Sneaky Britain? How our moral compasses are changing

BBC

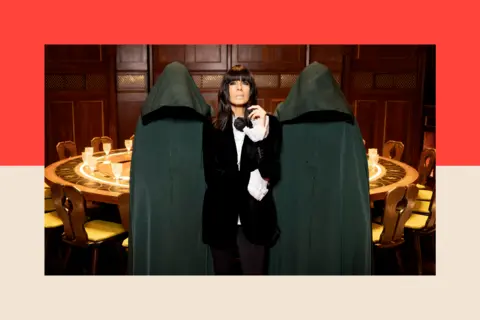

BBC"We're killing a priest!" says Minah, dressed head to toe in a dark green cloak. "I know. Oh my God! Lord have mercy," giggles Charlotte in a soft Welsh accent. Only Charlotte, a contestant in gameshow The Traitors, isn't really Welsh and their "victim" was pretending not to be a priest until episode five.

There's another twist, too - because although Minah thinks she and Charlotte are a rock-solid team, Charlotte seems to be preparing to throw Minah under a bus.

The UK, it appears, can't get enough of betrayal, backstabbing and all-out duplicity. The first episode of the latest series of The Traitors - the finale of which airs on Friday - has been watched by over 10m viewers to date.

In the latest series a group of 25 strangers set out to unmask so-called traitors in their midst to win a prize fund of up to £120,000; the traitors, in turn, "murder" the others (known as faithfuls) each episode, in their attempt to keep the winnings for themselves.

It's an engaging concept. But could the popularity of this show, based on deception and double-dealing, tell us something fundamental about the contemporary British psyche?

BBC/PA

BBC/PALast year Dr David Shepherd, a criminologist at the University of Portsmouth, led a study on the UK public's tendency towards dishonesty - it suggested that the nation was becoming a more dishonest place where disapproval of various underhand activities had fallen noticeably.

He argues that this showed that "overall, there has been a decline in honesty" across the UK.

Is the UK becoming more dishonest?

This isn't the first time that it has been suggested that the UK is becoming more dishonest. The British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey, an annual statistical study that has been running since 1983, also offered some insight.

Given a scenario in which an unemployed person on benefits took a casual job that he did not declare, leaving him £500 in pocket, some 53% of respondents in 2022 believed that this was wrong - down from 68% in 2016.

Asked about a scenario where the sum was £3,000, the percentage who said it was wrong fell from 80% to 66% in the same period.

Wilf Webster, 32, a former charity worker who was a contestant on the first UK series of the show - and won popularity among fellow contestants despite being cast in the role of a traitor - says that he has observed an increased prevalence of lying in day-to-day life.

"We all have this little bit of deceitfulness inside us," he argues. "It's become a lot more acceptable. If you tell your friends, 'oh I've just pulled a sickie', people laugh about it."

The average Briton lies 2.08 times a day, according to a study from 2014. However, there is no recent equivalent study to which to compare this. And dishonesty can be very difficult to measure. After all, people might not want to admit too readily to lying.

"Where you're dealing with deceitfulness or lying, or things that are potentially morally wrong, it's a little bit more difficult than subjects that are less contentious to get people's unequivocal view," says Alex Scholes, research director at the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen).

Measuring serious dishonesty

Nonetheless, in 2023 Dr Shepherd and his team attempted to quantify the extent to which the UK's tendency towards dishonesty had changed over time.

They revisited a study published in 2011 about the UK public's attitudes towards various acts that could be considered errant or dishonest. These included keeping excess change that was given mistakenly in a shop; lying in one's own interests; and committing benefit fraud.

The original respondents had been asked to what extent these behaviours could be justified on a scale of one to four and given an "integrity score". Twelve years on, Dr Shepherd's researchers repeated the exercise with 1,000 British adults.

They found that when it came to relatively minor dishonest acts or those which were not illegal - such as lying in one's own interests, dodging a fare, falsifying a CV, or having an affair while married - the proportion who said they were never acceptable was much the same in 2023 as in 2011.

However, when it came to more serious dishonesty of a criminal nature, the 2023 survey observed there had been a noticeable fall in the number of people who said particular acts were never acceptable. These included buying stolen goods, accepting a bribe and falsifying a benefits claim. The latter saw the biggest decline, dropping 18 percentage points from 85% to 67%.

And this large drop in the British public's disapproval of these more serious acts was steep enough for Dr Shepherd to conclude that honesty across the UK had declined overall.

"We can see a change in dishonest disposition over that decade or so," he says.

Old vs young, men vs women

Dr Shepherd believes it may be relevant that the shift in attitudes towards more serious acts of dishonesty was driven principally by "young people, especially younger men".

"Younger people are more dishonest, and males are more dishonest than females", he adds, based on the findings of his study.

As for older age groups, the scores of those aged 55 and above had not noticeably shifted. "The dishonesty of younger men has shifted more than any other age category," he argues.

In all, 28% of males aged between 18 and 25 were found to have "high-honesty dispositions", compared with 98% of females aged 66 and above.

"In other words, dishonesty is prevalent amongst 72% of young men compared to 2% of older women," concludes Dr Shepherd.

From politicians to social media

Given this sharp age divide, Dr Shepherd speculates that social media may have had a role in encouraging toxic behaviour, offline. But in his view that is not the only factor.

"Look at the bad behaviour of some corporations. Look at the bad behaviour of our politicians, even sports people - and how those behaviours are lauded in certain circles."

Wilf Webster agrees. "Years ago, we'd look up to politicians," he says. But high-profile scandals have, in his view, led more people to conclude "if they're doing it, I'm doing it too".

"I remember looking at politicians very differently [after leaving The Traitors]," he continues. "I remember thinking, when they go into Parliament it's as though they put on these green cloaks. It's like being in the castle, you don't know who to trust and whether people are telling the truth."

BBC/PA

BBC/PABut whatever the underlying causes, any rise in deceitfulness would be a troubling one. A modern market economy like the UK depends on a basic assumption of truthfulness, points out Dr David Hugh-Jones, a social scientist formerly based at the University of East Anglia.

"If you have an advanced capitalist society, it kind of runs on trust to a certain degree. You can't have a stock market without a basic level of trust in the accounts of the companies you're investing in," he says.

"If I take my car into the mechanics, I've got to trust that he's not just going to bash it with his spanner and charge me a grand."

A troubling trend for society

There are certain reasons to be cautious about the extent to which we can say with confidence that the UK has become more dishonest.

Take the BSA figures showing a decline in the proportion of people who think £500 worth of benefit fraud is wrong. This is a "notable trend", says Alex Scholes of NatCen, which carries out the survey, but he argues that there are certain caveats.

Firstly, defrauding £500 from the system in 2016 was a different matter to doing the same in 2022, simply because of the rate of inflation.

There are also indications that attitudes have become "a bit more sympathetic" towards benefit claimants in general, Mr Scholes says - and in turn, this, rather than a rise in dishonesty, could be driving the change in responses to the £500 question.

Paul Whiteley, emeritus professor of government at the University of Essex, who authored the 2011 study that Dr Shepherd and his team later revisited, points to a separate research project about values and beliefs, conducted by social scientists, which found much less of a change over the years in answers to certain questions about honesty. This included some scenarios also involving government benefits.

That separate study also indicates that "cheating on taxes and accepting bribes has become more unacceptable", argues Prof Whiteley. "So there isn't really a uniform trend."

How Japan, China and Turkey fared

There is at least some evidence, too, to suggest that the UK is fairly honest compared with other countries.

In 2016, a study compared the honesty of people in 15 different countries by asking more than 1,500 participants to take part in two tests - a coin flip and an online quiz - after which it was possible to determine if they had cheated.

With the coin flip, the estimated rate of dishonesty ranged from 3.4% in the UK to 70% in China. In the quiz, Japanese respondents were the most honest, with the UK in second place and those from Turkey coming last.

The person behind the study - Dr David Hugh-Jones, a social scientist then based at the University of East Anglia - determined that Britons, like most other nationalities, typically think their fellow countryfolk are more dishonest than they actually are. "People tend to be very pessimistic about the honesty of their own country," he says.

"If you ask them 'will people in your country be honest?' they are usually rather pessimistic but they naively believe that people in other countries are much better."

So even if the British are becoming more dishonest, they might not necessarily be any worse than their neighbours.

A more dishonest future?

As for the future, Prof Whiteley speculates the UK may be about to become somewhat less honest. He puts this down to crime incidents rising 10% in the year to June 2024, according to figures from the Office for National Statistics.

This, he says, is "going to make people less trusting and possibly more dishonest".

If he's correct, there will be plenty of worthy candidates for future series of The Traitors.

The show has some echoes of a party game called Mafia - also known as Werewolf - which is generally acknowledged to have been invented in the 1980s by Dmitry Davidoff at Moscow State University's psychology department. Invented amid the paranoia and mistrust of the crumbling Soviet system, the game quickly became a huge hit.

So while it's tempting to look at what The Traitors phenomenon tells us about the state of contemporary society, there's another possible explanation - that it speaks to an eternal truth about humans' disposition to dishonesty down the ages.

As Wilf Webster puts it: "We all have an instinct to be deceitful.

"Probably not one person I've spoken to in my life has never told a lie for their own benefit."