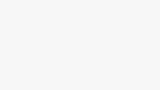

Who is Yoon Suk Yeol, South Korea's arrested president?

AFP

AFPSouth Korea's president Yook Suk Yeol has been arrested by anti-corruption investigators, following a weeks-long stand-off between investigators and his personal security detail.

The 64-year-old, who plunged South Korea into political turmoil with his short-lived martial law declaration on 3 December, is the first sitting president to be arrested.

Yoon's attempt at martial law led to his impeachment by parliament on 14 December, though a constitutional court still has to decide if his impeachment is final.

The Central Investigation Office for High-ranking Officials (CIO), also began investigating Yoon for insurrection -which is punishable by life in prison or death.

But Yoon refused to cooperate with the authorities, ignoring several summonses to come in for questioning. This led to the CIO applying for an arrest warrant to bring him in.

His arrest on 15 January came after a failed attempt 12 days before, which saw his supporters and the Presidential Security Service (PSS) block authorities from reaching him at his official residence in Seoul.

The successful attempt which saw the deployment of 1,000 officers from the police and CIO, was initially blocked by the PSS who erected barricades to stop investigators from entering.

In a three-minute video message released after his arrest, Yoon said that while he continued to oppose the inquiry against him, he agreed to appear before investigators to "prevent any unsavoury bloodshed".

But even before his martial law order, Yoon had already found himself in a political quagmire, plagued with personal scandals and mounting pressure from the opposition.

- How one man threw South Korea into a political crisis

- Why is it so hard to arrest South Korea's impeached president?

- The president's gamble backfired: What was he thinking?

- What is martial law and why was it declared?

- Woman who grabbed South Korean soldier's gun speaks to BBC

- How two hours of martial law chaos unfolded

Rise to power

Yoon was a relative newcomer to politics when he won the presidency. He had risen to national prominence for prosecuting the corruption case against disgraced former President Park Geun-hye in 2016.

In 2022, the political novice narrowly beat his liberal opponent Lee Jae-myung by less than 1% of the vote - the closest result the country has seen since direct elections started to be held in 1987.

At a time when South Korean society was grappling with widening divisions over gender issues, Yoon appealed to young male voters by running on an anti-feminism platform.

People had “high hopes” for Yoon when he was elected, said Don S Lee, associate professor of public administration at Sungkyunkwan University. “Those who voted for Yoon believed that a new government under Yoon will pursue such values as principle, transparency and efficiency.”

Yoon has also championed a hawkish stance on North Korea. The communist state was cited by Yoon when he tried to impose martial law.

He said he needed to protect against North Korean forces and “eliminate anti-state elements”, even though it was apparent from the outset that his announcement was less about the threat from the North and more about his domestic woes.

Yoon is known for gaffes, which haven’t helped his ratings. During his 2022 campaign he had to walk back a comment that authoritarian president Chun Doo-hwan, who declared martial law and was responsible for massacring protestors in 1980, had been "good at politics".

Later that year he was forced to deny insulting the US Congress in remarks made after meeting US President Joe Biden in New York.

He was caught on a hot mic and seen on camera seemingly calling US lawmakers a Korean word that can be translated as "idiots" or something much stronger. The footage quickly went viral in South Korea.

Still, Yoon has had some success in foreign policy, notably improving ties in his country's historically fraught relationship with Japan.

‘Political miscalculation’

Much of the scandal surrounding Yoon's presidency centred around his wife Kim Keon Hee, who was accused of corruption and influence peddling - most notably allegedly accepting a Dior bag from a pastor.

In November, Yoon apologised on behalf of his wife while rejecting calls for an investigation into her activities - a move that did little to help his wobbly approval ratings.

Yoon was relegated to a lame duck president after the opposition Democratic Party won the parliamentary election by a landslide last April. The result was widely seen as a vote of no confidence on Yoon's time in office.

Thereafter, Yoon was reduced to vetoing bills passed by the opposition.

"He used the presidential veto with unprecedented frequency," said Celeste Arrington, director of The George Washington University Institute for Korean Studies. "In terms of his ruling style, his critics called it authoritarian."

He also faced increasing pressure from his political opponents. In the lead-up to Yoon's martial law declaration, the opposition slashed the budget proposed by Yoon's ruling party and moved to impeach cabinet members for failing to investigate the first lady.

With such political challenges pushing his back against the wall, Yoon went for the nuclear option - a move that few, if any, could have predicted.

Dr Arrington said that many had worried about a political crisis "because of the confrontation between the president and the opposition-controlled National Assembly," said Dr Arrington. "Though few predicted such an extreme move as declaring martial law."

President Yoon's declaration of martial law was a "legal overreach and a political miscalculation", according to Leif-Eric Easley, professor of international studies at Ewha Womans University in Seoul.

"He sounded like a politician under siege," Dr Easley told the BBC. "With extremely low public support and without strong backing within his own party and administration, the president should have known how difficult it would be to implement his late-night decree."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAftermath

Crisis has engulfed Yoon's government in the wake of the martial law order, with top officials - including the ex-defence minister and heads of the police and military - being investigated for their involvement.

Divisions have solidified in the ruling PPP, which had teetered between defending the unpopular leader and denouncing him.

Yoon's impeachment vote passed in parliament with most PPP lawmakers opposing it. Party leader Han Dong-hoon, who had called for the removal of Yoon as the only way forward, resigned shortly after the vote as internal strife intensified.

Meanwhile, a stalemate persists in the opposition-dominated parliament.

Opposition lawmakers have already impeached Han Duck-soo, the prime minister who became acting president after Yoon. They accused Han of being Yoon's "puppet" after he vetoed opposition-led bills and refused to appoint three constitutional judges to oversee Yoon's impeachment trial.

And though finance minister Choi Sang-mok is in charge for now, the opposition has threatened to impeach him too.

Anger has swept the country, as massive crowds continually take to the streets calling for Yoon's impeachment. Yoon's supporters, however, are holding protests of their own.

Throughout the chaos, Yoon has projected what his critics see as defiance - or, as his supporters may see it, determination.

Following his arrest, Yoon expressed gratitude his supporters.

"Although these are dark days... the future of this country is hopeful," he said.

"To my fellow citizens, I wish you all the best and stay strong. Thank you."