Climate change: Do I need to stop eating meat?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlmost a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions comes from agriculture and other related land use, according to the United Nations.

With livestock being one of the main contributors, the government's climate advisers have said the public should be urged to less meat to help protect the planet.

How much meat do we eat?

Meat consumption in the UK dropped by 17% in the decade to 2019, with the average daily amount eaten per person falling from from 3.6oz (103g) to 3oz.

But while most people are eating less red and processed meat compared to a decade ago, they are eating more white meat, according to a study published in Lancet Planetary Health.

More than one billion chickens and other poultry were killed for food in the UK in 2018.

What impact does meat have on emissions

The impact of livestock on emissions varies between countries. Globally, the UN estimates it makes up more than 14% of all man-made greenhouse gases, including methane.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen we talk about emissions, we usually think of carbon dioxide (CO2). But livestock's emissions also include methane, which is up to 34 times more damaging to the environment over 100 years than CO2, according to the UN.

Beef produces the most greenhouse gas emissions, which include methane. A global average of 110lb (50kg) of greenhouse gases is released per 3.5oz of protein.

Lamb has the next highest environmental footprint but these emissions are 50% less than beef.

Cattle produce more methane than poultry, which rely more on imported feed than cows, generating a carbon footprint offshore, says Prof Margaret Gill, from University of Aberdeen.

How do you measure emissions from meat?

Measuring and comparing the environmental impact of different foods is not simple.

This is partly because some measurements include emissions from processing, packaging and transportation, rather than just the farming process.

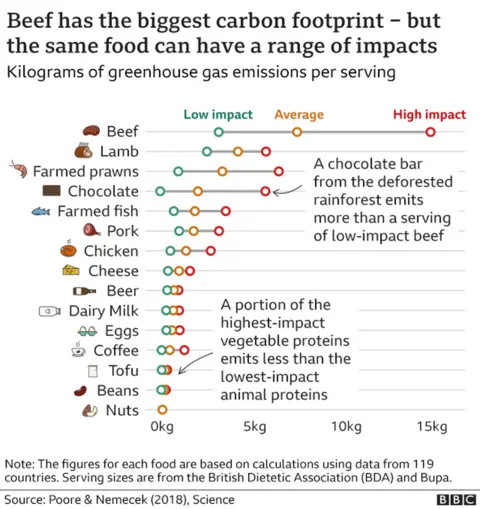

The diagram below is based on research published in the Science journal, which estimated emissions per serving of different foods. It shows a wide range of potential environmental impact, even within the same foods, depending on how and where they are produced.

According to the UK's Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, greenhouse gas emissions are lower from UK-produced beef, partly because the "landscape and climate is perfect for growing grass, with grasslands covering 65% of our farmland and 50% of total land". This means cows don't rely as much on grain and other feed, which can have a high carbon footprint.

Other factors around the world vary the environmental impact. Beef production is the leading cause of deforestation in tropical rainforests such as the Amazon, says food sustainability researcher Valentina Caldart. This adds to the environmental impact of beef from that part of the world.

So, what can you do?

The true climate impact of what we eat is not easy to calculate, says Prof Gill. "Carbon footprints of food vary with how it is produced and where it comes from, and thus changes with the seasons," she says.

So, as well as cutting down on red meat and dairy, people who want to make their diets more climate-friendly can follow principles including minimising waste and trying to choose fruit and vegetables that are in season.

Prof Gill says there is: "A need for transition - albeit fairly rapid - rather than abrupt change."

What about other foods?

Many people wanting to reduce the environmental impact of their diets have cut out animal products such as milk and cheese. According to the Vegan Society, there were 600,000 vegans in the UK in 2018.

The biggest environmental impact of non-meat products comes from land use change, the effect on soil quality and things like transport and packaging.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNon-animal protein generally emits much less greenhouse gases than meat and dairy.

"Replacing beef with pork may sound like a good choice," says Ms Caldart. "But opting for peas instead would be even better: their production results in 90% less emissions."

What is the wider impact of what we eat?

How we produce our food does not just affect our global emissions, but has a wider environmental impact, such as on biodiversity.

"We live on a planet where nature is being squeezed out" says Mike Barrett, executive director of science and conservation at the World Wildlife Fund.

"Half of all habitable land is used for agriculture, and three-quarters of that land is used to feed and raise livestock."

Mr Barrett says: "To feed a growing world population, it's far more efficient to use land to produce crops that people can consume directly, and to have a fair global approach ensuring that parts of the world with diets high in meat and dairy shift towards more plant-based foods."

Adopting a "flexitarian" diet would also allow us to move away from factory farming with its low animal welfare standards, says Peter Stevenson, chief policy adviser to the charity Compassion in World Farming.