Antarctica: Thousands of emperor penguin chicks wiped out

Christopher Walton

Christopher Walton

Thousands of emperor penguin chicks drowned when the sea-ice on which they were being raised was destroyed in severe weather.

The catastrophe occurred in 2016 in Antarctica's Weddell Sea.

Scientists say the colony at the edge of the Brunt Ice Shelf has collapsed with adult birds showing no sign of trying to re-establish the population.

And it would probably be pointless for them to try as a giant iceberg is about to disrupt the site.

The dramatic loss of the young emperor birds is reported by a team from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

Drs Peter Fretwell and Phil Trathan noticed the disappearance of the so-called Halley Bay colony in satellite pictures.

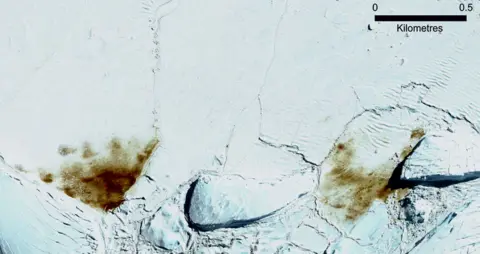

It is possible even from 800km up to spot the animals' excrement, or guano, on the white ice and then to estimate the likely size of any gathering.

But the Brunt population, which had sustained an average of 14,000 to 25,000 breeding pairs for several decades (5-9% of the global population), essentially disappeared overnight.

DigitalGlobe, a Maxar company

DigitalGlobe, a Maxar companyEmperors are the tallest and heaviest of the penguin species and need reliable patches of sea-ice on which to breed, and this icy platform must persist from April, when the birds arrive, until December, when their chicks fledge.

If the sea-ice breaks up too early, the young birds will not have the right feathers to start swimming.

This appears to have been what happened in 2016.

Strong winds hollowed out the sea-ice that had stuck hard to the side of the thicker Brunt shelf in its creeks, and never properly reformed. Not in 2017, nor in 2018.

Dr Fretwell said: "The sea-ice that's formed since 2016 hasn't been as strong. Storm events that occur in October and November will now blow it out early. So there's been some sort of regime change. Sea-ice that was previously stable and reliable is now just untenable."

The BAS team believes many adults have either avoided breeding in these later years or moved to new breeding sites across the Weddell Sea. A colony some 50km away, close to the Dawson-Lambton Glacier, has seen a big rise in its numbers.

You may also be interested in:

Quite why the sea-ice platform on the edge of the Brunt shelf has failed to regenerate is unclear. There is no obvious climate signal to point to in this case; atmospheric and ocean observations in the vicinity of the Brunt reveal little in the way of change.

But the sensitivity of this colony to shifting sea-ice trends does illustrate, says the team, the impact that future warming in Antarctica could have on emperor penguins in particular.

Research suggests the species might lose anywhere between 50% and 70% of its global population by the end of this century, if sea-ice is reduced to the extent that computer models envisage.

This would have consequences beyond just the emperors themselves, commented Dr Michelle LaRue, an ecologist at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand.

"They're an important part of the food web; they're what we call a mesopredator. They're both prey for animals like leopard seals but they also prey themselves on fish and krill species. So, they do play an important role in the ecosystem," she told BBC News.

DigitalGlobe, a Maxar company

DigitalGlobe, a Maxar companyDr Trathan said: "What's interesting for me is not that colonies move or that we can have major breeding failures - we know that. It's that we are talking here about the deep embayment of the Weddell Sea, which is potentially one of the climate change refugia for those cold-adapted species like emperor penguins.

"And so if we see major disturbances in these refugia - where we haven't previously seen changes in 60 years - that's an important signal."

Whether the Halley Bay colony specifically really had a future is a moot point.

The Brunt Ice Shelf is being split apart by a developing crack.

This chasm will eventually calve an iceberg the size of Greater London into the Weddell Sea, and any sea-ice stuck to the berg's edge may break up in the process.

The colony could have been doomed regardless of what happened in 2016.

Drs Peter Fretwell and Phil Trathan report their investigation in the journal Antarctic Science.

Christopher Walton

Christopher Walton

[email protected] and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos