Crushed weasel testicles and other medieval cures

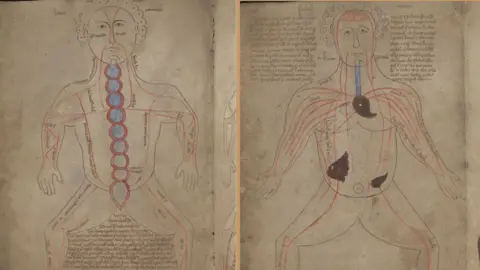

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, CambridgeDozens of unique, centuries-old manuscripts have gone on display, showcasing medieval ideas of how to cure disease and live a healthy life.

The cures include the use of crushed weasel testicles to help women conceive and mixing stewed apples with quicksilver (mercury) to rub on the body to destroy lice.

Dr James Freeman has supplied translations of their recipes next to the original manuscripts, as part of Cambridge University Library's Curious Cures exhibition.

He said visitors would learn about "medieval people trying to cure a bewildering array of illnesses and ailments, while operating within international networks of knowledge and study".

"It wasn't simply superstition or blind trial-and-error, it was guided by elaborate and sophisticated ideas about the body and the influence upon it of the wider world and even the cosmos," he added.

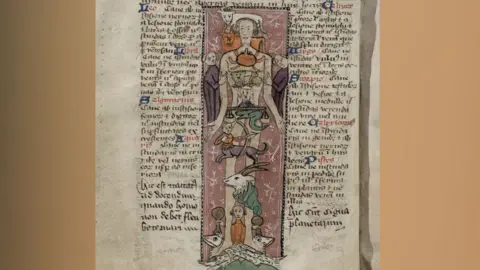

Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, CambridgeMedical understanding in the Middle Ages was underpinned by the idea of the "four humours".

Dr Freeman, the library's curator of medieval manuscripts, said: "The body contains four fluids - black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm, and when the four exist in balance you are healthy.

"But when they are out of balance, or corrupted, or concentrated in one part of the body where they shouldn't be, that causes disease."

It was the role of the physician to "understand your internal nature - look at your pulse and the colour, texture, smell and even the taste of your urine".

Once they understood that, they could tailor a treatment for their patients.

Amélie Deblauwe

Amélie DeblauweHowever, very few medical practitioners were university trained and most people relied on monks or friars, or barber-surgeons, apothecaries and herbalists, as well as home-based treatments.

So while many of the manuscripts are academic medical textbooks, Dr Freeman said: "Educated physicians were also copying down remedies that are very similar to ones we find in more popular or folk medicine compilations - the lines between learned and folk medicine is completely blurred."

One example is an apparently proven cure for nosebleeds.

Dr Freeman said: "The writer of a 15th Century compilation of medical remedies recommends dipping a man's testicles in cold water and vinegar - and if necessary, to repeat this process again.

"He says he has proved and tested it - and it worked on a friar in Stamford, Lincolnshire."

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, Cambridge"Bloodletting" was also a medieval practice, designed to purge the body of excess or imbalanced humours, and the blood would be drawn from different veins depending on the nature of the patient's illness.

"A further element to it was it ought to be done on accordance with particular astrological readings - if the moon is in conjunction with Aries, don't open a vein in the head, for example," Dr Freeman said.

"And far from being separate spheres - science, medicine and magic co-exist, so the exhibition shows a couple of manuscripts which have charms on them to harness divine or occult power."

How to prevent toothache, medieval-style

Richard Tenet, a Carmelite friar who probably studied at Oxford University, wrote about the following ritual:

- Repeat the Paternoster [Our Father] and Ave Maria [Hail Mary] while clipping your fingernails. At the fifth nail repeat the Credo [The Creed]

- Repeat with your other hand and both feet

- Wrap your clippings in a clean linen cloth and bury this in an elder tree

- You will be protected from toothache

In the manuscript, which is on display, Mr Tennant recounts how he learned the charm from a friar called John Lymington, who had learned it from an old woman.

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University LibrarySome of the medical advice included in a beautifully illustrated manuscript owned by Henry VIII's mother should sound familiar to modern ears.

Dr Freeman said: "Instead of looking at curing illness, Elizabeth of York's 15th Century copy of A Regime for the Body looks at maintaining and regulating your health - things like eat a balanced diet, get a good night's sleep, exercise and rest."

The manuscript was originally written in 1256 for Beatrice of Savoy, Countess of Provence, by her physician and includes chapters on courtship, sex, the care of pregnant women and how to care for a newborn baby.

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University LibraryWhich brings us back to why crushed weasel testicles might be considered to cure female infertility.

The recipe records they should be burned in a pot, combined with the juice of a plant called mouse-ear and the result placed inside a woman for three days.

"The likelihood is that there is some sort of sympathetic medical idea behind this - that this particular part of an animal cures the same part of the human body," said Dr Freeman.

"But there's no explanation given in the recipe, which is often the case with these sorts of treatments."

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, CambridgeFollow Cambridgeshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.