Creating modern theatre in an ancient space

Adrian Fisher

Adrian FisherAs the sun sets over the Roman Theatre at Verulamium, audiences enjoying its latest summer season of productions will know that some 2,000 years previously, people were doing the same. But what is it like putting on modern theatre in an ancient space?

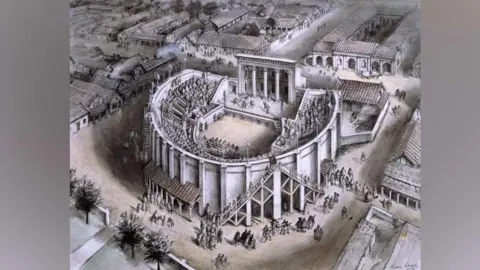

Built in about AD 140 in what was then the country's third-largest town, the theatre is thought to be the only example of its kind in Britain, having a stage rather than being an amphitheatre.

Sited just south-west of the modern city of St Albans, it was rediscovered in 1847 but not fully uncovered until the 1930s.

Since 2014, local theatre company OVO has produced the Roman Theatre Open Air Festival there every summer, but staging shows in such an important historic site leads to both challenges and delights.

St Albans Museums

St Albans Museums'You have to respect the site'

Alex Lee Johnson

Alex Lee JohnsonHead of production Mark O'Sullivan says there are "quite rightly, very strict rules about what can go where" but it is about "bringing live theatre to the audience in a way that also respects the archaeology and the history".

For example, the Romans put the stage in a place where the audience would have the sun on their backs, but the company has moved the stage to the opposite side to protect the foundations of the original performance area.

"We can't put anything into the ground, because we don't want to disturb any sort of archaeology that hasn't yet been discovered," he says.

"So it's about putting things on top of and around what's there in a way that protects them."

Katy Lewis/BBC

Katy Lewis/BBCHe says those who performed there nearly 2,000 years ago are never far from their thoughts and actors new to the venue are "almost always awestruck" by the legacy.

"There was one actor who was crying on the site one day, and I thought, 'Oh, no, what's happened?'" he says.

"But she was actually just moved by the idea of performing in this space that people like her had been working in 2,000 years before. It was a really beautiful moment.

"It's a real challenge [putting shows on], but when you get a fine evening, and people are sitting where people were enjoying theatre a couple of thousand years ago, there's nothing quite like it... it is a very special thing."

OVO

OVO'I feel privileged'

Katy Lewis/BBC

Katy Lewis/BBCThe festival's artistic director and founder, Adam Nichols, says it is an "incredible space" and he always feels "privileged" that the company performs there.

He says any constraints at the site "are often quite helpful".

"They force you to be creative, and to come up with innovative, interesting ways of presenting things that you might not have come up with if you had a completely free hand," he says.

For example, in its production of The Railway Children, a bridge sat between the grass mounds that would have been the theatre's original seating.

A cloth depicting a train was dropped over the front of the bridge to represent the train the children were trying to warn about a landslide.

Elliot Franks

Elliot FranksMoving the stage 180 degrees means that for about "half an hour on a bright evening" sunglasses needed for the audience but the company also finds the "stage just sits in the landscape better that way around", he says.

The venue is also now a big open space so performers need to be amplified, something their forebears would not have even had as an option.

"From what we know about the original theatre, the way the seating was configured would have created a sort of acoustic bowl and that would have given a lot of support to the performers vocally," he says.

"But we've got a very good sound system now.

"You definitely feel that sense of history and that sense of continuity…

"We're very conscious that when people come, they are there to see a great production, but also to experience that unique environment."

Katy Lewis/BBC

Katy Lewis/BBC'We are always careful where we are stepping'

Katy Lewis/BBC

Katy Lewis/BBCEmma Wright has performed at the festival every year since 2019 and this year is playing the dual role of Titania and Hipolyta in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

She says that because they cannot build a lot of backstage spaces, the audience and the actors are very aware of each other.

"It feels very intimate, which I love," she says, "and it feels very interactive, right from the get-go.

"You actually see everybody coming out in their costume and walking down through the audience to the stage."

Katy Lewis/BBC

Katy Lewis/BBCThe production crew do everything to make the site safe, she adds, and everybody is always mindful about where they are stepping.

"There are all sorts of bits that jut out and things might change from one year to the next, where something's kind of fallen down a little bit," she says.

"[We] obviously don't want injuries and they don't want any more stones dislodged.

"What is quite cool is that around the back you see a lot of oyster shells, where people would have been there in Roman times, watching whatever was going on and eating their oysters, so you sort of get constant little reminders of where you are.

"We're just there as guests of the space, which is lovely, actually. It feels quite an honour."

Adrian Fisher

Adrian FisherThe theatre is set within the Gorhambury Estate, which says it "takes a proactive approach to conservation".

It works with OVO to install protective matting during events, standalone staging structures, limitations on use to prevent ground damage, and constructing raised walkways to minimise erosion.

A spokesman says: "We are committed to maintaining a sensitive balance between cultural use and heritage protection, ensuring that this unique theatre continues to serve the community as both a historical treasure and a vibrant cultural venue."

The Roman Theatre Open Air Festival 2025 runs until 31 August.

Katy Lewis/BBC

Katy Lewis/BBCFollow Beds, Herts and Bucks news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.