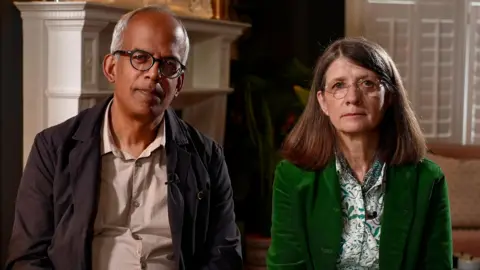

We quit our jobs, sold our home twice and spent 10 years fighting for the truth

Family handout

Family handoutWARNING: This article contains upsetting details and reference to suicide

There didn't seem to be anything out of the ordinary when Jane Figueiredo spoke to her daughter that night on the phone.

"Alice asked me to bring her some snacks for the next time we visited," Jane says. But that call, at 22:15 on 6 July 2015, was the last conversation they ever had.

Around three hours later, Jane and her husband, Max, were being driven to hospital in a police car at speed. They had been told their daughter was gravely ill.

Alice had got into a communal toilet at Goodmayes Hospital, in Ilford, east London, where she was a mental health patient, and took her own life using a bin liner. She was just months away from her 23rd birthday.

On Monday, almost 10 years later, the North East London NHS Foundation Trust (NELFT), which runs the hospital, and Benjamin Aninakwa, the manager of the ward Alice was on, have been found guilty of health and safety failings over her death.

The jury decided not enough was done by NELFT, or Aninakwa, to prevent Alice from killing herself.

'You are not above the law'

It's taken a decade of battling by Alice's parents to uncover the truth about how the 22-year-old was able to take her own life in a unit where she was meant to be safe.

They twice had to sell their home, quit their jobs and have worked full-time on the case.

The jury deliberated for 24 days to reach all the verdicts, after which time the Trust was cleared of the more serious charge of corporate manslaughter, while Aninakwa, 53, of Grays, Essex, was cleared of gross negligence manslaughter.

During the seven-month trial, we sat a few seats away from the family. They've sometimes been overwhelmed, leaving the court angry or in tears, as they felt their voices - and that of Alice - were not being heard.

Now, Jane hopes the verdicts will bring major change to psychiatric care providers around the country. "You need to do far, far better to stop failing those people who you have a duty of care to," she said after the verdict.

Weeks earlier, in mid-March this year, the Figueiredos were living in a hotel room in central London.

While folding their clothes, they spoke to the BBC during a break in the trial, which was already running months longer than expected.

They had been living out of suitcases since the end of October, when court hearings began.

Even before the pain of hearing evidence about their daughter's death, they said simply existing like this had been a huge challenge.

For the couple, it was important to be at the Old Bailey every day in person - no matter the cost - because they felt this was their only chance to see the Trust held to account for their daughter's death.

Sensitive and caring

Alice was born in 1992, the second of three daughters. She was a bright and energetic child, and often the centre of attention. She loved music, poetry, reading and, in particular, art. Family and friends say she had a big personality.

"She had a really deeply thoughtful, sensitive, caring nature. She was really kind. She was really generous," remembers Jane.

As a child, Alice started to develop what became an eating disorder, and by 15 she was showing symptoms of severe depression and was admitted to a mental health unit.

In the following years she would be hospitalised on many more occasions.

In 2012, then 19, she was admitted to the Hepworth Ward, at Goodmayes Hospital, for the first time. It is an inpatient mental health unit for women, run by NELFT. She was admitted there a total of seven times over the following three years.

"She needed safety. She was a risk to herself," says Jane.

"It was a question of, somehow managing the crisis and trusting the medical profession to make the right decisions," adds Max, Alice's stepfather.

Between admissions, Alice had long periods when hospital treatment wasn't needed. She had been applying to go to university and was planning a brighter future.

But on 13 February 2015, as her mental health took a serious turn for the worse, Alice was admitted to the Hepworth Ward for what would prove to be the final time.

Three days later, Alice was detained on the unit under section three of the Mental Health Act to undergo treatment for her own safety and could not leave without her consultant's permission.

Alice was put on one of the highest observation levels, reserved for patients at most risk of harming themselves. It meant a member of staff had to stay within arm's length of her 24-hours-a-day.

In a letter to staff just over a month into her admission, Max and Jane wrote: "She cannot contain the sense of sheer torment, intense depression and overwhelming despair she is experiencing."

Family handout

Family handoutThe manager for Hepworth Ward at the time was Benjamin Aninakwa. The now 53-year-old had been working on the unit since it opened, in 2011. He was in charge of the unit during each of Alice's previous admissions, so knew her well.

But other things on the ward had changed. The nurse and the consultant, who had previously cared for Alice, had both moved on and there was a high level of temporary agency staff filling long-standing gaps in the rota. Her parents say Alice felt unsettled.

"I think it became clear that there was an element of chaos in the ward," says Max.

Jane, who was a chaplain to the mental health trust, would visit Alice every day; Max, who worked for the NHS as an accountant, would stop by a few times a week, often with food.

Alice told her parents that staff weren't carrying out observations properly. On one occasion, within the first fortnight of her admission, she said an agency health care assistant who was supposed to be staying close to her, was instead making a phone call.

The family later saw an internal email saying Alice had been left alone while the care worker continued this conversation. In that time, Alice attempted to harm herself using her bedding.

The same email said that once the care assistant returned and found Alice she slapped her. "Nothing was done about that. There was no safeguarding," says Jane.

During the trial, the court heard that Alice had attempted to harm herself on at least 39 occasions during her admission - many of these involved plastic bags or bin liners.

Even though they were in the dark about many of these incidents, her parents became so concerned they started raising it with staff at the hospital, in person and in several emails.

On 16 May, three months into Alice's stay, Jane emailed the consultant for Hepworth Ward, Dr Anju Soni, about an incident of self-harm with a plastic bag in which Alice lost consciousness.

"If it had been a few minutes longer before she was found, the outcome could have been very different - she could have died," she wrote.

The court heard that many of these incidents were not recorded properly by staff, nor communicated to the family.

After several months, Alice's depression began to ease. In June, her observation levels were lowered to reflect her progress, and they were eventually reduced to hourly checks.

She was able to leave the unit for short periods, even going to a Fleetwood Mac concert with her boyfriend Andrew.

But her eating disorder remained a serious challenge, and she was still under section. She asked to be moved to a specialist unit to help her recovery.

On 30 June, Alice complained of chest pain and was transferred to nearby King George Hospital. When she came back to Hepworth Ward a couple of days later, the court heard she was told she was too frail to go on planned leave.

Her family remember intense fluctuations in her mood around this time. They say she was frustrated that her eating disorder wasn't improving, little progress was being made on her moving to another unit and she was getting bullied by other patients on the ward.

On 4 July, three days before Alice died, Jane and Max went to visit her. The eating disorder was taking its toll. They could see their daughter was struggling.

"She sat there almost in silence, tears were rolling down her face," remembers Jane.

Late on the night of 6 July, Alice and her boyfriend exchanged messages with each other, talking about their love of Bob Dylan's music. At 23:30 he wrote: "I can't stop thinking about you, x."

The court heard that around that time Alice had asked to speak to a care assistant she got on with.

The care assistant was called away to an emergency elsewhere in the hospital. When she returned to Hepworth Ward she looked for Alice. She eventually found her slumped in the communal toilet.

Errors by two nurses on duty on Hepworth Ward slowed the arrival of an on-call doctor and paramedics. Alice was eventually taken to another hospital where she died.

"It's a moment where your entire life has changed and will never be the same. That's what we have had to learn to live with," says Jane.

Still dealing with the devastating shock of losing their daughter, the Figueiredos set about piecing together what had happened to her.

The Trust produced a Serious Incident (SI) report. These investigations are meant to help prevent similar incidents happening.

But the Figueiredos felt it was incomplete and the Trust was avoiding accepting responsibility for Alice's death.

Whatever their concerns, the report contained information that was new and troubling. It mentioned 13 incidents in which Alice had used a plastic bag or bin bag to self-harm.

"I was shocked and horrified when I saw that," says Jane. "I thought, [the Trust] knew this had happened, and [they] still let her carry on doing this, and she died," she says.

The family felt the risk of plastic bags for patients on an acute mental health ward, particularly Alice, should have been obvious.

During a previous admission to Hepworth Ward the year before, Alice tried to harm herself using plastic bags on at least three occasions.

In November 2015, sensing there was more to uncover, the couple holed themselves up in a hotel in Lindisfarne, off the Northumbria coast, and started piecing together their suspicions.

"We went very quickly into actually writing our own report and sending it to all the authorities that we knew of," says Max.

They used their insiders' knowledge from working in the health service, to get their report in front of senior NHS people and regulators. They wrote to Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, then head of London's Metropolitan Police.

He wrote back and a police investigation into what happened to Alice was launched. The Nursing and Midwifery Council launched inquiries into several of the nurses involved in Alice's care.

Even with the police involved, the Figueiredos kept digging, getting hold of as much documentation as they possibly could. When they weren't able to get documents through official routes, they'd find other ways to get them, working like seasoned investigators.

Once they had them, they'd analyse them and produce detailed reports that they sent to the police and regulators.

"If I could discover something that would be helpful to their investigation. I would try to do that. We were a parallel investigation," says Jane.

Family handout

Family handoutAll this digging came at a financial cost.

"We were in our 50s, we both stopped working and actually sold our house and lived off that to be able to do this," says Jane.

The emotional price was even higher. "You can't underestimate or even find the words to say, the toll that that takes on you. It's profoundly re-traumatising," she says.

There were further shocks to come in Alice's medical notes, which showed gaps in the hospital's official SI report. They had been told Alice had attempted to self-harm with plastic bags on 13 occasions, in fact it happened at least 18 times.

Most of these incidents weren't recorded in logs as they should have been.

"It still shocks us to the core today," says Max.

On the unit, plastic bags were not used in the bins in patient bedrooms for safety reasons, but they were in a few communal locations, including a toilet that was often left unlocked. Alice used these bags to self-harm on multiple occasions, including the incident that led to her death.

The trial heard there was little evidence that ward manager Benjamin Aninakwa made any attempt to restrict access to those bin bags, despite the issue being raised with him, and it appearing in Alice's care plan.

He did not appear as a witness in court but told police the toilet door was locked and he had been overruled when he tried to remove the bin bags. The court heard there were no emails or evidence in Alice's clinical notes and records to corroborate this.

A Care Quality Commission inspection in April 2016, the year after Alice's death, found bin bags still being used on the unit. The bags were eventually removed.

The court heard that around the time Alice was admitted to the hospital for the final time, the Trust was carrying out a "scoping exercise", which looked at removing all plastic bin bags from the hospital's wards. It was revealed a bin which didn't need a plastic liner had been considered – it would have cost just £1.26.

"NELFT placed more value on their rubbish bins than they did on my daughter's life," says Jane.

In a statement, the Trust said: "Our thoughts are with Alice's family and loved ones, who lost her at such a young age. We extend our deepest sympathy for the pain and heartbreak they have suffered this past 10 years.

"We will reflect on the verdict and its implications, both for the trust and mental health provision more broadly as we continue to work to develop services for the communities we serve."

Jane and Max Figueiredo say they wanted to hold those at the Trust to account, but that they also wanted change for the future. But there will be no celebration at Monday's verdicts.

"Nothing will ever bring Alice back to us and we will never stop thinking of her and missing her," says Jane. "There's always one place empty at our table, one very special voice silent that we long to hear in our conversations."

If you are suffering distress or despair, details of help and support in the UK are available at BBC Action Line.