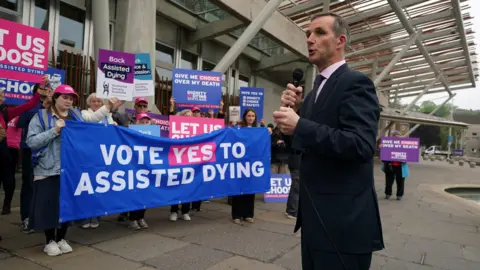

Liam McArthur: Who is the MSP behind the assisted dying bill?

PA Media

PA MediaFor almost two decades, Orkney MSP Liam McArthur has been quietly focussed on addressing local concerns on the islands he represents rather than seeking a national profile.

But now he has been placed firmly in the spotlight by his stewardship of the assisted dying bill, which this week passed its first hurdle in the Scottish Parliament.

MSPs had voted against two previous attempts to change the law in 2010 and 2015.

McArthur had voted in favour of both those bills before deciding to have a go himself at making it legal for terminally ill adults to seek medical help to end their lives.

He is probably one of the best placed politicians to champion such an emotive cause.

Not because he has family experience of a particularly traumatic end of life situation - he has said he does not.

Instead, it is because of his personality and approach to politics.

McArthur family

McArthur familyMcArthur is a very understated MSP.

He doesn't tend to flap or get furious and he has worked hard to build friendly working relationships with politicians in all parties.

He has won praise from the first minister down for the way he has conducted himself in discussions over assisted dying - respecting all opinions and listening to suggestions for how his proposals could be improved.

That has helped him build support beyond his own expectations.

He repeatedly said the vote on his bill was likely to be tight. When it came, he won by 70 votes to 56 with one abstention - a larger margin of victory than his team had anticipated.

Not that his response was in any way triumphalist.

Instead, he was tearful - and relieved to know that his years of meticulous work resulted in a vote in principle for assisted dying.

PA Media

PA MediaMcArthur has succeeded where previous sponsors of assisted dying proposals in ther Scottish Parliament - Jeremy Purvis and then Patrick Harvie, on behalf of the late Margo MacDonald - failed to win sufficient support.

He decided to build on their legacy after being re-elected in 2021, making the judgement that the mood of parliament had changed with its new membership.

He was right.

That shift in opinion may reflect the normalisation of so-called "right to die" provisions by their introduction in other countries, and possibly the wider discussions about death prompted by the pandemic.

A separate proposal on assisted dying for England and Wales is working its way through the UK parliament.

Liam McArthur was born in Edinburgh and grew up there until his family moved to Orkney when he was 10 years old.

He returned to Edinburgh to study politics and got his first job after university as a researcher at Westminster to the then Lib Dem MP for Orkney and Shetland, Jim Wallace.

He has had various roles in public affairs and political consultancy, including a spell in Brussels where he met his wife Tamsin. They have two children and Gerry the dog.

Despite one colleague describing him as "bomb-proof" for his cool-headed approach at work, he also earned a reputation as a highly competitive footballer in his student life and at Holyrood.

McArthur family

McArthur familyHe was elected as an MSP in 2007. Before then he worked behind the scenes in the Scottish government as a special advisor to the deputy first minister Jim Wallace when the Liberal Democrats shared power with Labour.

He is now a deputy presiding officer in the Scottish Parliament, which means he helps to run the place and chairs some of its debates.

Many MSPs come and go at Holyrood without achieving much of public note.

Depending on what happens next, the approval in principle of his assisted dying bill could come to be seen as one of the most significant moments in the Scottish Parliament's short history.

PA Media

PA MediaMcArthur is well aware that some of his MSP colleagues still have deep reservations and only voted "yes" to see if their concerns could be addressed in the next phase of debate.

He knows there are worries about how the law would operate in practice, about how it could alter the relationship between doctors and their patients, and about how it could make some vulnerable people who want to live feel a sense of obligation to seek a premature death.

McArthur has said he is particularly sympathetic to points raised by disabled rights campaigners because his own brother Dugald is quadriplegic following a rugby accident.

He has made clear a willingness to listen to these arguments and stresses he is open to changing his bill to tighten safeguards and to try to allay concerns.

For example, he has already agreed to raise the proposed age at which someone could seek to end their life from 16 to 18.

The details of this bill will be debated and potentially changed significantly in the coming months before it goes to a final vote of the whole Scottish Parliament.

Between now and then, McArthur will need to deploy all his skills of quiet persuasion if assisted dying is to become a legally available option in Scotland.