What are negative interest rates?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Bank of England has taken another step towards adding negative interest rates to its crisis-fighting toolbox.

It's given High Street banks six months to be operationally ready for them.

Policymakers stressed that this did not mean that sub-zero borrowing costs were "imminent, or indeed in prospect".

But what exactly are negative interest rates? And could a world where savers are penalised and borrowers rewarded end up doing more harm than good?

What are negative interest rates?

The term "interest rates" is often used interchangeably with the Bank of England base rate.

Described as the "single most important interest rate in the UK", the base rate determines how much interest the Bank of England pays to financial institutions that hold money with it, and what it charges them to borrow.

High street banks also use it to determine how much interest they pay to savers, as well as what they charge people who take out a loan or mortgage.

The Bank of England usually lowers interest rates when it wants people to spend more and save less.

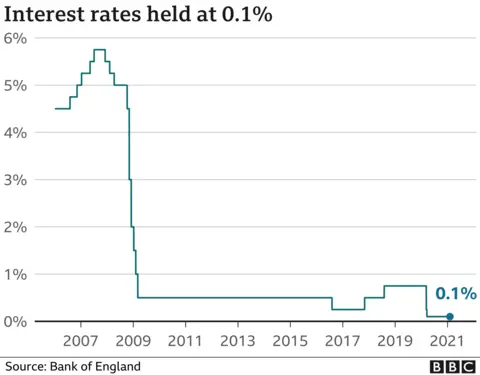

It cut them to a fresh low of 0.1% in March 2020 to try to stimulate the economy amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn theory, taking interest rates below zero should have the same effect. But in practice, it's a bit more complicated.

After all, why would anyone pay to stash money in a savings account or lend someone money, when they can keep the cash at home for free?

Why might this happen now?

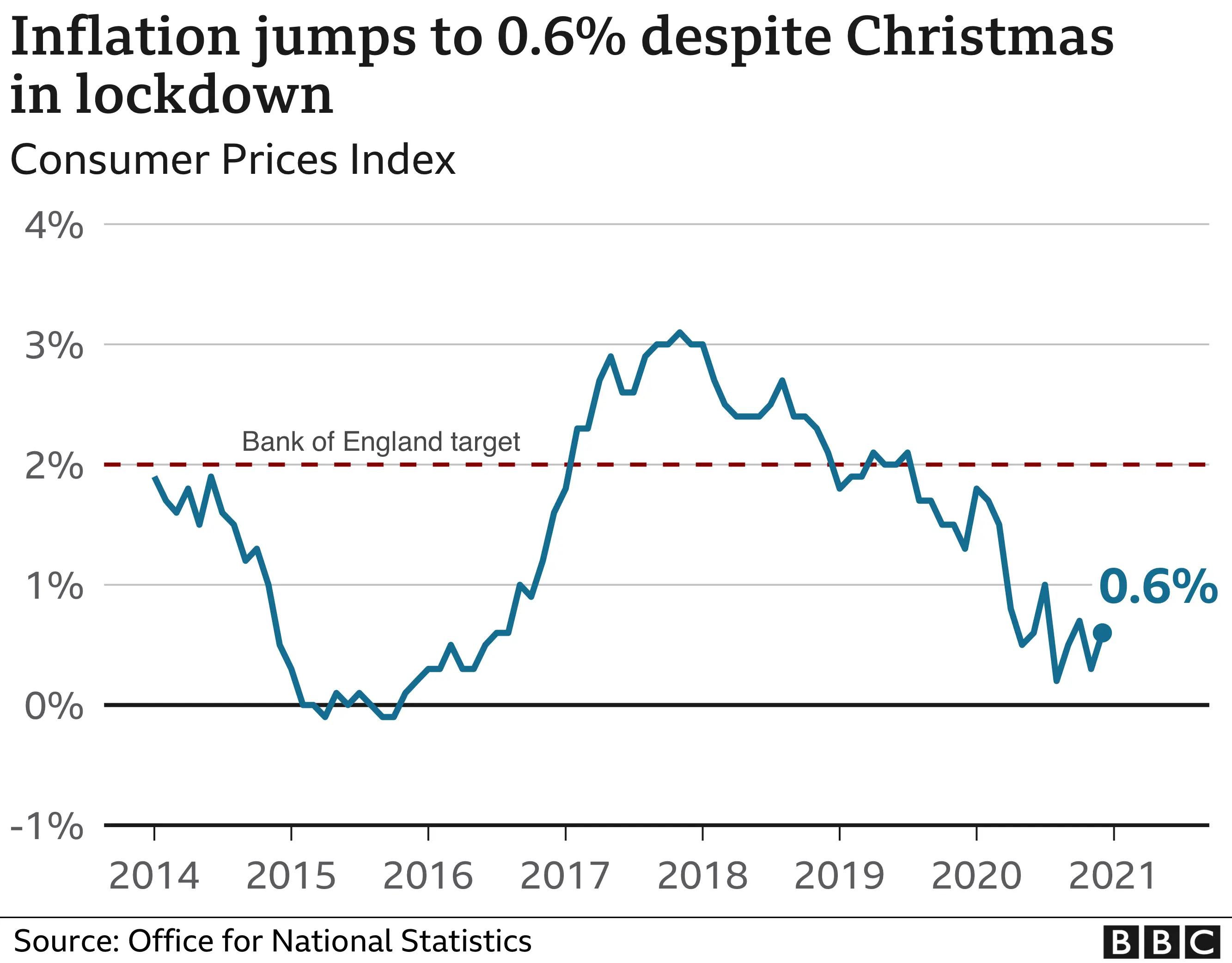

The Bank of England's number one job is to keep prices across the economy rising steadily every year.

This is known as the Bank's inflation target, which is set at 2% by the government.

Inflation measures how quickly the cost of living is rising.

And, measured by the consumer prices index (CPI), it stood at 0.6% in December, up from 0.3% in November 2020.

While low inflation means prices aren't rising quickly, if it remains low for too long, bosses start factoring that into pay reviews.

This can then dampen consumer confidence and spending.

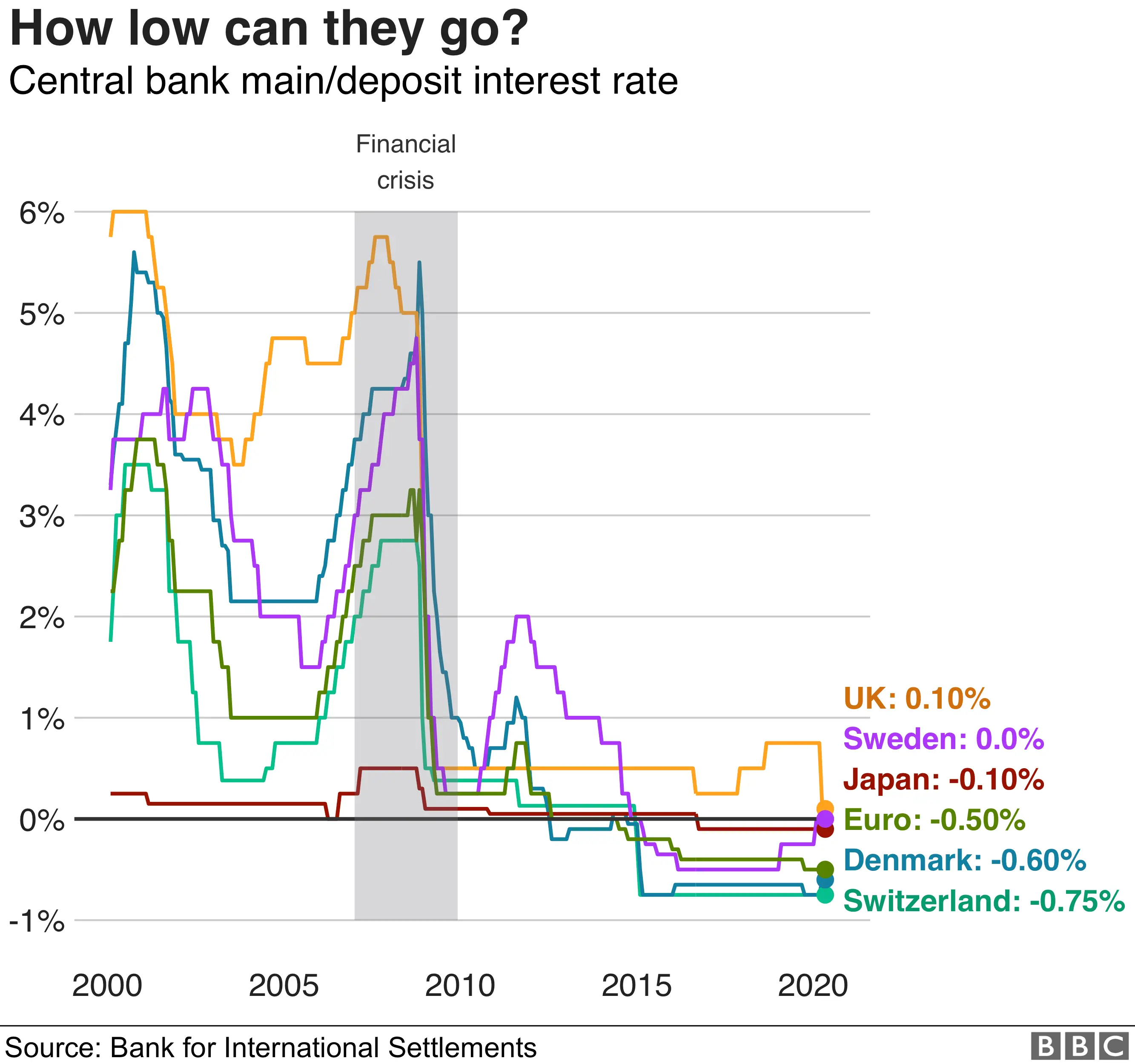

Central banks have been cutting interest rates to spur inflation for years. But as rates approached zero across the developed world, a handful went a step further.

Sweden, Switzerland, Japan and the 19 nations of the eurozone all took interest rates below zero.

In Switzerland, negative interest rates have also helped to discourage investors from pouring money into the country during times of uncertainty.

How will this affect savers?

British savers have already seen their returns dwindle in recent years.

The average UK instant access account pays just 0.12%, according to the Bank of England, while accounts that require you to lock your money away currently offer an average return of 0.51%.

In countries with sub-zero interest rates, commercial banks have passed them on to big companies.

However, the evidence suggests there is a very high bar to pass the pain on to ordinary savers.

Christina Nyman, chief economist at Swedish lender Handelsbanken, says charging savers to put money in their own accounts is seen as "taboo" in Sweden.

She says: "Competition is fierce, and households are ready to move their money to another bank, so nobody wants to lose business."

Swiss banks UBS and Credit Suisse only impose negative rates on deposits of more than 2 million Swiss francs.

In Germany, where some banks impose charges on deposits of more than €100,000 (£90,000), some people have started stashing their money in vaults.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to Germany's central bank, physical cash holdings by families and businesses there have almost trebled to €43.4bn since the European Central Bank (ECB) introduced a negative deposit rate in 2014.

But David Oxley at Capital Economics says there hasn't been a wider shift towards cash because most people still prefer the security and convenience of keeping it in the bank.

Putting it in a vault "runs the risk of the money either being lost, stolen, or damaged," he says. "Bank deposits cannot catch fire, but banknotes can."

What about borrowers?

Negative rate mortgages already exist. In 2019, Danish bank Jyske announced that it would effectively pay borrowers 0.5% a year to take out a 10-year loan.

James Pomeroy, an economist at HSBC, says this was only possible because of the nature of the mortgage market.

When someone in Denmark applies for a home loan, Danish banks act as a middleman between potential borrowers and investors.

"In Denmark the banks don't take the hit, investors do," says Mr Pomeroy. "Banks are then charging higher product fees, so have actually made money off of this."

But negative rate mortgages are unlikely to be offered in the UK any time soon.

When UK interest rates were slashed to 0.5% in March 2009, some borrowers thought they could be in line for a payment.

Around 1,500 Cheltenham and Gloucester customers had a mortgage that tracked 1.01 percentage points below the Bank of England base rate.

But any prospect of a windfall was quickly dashed when financial regulators described interest payments as "a one-way obligation on the borrower".

Matt Cardy

Matt CardyIn a letter to UK bank bosses, Sam Woods, chief executive of the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), said some lenders would need up to 18 months to make permanent changes needed to deal with negative rates.

While "short-term fixes" could be implemented within six months, upgrading systems not built to deal with a negative Bank of England base rate would take longer, especially for some mortgage customers.

Banks said they would find it easier to explain and implement changes to big corporate clients, because many already had international experience with negative rates.

What are the side effects of negative interest rates?

Negative interest rates hit bank earnings by squeezing the gap between the money they make on loans and what they pay to savers.

"If not passed on to customers, negative rates would hurt bank profitability, especially at a time when they are expected to be hit by crisis-related loan losses," says Danae Kyriakopoulou, chief economist at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF).

Nationwide

NationwideNegative interest rates pose a particular challenge to building societies, which hold around £1 of every £5 in British savings accounts.

While commercial banks can access cheaper borrowing by tapping financial markets, building societies must raise at least half their funding from individual savers.