Does cutting benefits actually work?

BBC

BBCWork and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall has set out how the government plans to cut billions of pounds from the working-age welfare bill in the coming years.

The focus will be on reducing spending on health and disability benefits.

The bill is rising rapidly and many argue it needs to be curbed for the sake of the UK's public finances – as well as the economic and individual benefits of getting those who can work back into employment.

The plans include cutting the level of some benefits and tightening eligibility for others, along with investment to help people into work.

But this is not the first government to seek savings from the welfare budget.

BBC Verify has examined the past 15 years of policies in this area to see what might be effective – and what risks being counterproductive.

Cutting payments

The working-age health and disability benefits bill has certainly been increasing in recent years, and is rising rapidly.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the official forecaster, has projected that total state spending on these benefits for people in the UK aged between 18 and 64 will increase from £48.5bn in 2023-24 to £75.7bn in 2029-30.

That would represent an increase from 1.7% of the size of the UK economy to 2.2%.

By 2030, around half of the expenditure is projected to be on incapacity benefit, which is designed to provide additional income for people whose health limits their ability to work.

The other half is projected to be on Personal Independence Payments (PIP), which are intended to help people of working age with disabilities manage the additional day-to-day costs arising from their disability.

The government hopes to curb the rise in the overall bill by holding some of the benefits of existing incapacity claimants flat in cash terms - rather than allowing them to rise in line with inflation - until 2030.

It also plans to reduce the benefits of many new claimants outright relative to current levels.

This echoes the policies of previous governments.

Between 2014 and 2020, most working-age benefits were increased below the rate of inflation to save money.

This included a portion of the payments received by people on incapacity benefit.

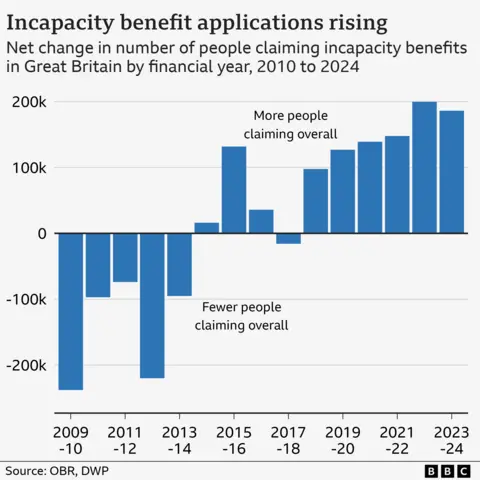

However, despite these real terms cuts in many benefits, from 2015, more and more people claimed incapacity benefit.

So cutting the value of individual payments might save some money up front, but still not have a dramatic impact on the overall bill in the longer term if claimants continue to rise.

Tighten eligibility

The Government is also planning to keep a lid on the overall working-age benefit bill by making it harder for people to claim some disability benefits, notably PIP.

This too echoes the policies of previous administrations.

For instance, Rishi Sunak's government had proposed making it harder for people with mental health conditions to claim PIP arguing that the monthly payment was not proportionate to the additional financial needs created by their conditions.

But it is important to note that efforts to change the eligibility criteria for these benefits over the past 15 years have not yielded the results hoped for.

PIP was introduced in 2013 to replace the old Disability Living Allowance, with the intention it would lead to savings of £1.4bn a year relative to the previous system by reducing the number of people eligible.

PIP was initially projected to reduce the number of claimants by 606,000 (28%) in total.

Yet the reform ended up saving only £100m a year by 2015, and the number of claimants rose by 100,000 (5%).

Another attempt in 2017 to limit access to PIP was also reversed.

The reason was that many people appealed against refusals that had been triggered by the tightened eligibility criteria.

Also, the emergence of cases in the media which seemed unfair meant ministers, often under pressure from their own backbench MPs, ultimately ordered the eligibility rules to be relaxed.

Official decisions not to award PIP and incapacity benefit to claimants are still often challenged and around two-thirds are ultimately decided in the challenger's favour at an independent tribunal.

Encourage work

The government is also seeking to make savings from the working age welfare bill by encouraging people to enter work.

Around 93% of incapacity benefit claimants are not in work and the same is true of 80% of PIP claimants.

One of the proposals is to have more regular reassessments of people on incapacity benefit to determine if their condition has changed and they can now be expected to work.

The fall in the number of people claiming incapacity benefit in the early 2010s has been attributed by the OBR to reassessments of a large number of people in receipt of an older form of the benefit.

However, an aggressive or onerous reassessment regime could risk imposing distress on people who are unable to work.

The government has said that those with "the most severe, life-long health conditions" will face no future reassessments. But it has not specified which conditions will qualify.

It has also set out plans to encourage more people on health and disability benefits into work through tailored and personalised support.

There have been various schemes designed to achieve this over the past 15 years, though they have not been on a large scale.

Evaluations have shown some positive employment effects from them.

However, the OBR concluded last year that the evidence base was still limited and did not suggest such programmes have, so far, made a "significant contribution" to getting people into work.

That implies the official forecaster may hesitate to assume greater state investment in these schemes will pay for itself through higher employment and tax revenues, and result in net savings in public expenditure.

Nevertheless, some experts argue it would make sense for the government to re-assess more regularly whether people in receipt of health and disability benefits are still unable to work and - if their circumstances are found to have changed - to provide them with additional support to get into the workforce.

"Not doing reassessments and work-focused interviews definitely makes things worse," says Jonathan Portes, a former chief economist at the Department for Work & Pensions.

Correction 17 March: an earlier version of this article wrongly stated the percentage of claimants' appeals upheld, based on DWP appeals. The article has been updated to reflect the full proportion, upheld at independent tribunal.