'What is our fault?': Families separated at India-Pakistan border

BBC Punjabi

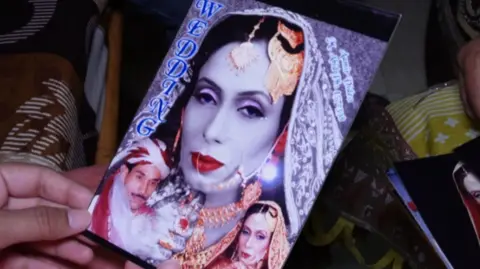

BBC PunjabiShahida's face crumpled with grief every time she thought about the choice in front of her: Stay for love or go back to her siblings?

Shahida Adrees, now 61, moved to India from Pakistan in 2002, when she married her maternal cousin Adrees Khan, a resident of Punjab state (marriage between cousins is practised in some communities in South Asia).

The couple lived a peaceful, predictable life - Khan working as a driver and Shahida looking after their home and child.

Every few years, Shahida, who is staying in India on a long-term visa, would obtain a travel permit and make a trip to Pakistan to meet her family.

But that sense of routine was shattered last week when India suspended almost all visas for Pakistani citizens as part of its response to the brutal attack in Indian-administered Kashmir that killed 26 people. Pakistan, which denies any involvement, has hit back with tit-for-tat measures and also cancelled most visas for Indians.

When Shahida heard the news, she knew what it meant; she could either go back to her siblings and other family members in Pakistan now, or stay and risk never seeing them again.

She chose to stay. Earlier this week, she cancelled her plans of going to Pakistan to see an ailing aunt. "If I had gone, I wouldn't have been let back into India. But now that I am here, I don't know if I'll ever see my brothers and sisters again," she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShahida's family is among hundreds in India and Pakistan who, with members on both sides of the borders, now face the risk of separation.

Despite neighbours India and Pakistan sharing a hostile relationship, love stories and marriages between its citizens are not uncommon. That's because of the deeply intertwined cultural history of the countries which were partitioned along religious lines in 1947, forcing millions to leave their homes and migrate to the other side.

The border between the nations runs not just through the ground, but also through families - many Indians have relatives and their hometowns in Pakistan, and vice versa.

Some, like Shahida's family, have tried to stay in touch with their roots through marriages with relatives across the border. In recent years, many couples have also met online, often overcoming insurmountable odds to stay together.

Many of them apply for long-term visas that need to be renewed periodically while others apply for citizenship of the respective countries - but the process can take years.

This week, as the visa restrictions took effect, heart-breaking visuals of people - young and old couples, desperate sons and daughters, and elderly parents - pleading with authorities for help were splashed across television screens and on social media.

The BBC has contacted the Indian foreign ministry for comment.

"I came here with my mother. Now they are asking us to leave without her. How can I do that?" mumbled a tearful Mohammed Ayat, 17.

A Pakistani national, Ayat came to India last month to meet his maternal relatives. His mother is an Indian citizen who was living in Pakistan on a visa that is pending renewal.

But even as her children returned to Pakistan, she had to stay in India as she wasn't sure whether she would be allowed into the country.

"They can punish them [the militants], but what is our fault?" Ayat told ANI news agency.

ANI

ANIThe exact number of people leaving both countries due to the latest tensions is not clear - but is estimated to run into hundreds.

Sitting in a bus that was taking her to the Attari-Wagah border, Parveen (who uses only one name), told reporters that she had lived in India for 41 years.

"I have no mother, brothers or sisters in Pakistan. I have nowhere to go there. I am completely helpless," she said.

Families say the abruptness of the visa suspensions and the resulting chaos have left them feeling uncertain.

The restrictions imposed by Delhi exempt those like Shahida, who have been living in India on a long-term visa which needs to be renewed every few years. Valid for up to five years, these visas are given to women of Pakistani and Bangladeshi nationalities who are married to Indian citizens.

Under Indian rules, all long-term visa holders are allowed to visit their home country after obtaining a second permit, called the No Objection to Return to India (NORI) visa.

But in the days following the attack, there have been reports of NORI visa holders also being stopped from crossing the border into India, as officials waited for clarity.

Shahida says that in her case, Indian authorities have assured her that NORI visa-holders would be exempted from the restrictions.

But she is not willing to take the risk of leaving India.

She wondered if things would've been better if she had got an Indian citizenship.

"I did apply for it in 2009, but the file never moved. I never received a response," she said.

For Tahira Ahmed, even becoming an Indian citizen has not been enough to allay her anxieties. A Pakistani by birth, Ms Ahmed moved to Punjab state in 2003 after marrying Maqbool Ahmed, an Indian . In 2016, Tahira was granted Indian citizenship, 13 years after her marriage.

But she is still fearful about the prospect of being separated from her family and sent to Pakistan.

Reuters

Reuters"Whenever tensions escalate between the two countries, our lives get caught up in the middle," she said. "My own wedding was postponed for two years in 2001 when the border was closed after an attack on India's parliament."

While they wait for answers, some couples are desperate.

Earlier this week, BBC Punjabi met Maria Masih, a Pakistani citizen who moved to India in 2024 to marry her lover Sonu.

The two met through social media and knew each other for many years before they decided to get married. According to Sonu, the couple applied for a long-term visa for Maria immediately after their wedding. But their application is still under process. Maria is now seven months pregnant.

"I want to live here. I don't want to go back. Please give me a visa and let me stay," a forlorn Maria told reporters earlier this week.

The couple has since reportedly been absconding and an investigation is under way.

Miles away, Ms Ahmed wonders if one can really blame them or anyone for trying to escape.

"What is their fault anyway? They came here for love," she said.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.