Coronavirus: Ministers consider NHS contact-tracing app rethink

BBC

BBCConcerns about the risks of deploying a go-it-alone UK coronavirus contact-tracing app are causing further delays.

A second version of the smartphone software was due to have begun testing on the Isle of Wight on Tuesday, but the government decided to postpone the trial.

Ministers are considering switching the app over to tech developed by Apple and Google.

But countries testing that model are experiencing issues of their own.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock had originally said the NHS Covid-19 app was to be launched across England - and possibly other parts of the UK - by 1 June.

But he subsequently said the government had decided it would be better to establish a network of human contact tracers first.

However, the BBC has discovered that one of the main reasons the initiative is running behind schedule is that developers are having problems using Bluetooth as a means to estimate distance.

PA Media

PA MediaEven so, they still believe they are better placed to tackle the challenge than counterparts overseas who are working under constraints imposed by the two US tech firms.

Bluetooth handshakes

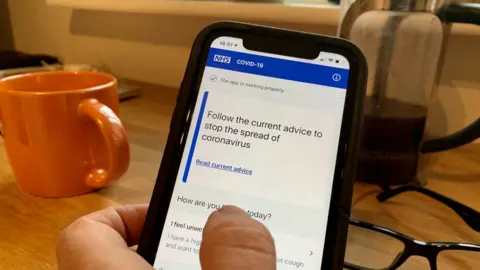

Contact-tracing apps are designed to prevent a second wave of infections by keeping a log of when two people are in close proximity to each other and for how long.

If one of the users later tests positive for the disease, the records are used to determine how likely it is they infected the other. If required, an alert is triggered to help prevent the further spread of the virus.

The UK has adopted what is known as a "centralised" approach, meaning that the contact-matching process is carried out on a remote computer server. One benefit is it offers epidemiologists more data to tackle the pandemic. France and India are other countries to have adopted this model.

By contrast, Apple and Google's "decentralised" approach carries out the matches on the handsets themselves, on the grounds this better protects users' privacy.

Poland switched its app from a centralised to decentralised approach on Tuesday. Switzerland, Ireland, Germany, Italy and Latvia are among others to have adopted the tech giants' design.

Both systems rely on Bluetooth "handshakes" to work.

Number 10 is concerned that iPhones will not always detect each other because of a restriction Apple has imposed on apps that do not adopt its model.

But the UK team has devised a workaround and is more concerned about other limitations of using Bluetooth.

Train trouble

Some of these issues were outlined in a study published by Trinity College Dublin last month.

It highlighted problems with using received Bluetooth signal strength as a means to estimate distance.

Researchers warned signal strength "can vary substantially" depending on:

- how deeply a handset is placed in a bag

- whether the signal has to pass through a human body to reach the other phone

- if the two people are walking side-by-side or one behind the other

- if the devices are indoors rather than outdoors

- whether the smartphone is surrounded by metal objects

The report highlighted troubling results when Singapore's TraceTogether app was tested.

PA Media

PA MediaAn experiment within a stationary train carriage found that when users moved from a distance of 3.5m (11.5ft) to 4m, signals became stronger rather than weaker because of the way metal objects were reflecting the radio waves.

A trial in a supermarket also found the received signal strength was the same whether two people were walking close together or 2m apart.

Follow-up tests using Apple-Google's tech are currently under way.

"The work is ongoing, but preliminary results are broadly consistent with previous observations," said Dr Brendan Jennings, who has been tasked with assessing the effectiveness of Ireland's Covid-19 app.

Hidden data

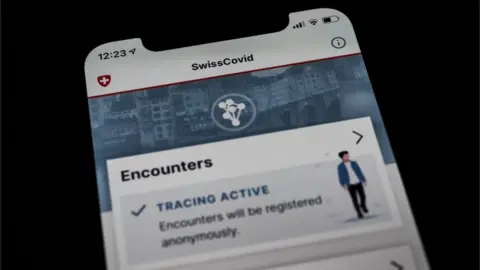

The team behind Switzerland's SwissCovid app is carrying out tests of its own.

Its Bluetooth measurement chief believes the issue can be partly addressed by taking a range of readings over a period of five minutes or more.

But he added that Apple and Google had placed curbs on what could be achieved.

"The Google and Apple API [application programming interface] limits the amount of raw information that is actually exposed to the app," Prof Mathias Payer told the BBC.

"For maximum utility, we would get all the different measurements, but this has privacy implications."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesApps using Google and Apple's tech do not get to see the actual signal strength but rather one of three values, based on calculations used to normalise the different ways Bluetooth behaves on different handsets,

By contrast, the UK team can currently obtain the measurements directly.

Those responsible believe a further advantage of their centralised approach is that the data can be processed on the server involved, since it would be too taxing a task to be done on smartphones.

But part of their challenge is communicating this to Baroness Dido Harding - who heads up the wider Test and Trace programme - and 10 Downing Street itself.

A spokesman for the prime minister declined to comment.