Frog evolution linked to dinosaur asteroid strike

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYThe huge diversity of frogs we see today is mainly a consequence of the asteroid strike that killed off the dinosaurs, a study suggests.

A new analysis shows that frog populations exploded after the extinction event 66 million years ago.

It would appear to contradict earlier evidence suggesting a much more ancient origin for many key frog groups.

The work by a US-Chinese team of researchers is outlined in the journal PNAS.

Frogs became one of the most diverse groups of vertebrates, with more than 6,700 described species. But a lack of genetic data has hampered efforts to trace their evolutionary history.

The new study shows that three major lineages of modern frogs - which together comprise about 88% of living frog species - appeared almost simultaneously.

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

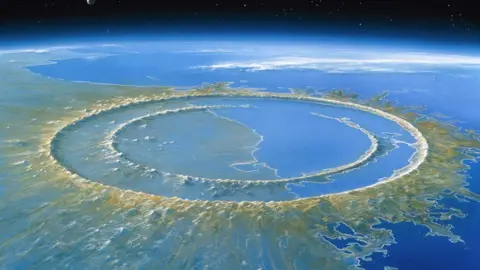

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYThis impressive diversification of species appears to have occurred on the heels of the asteroid, which struck what is now the edge of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

Releasing upwards of a billion times more energy than an atom bomb, the space impact wiped out three-quarters of all life on Earth. But it also appears to have set the stage for the rise of frogs.

The scientists sampled a core set of 95 genes from the DNA of 156 frog species.

They then combined this data with genetic information from an additional 145 species to produce a detailed "family tree" of frogs, based on their genetic relationships.

Using frog fossils to provide "ground truth" for the genetic data, the researchers were able to add a timeline to their family tree. The three biggest frog groups - the hyloidea, microhylidae and the natatanura - all trace their origins to an expansion that occurred after 66 million years ago.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo Library"Nobody had seen this result before," said co-author Peng Zhang, from Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou, China.

"We re-did the analysis using different parameter settings, but the result remained the same. I realised the signal was very strong in our data. What I saw could not be a false thing."

Another author, David Blackburn, from the Florida Museum of Natural History, explained: "Frogs have been around for well over 200 million years, but this study shows it wasn't until the extinction of the dinosaurs that we had this burst of frog diversity that resulted in the vast majority of frogs we see today."

Dr Blackburn said the speed at which frogs diversified after the impact suggests that the survivors were probably filling up new ecological niches.

The Chicxulub event would have destroyed a large proportion of the vegetation on Earth. But as forests began to recover after the event, frogs seem to have been one of the groups that made the most of the new habitats.

The researchers point out that none of the frog lineages that originate before the extinction and survive through the asteroid impact happen to be adapted to living in trees.

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY"All origins of arboreality (e.g. within hyloids or natatanurans) follow the [Chicxulub extinction event]," the authors write in their PNAS paper.

This, they argue "supports the hypothesis that the [Chicxulub] mass extinction shaped the current diversity of frogs".

The study also indicates that global frog distribution tracks the break-up of the supercontinents, beginning with Pangaea about 200 million years ago and then Gondwana, which split into South America and Africa.

The data suggests frogs likely used Antarctica, not yet encased in ice sheets, as a stepping stone from South America to Australia.

"I think the most exciting thing about our study is that we show that frogs are such a strong animal group. They survived... the mass extinction that completely erased dinosaurs," said Peng Zhang.

However, frogs - like other amphibians - face many challenges today, including habitat loss due to logging and diseases such as the chytrid fungus and ranavirus.