Torture or treatment? The rise of the mental asylum

Getty Images

Getty Images"One can hardly imagine a human being in a more degraded and brutalised condition than that in which I found this female."

These were the damning words of an inspector who visited London's Bethlem Royal Hospital in 1814 - better known by its notorious nickname, Bedlam.

And while such harrowing scenes had long been the norm, a quiet revolution in mental healthcare was already under way. It started not in the capital, but in Nottingham.

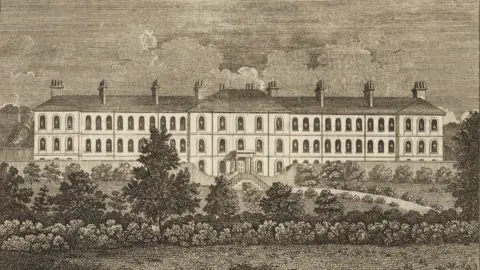

Now, new publishings into the groundbreaking Nottingham General Lunatic Asylum - the first publicly-funded asylum in England - has shone light into some of medical history's darkest corners.

When the institution opened in 1812, the asylum had already doubled its projected cost, with the final bill reaching £20,000 - an eye-watering sum for the era.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAuthor and researcher David Whitfield has drawn on his extensive study of the institution for his latest novel, The Unravelling of Mary Reddish, which brings to life the true story of a former patient.

He said: "It is very easy to look back and be shocked and appalled by the things that went on.

"But when you look at letters and speeches of the people who set Nottingham up, you get a different perspective."

It is unlikely to come as a surprise that the treatment of the mentally ill in earlier centuries was grim - but just how grim takes some believing.

Forced vomiting and diarrhoea, bleeding, blistering with hot irons, spinning and cold water immersion were all recommended - in addition to simply being chained to a wall for weeks on end.

Picture Nottingham

Picture NottinghamVictoria Sweetmore, head of mental health and learning disability nursing at the University of Derby, is also studying for a PhD on the history of nursing at the University of Nottingham.

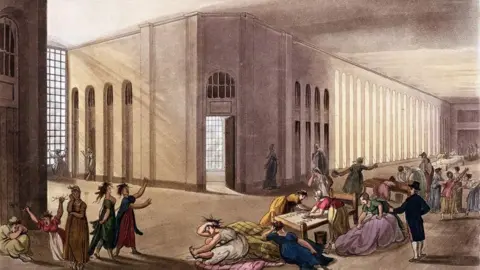

"What you had is people living in private mad houses, private institutions," she said. "There was absolutely no kind of oversight of these places, they were just run by anybody who fancied running one.

"There were no standards. There was just nothing. So people were kept in appalling conditions, you know, kind of chained up left with rags, fed scraps.

"On top of that they were treated like zoos, with people paying to come and see the inmates."

For a time in the 18th Century, Bedlam was the second most popular attraction in London and measures had to be taken to deal with visitor overcrowding during the Christmas and Easter holidays.

This in turn attracted thieves, pedlars and prostitutes, but also a level of critical scrutiny.

Nottingham Local Studies Library

Nottingham Local Studies LibraryMs Sweetmore said: "It was increasingly felt that this wasn't acceptable.

"So there was this real push towards making sure that as a society we were looking after people, particularly what they term the pauper lunatics who were either being held in workhouses, in prisons, at home or often just forced to wander the streets."

The issue was also twice highlighted by King George III who in 1788 suffered a mental breakdown, and then in 1800 survived an assassination attempt by a man who was saved from the noose by a new and much wider application of the insanity plea.

This led to the County Asylums Act 1808, which allowed local authorities to raise public funds for the care of mentally ill people in regulated institutions.

After years of fitful private fundraising, this spurred community leaders in Nottingham to open the Nottingham General Lunatic Asylum.

Sited in extensive gardens in the fields of Sneinton, shielded from public gaze and away from the noise of the city, it was the first of its kind in the country.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr Whitfield said a new ethos of "moral treatment" did not mean a move to modern standards.

He said: "Looking back, it seems very dark to us because of the kind of treatments that were used back then.

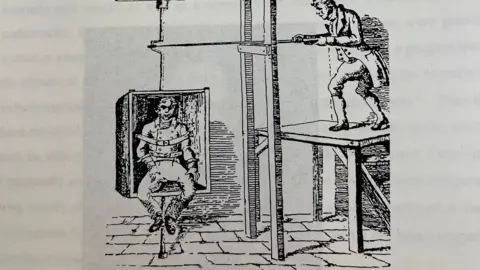

"There was the chair, the purges, the emetics, all these things that were designed to try and essentially drag bad things out of people, which is how it was seen.

"Having said that, at the time, it was set up to be quite humane.

"The rooms were clean, the patients had privacy, restraints were kept to a minimum and staff were instructed to display "tenderness and gentleness"."

Possible insights into the limits of the therapies available at Nottingham comes from the 1814 accounts which show that of the £1427 annual spend, £137 went on beer and ale, £9 9s on wine and just £7 6s on medicines.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr Whitfield turned some of findings into his novel, focusing on a real life patient, Mary Reddish.

When admitted in 1827 her first medical record stated "her moral conduct has not been correct".

"That's the only clue as to what she really had," he said.

"Her notes go on to say "violent, incoherent, impetuous" and she is described as a "violent lunatic" – but in terms of diagnosis in terms of what we would know it, that is completely absent.

"But when you look at it in a broader sense, in particular why women were in there, they seem to be things we think of as common today.

"Things that sound like post natal depression, menopause - or a "change in constitution" as it was described - and "disappointed affection" which could simply be a bad break up."

Dakeyne Farm

Dakeyne Farm

Mary was subjected to the chair, which spun the patient around until they passed out.

Remarkably, it was reported that "good effects are ascribed to the chair and she continues to improve in mind and body".

Mr Whitfield said: "Who knows what this really means? I've had to take a view of this in the book but you can only go on what the doctor has chosen to write down at the time."

While 'treatments' like spinning and blistering were phased out, Nottingham's asylum soon came to face a challenge common with modern healthcare - overcrowding.

Originally built to house 80 people, by the end of 1857 it held 247 - 130 men and 117 women.

Of these 31 were deemed potentially curable.

Dakeyne Farm

Dakeyne Farm

The fate of the incurable can also be glimpsed the same year, when the last remaining private patient, a woman, died after almost 39 years in the asylum.

The decades took their toll on the institution, and with patient numbers still climbing, new asylums had to be built further out.

By 1891, with buildings aging and the expanding city crowding around, commissioners described the original asylum as "inconvenient, ill constructed [and] ill adapted".

It closed in 1902, with most of the buildings knocked down soon after - though the site, now a public park, was not fully cleared until the 1960s.

The only reminder is a plaque on the final surviving fragment, a red brick pillar which formed part of an entrance gate.

Ms Sweetmore added: "Asylums were largely closed down in the late 20th Century but places like Nottingham, for all their failings, were a big step away from what went before."

Follow BBC Nottingham on Facebook, on X, or on Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected] or via WhatsApp on 0808 100 2210.