when Commonwealth citizens already living in the UK were given indefinite leave to remain.

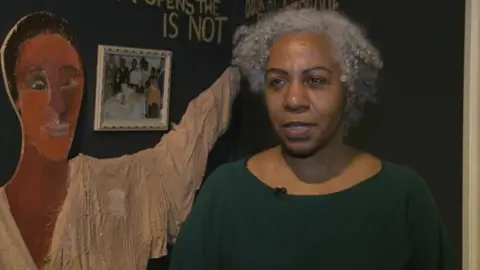

Marlene Smith

Marlene SmithClaudette Johnson, Eddie Chambers, Keith Piper, Marlene Smith, Donald Rodney and Janet Vernon are the among original members of the BLK art group and together they found a voice to counter the narrative and societal discourse.

Thursday 28 October 1982 is a date etched in their minds. It was the first National Black Art Convention whose purpose, according to Mr Piper, was to discuss "the form, function and future of black art".

"If you can imagine being in an arts college in the 1980s, there weren't that many black students and it felt like an urgent need to take on issues like race," said Ms Smith.

The movement attracted the likes of Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid; recipient of the Venice Biennale 2022 Golden Lion Sonia Boyce; internationally renowned abstract artist Sir Frank Bowling; and acclaimed filmmaker Sir John Akomfrah, who will represent Great Britain in Venice at the 60th International Art Exhibition in 2024.

Mr Rodney died in 1998 after suffering with sickle cell disease. He was considered a pioneer of art that was political, challenging, innovative and smart.

The other BLK art group founder members say they're proud and delighted to have been given the opportunity to inspire a new generation of black artists, with The More Things Change, a new exhibition of their work and legacy at Wolverhampton Art Gallery, which runs until 9 July.

More than 30 works are on show including paintings, works on paper, mixed media, sculpture and film.

"It's like going into a room with old friends", says Ms Smith. "It's very insightful work, it's very demanding work and its message was really to get people to think about what race meant in the 1980s, and I think it still resonates today because we still don't have an open conversation about what race really means."

Ms Vernon was a fine art student and vice-chair of the first national convention in 1982.

Today, the textile specialist creates bold statement jewellery from her home in Derby, making patterns of patina on metals, drawing inspiration from urban landscapes.

"It was kind of amazing, the artists that I met on the foundation course. Our parents were from the Windrush generation and that was our initial connection. We were saying, 'we are here - we are not going to be invisible'."

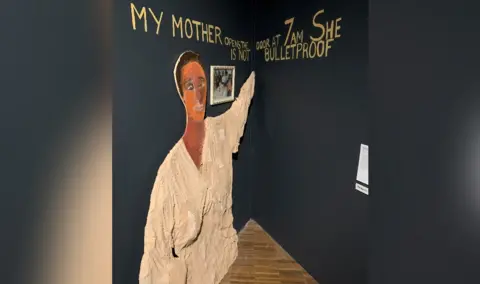

Two new commissions by Claudette Johnson and Marlene Smith are reworkings of their seminal works, And I Have My Own Business In This Skin (1982) and Good Housekeeping (1985). Back on public display in Wolverhampton, back home.

Dr Sylvia Theuri, the co-curator of The More Things Change, says the materials the artists used were also really important.

"The political element and undertone to the work has been discussed for a long time, but they are also distinctive artists in their own right, developing a practice with materials that really allow an audience to understand what they were trying to communicate. All artists are drawing from lived experience."

Last autumn, on the 40th anniversary of their first convention, dozens of artists who enriched Britain's first black arts movement met to celebrate their work and honour those pioneers who influenced their artistry.

And for student Chandni Raithatha, 20, the impact of their work continues. She moved from London to study photography at the University of Wolverhampton after reading about the history of BLK art group at the Tate gallery.

She has joined a new collective called Togetherness at Wolverhampton's art school and has her own digital images, including The Black Prince exhibited at the city's art gallery this year.

Chandni Raithatha

Chandni Raithatha"I want people to see my work, to question the themes. It's really empowering to see black artists - to see people like you sharing their voice - is really inspiring. The themes they were focusing on are still relevant today."

The BLK art group had felt like outsiders against a backdrop of the rise of Thatcherism and dissenting voices in their own neighbourhoods.

But by 1984 they were anything but a group of individuals - instead seen as international collective who knew no bounds and no fear.

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: [email protected]