The Gypsy mayor who wants Gypsies to mix with everyone else

Mahka Eslami

Mahka EslamiFrance has about half a million Gypsies but only one Gypsy mayor - and curiously, he is more popular with non-gypsy constituents than with his own people. Chris Bockman found out why.

The view is amazing: the imposing and well-preserved medieval towers of the citadel town of Carcassonne, set against the backdrop of the Black Mountains. It looks almost fake, like a film set.

This place gets more than two million visitors a year - but you won't find the spot where I'm standing on anyone's tourist map and most local people go out of their way to avoid it.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBehind me is a grim, concrete electrical sub-station and beyond that a neighbourhood with the totally inappropriate name of Cite d'esperance - meaning roughly "Estate of Hope".

It's made up of ramshackle homes put together from caravans, cinder blocks or metal sheets, linked by muddy, unpaved roads. Wrecked cars and other debris litter the gardens or common spaces. Sad-looking dogs are tied up or penned in.

This is home to 300 travellers - a Gypsy community, described in French as Gitans or gens de voyage. Most of those here have roots in northern Spain and are distinct from the Gypsy communities of northern France, which originated in Germany and Eastern Europe and are referred to as Roma. The southern Gypsies speak Catalan at home, even though they have lived in France for generations.

BBC

BBCThe Cite d'Esperance is part of the village of Berriac - with a population of just over 1,100 - and I've come here to meet France's only elected Gypsy mayor, Michel Soules.

He's 57 years old with a tanned, lived-in face, a strong southern accent and a flamenco music ring tone on his mobile phone. We get talking about his background - and why, contrary to what you might expect, many of his Gypsy constituents are against him.

Michel was born in 1961 next to an illegal rubbish dump, one of 10 children. He was married off by his mother at the age of 16 to a girl he had never met before. He says he stayed married to her for 17 years and raised four children, only discovering real love after his divorce at the age of 38. Marrying outside the traveller community was once taboo, he tells me, but now it's more accepted.

- From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

- Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 and Thursdays at 11:00

The mairie or village hall is in Berriac's historic district, far from the Gypsy homes. Michel became mayor here almost by accident. He was a local librarian and councillor when the longstanding incumbent died. He was asked to fill in until the next elections, in 2014, which he then won with 70% of the vote.

But he didn't win thanks to the traveller community - rather in spite of it. He made no secret of his plan to close down the Estate of Hope, and relocate its residents. They need to integrate with the rest of French society, he argues, in order to break the cycle of poverty most are trapped in.

Among residents of the estate, this is an unpopular view.

In the middle of it, there's a community centre run by the regional council. Bruno Ardouin, who works there, tells me that most of the residents need help filling out documents to claim state benefits, replying to court orders or dealing with final demands for utility payments. He says nearly half the Gypsies in Berriac don't know how to read or write and many of the children drop out of school before they turn 16.

Mahka Eslami

Mahka EslamiAll too often, what follows is the usual cycle of crime and prison. According to the mayor, the only solution is to stop generous benefits and physically break up the community.

Some of the travellers with full-time jobs or greater aspirations have already moved away. Most of those left behind are opposed to the mayor's plans, and he's not well received as we wander through the estate. On a weekday afternoon, there are plenty of men sitting around in cars, smoking or drinking.

We talk to Sylvain, who isn't a traveller himself but married into a gypsy family. His relatives and their friends have the traveller blood still in them, even if they don't move around any more - and he says that means they're culturally resistant to change and regulations. They don't like anything being imposed from above by the authorities.

Next year three gypsy homes will be demolished and residents moved into new public housing closer to the centre of the village. Before the mayor is finished, the residents of another 19 homes will have followed them.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe is now in demand in other towns with large gypsy communities, such as Perpignan on the Mediterranean coast, to offer advice on how to break their social isolation.

But he hasn't decided yet whether to run for re-election next year. He says the job is draining - he's caught between the traveller community, who accuse him of selling out, and the rest of the village, who blame gypsies for creating an atmosphere of insecurity. Some don't want them moving any closer.

Berriac, like many villages and towns around here, voted overwhelmingly for the far-right National Front's candidate in the 2017 presidential contest - which makes Michel Soules' position as mayor that much more remarkable, and a sign of hope in a divided community.

Chris Bockman is the author of Are you the foie gras correspondent? Another slow news day in south-west France

You may also be interested in:

BBC

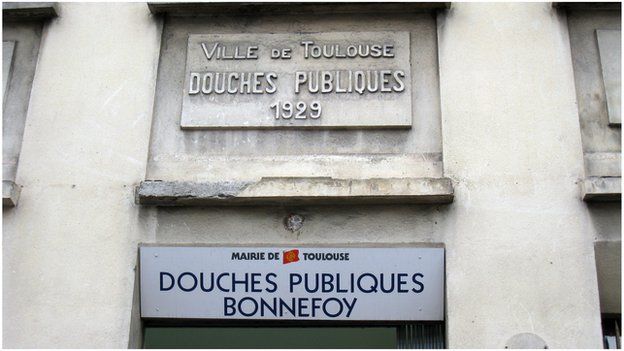

BBCThe number of public showers in France may be dwindling but in Toulouse, they still provide a vital public service - especially for those who've fallen on hard times.