Five key impacts of Brexit five years on

EPA-efe/rex/shutterstock

EPA-efe/rex/shutterstockFive years ago, on 31 January 2020, the UK left the European Union.

On that day, Great Britain severed the political ties it had held for 47 years, but stayed inside the EU single market and customs union for a further 11 months to keep trade flowing.

Northern Ireland had a separate arrangement.

Brexit was hugely divisive, both politically and socially, dominating political debate and with arguments about its impacts raging for years.

Five years on from the day Britain formally left the EU, BBC Verify has examined five important ways Brexit has affected Britain.

1) Trade

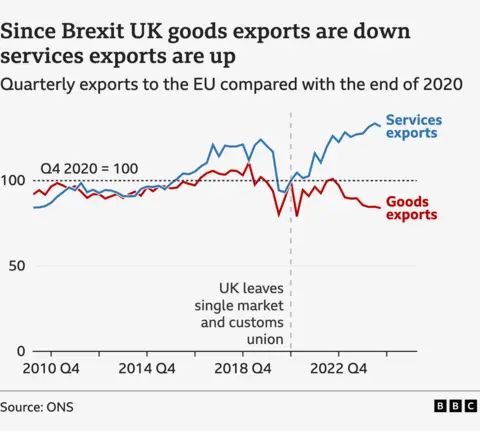

Economists and analysts generally assess the impact of leaving the EU single market and customs union on 1 Jan 2021 on the UK's goods trade as having been negative.

This is despite the fact that the UK negotiated a free trade deal with the EU and avoided tariffs - or taxes - being imposed on the import and export of goods.

The negative impact comes from so-called "non-tariff barriers" - time consuming and sometimes complicated new paperwork that businesses have to fill out when importing and exporting to the EU.

There is some disagreement about how negative the specific Brexit impact has been.

Some recent studies suggest that UK goods exports are 30% lower than they would have been if we had not left the single market and customs union.

Some suggest only a 6% reduction.

We can't be certain because the results depend heavily on the method chosen by researchers for measuring the "counterfactual", i.e what would have happened to UK exports had the country stayed in the EU.

One thing we can be reasonably confident of is that small UK firms appear to be more adversely affected than larger ones.

They have been less able to cope with the new post-Brexit cross-border bureaucracy. That's supported by surveys of small firms.

It's also clear UK services exports - such as advertising and management consulting - have done unexpectedly well since 2021.

But the working assumption of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the government's independent official forecaster, is still that Brexit in the long-term will reduce exports and imports of goods and services by 15% relative to otherwise. It has held this view since 2016, including under the previous Government.

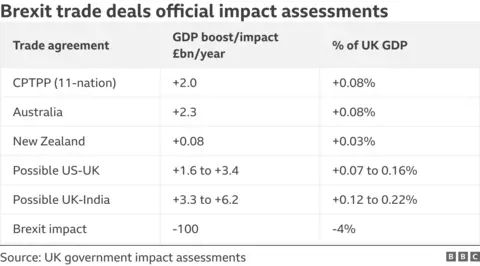

And the OBR's other working assumption is that the fall in trade relative to otherwise will reduce the long-term size of the UK economy by around 4% relative to otherwise, equivalent to roughly £100bn in today's money.

The OBR says it could revise both these assumptions based on new evidence and studies. The estimated negative economic impact could come down if the trade impact judged to be less severe. Yet there is no evidence, so far, to suggest that it will turn into a positive impact.

After Brexit, the UK has been able to strike its own trade deals with other countries.

There have been new trade deals with Australia and New Zealand and the government has been pursuing new agreements with the US and India.

But their impact on the economy is judged by the government's own official impact assessments to be small relative to the negative impact on UK- EU trade.

However, some economists argue there could still be potential longer term economic benefits for the UK from not having to follow EU laws and regulations affecting sectors such as Artificial Intelligence.

2) Immigration

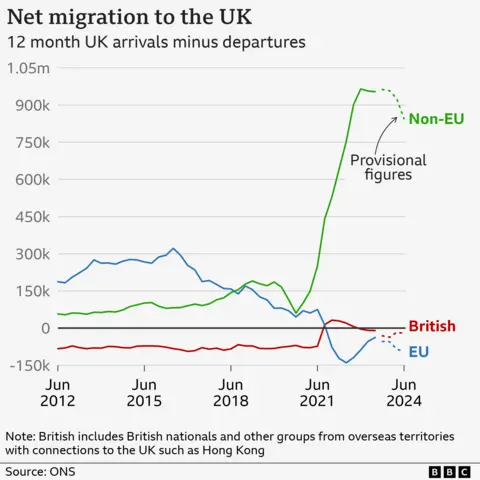

Immigration was a key theme in the 2016 referendum campaign, centred on freedom of movement within the EU, under which UK and EU citizens could freely move to visit, study, work and live.

There has been a big fall in EU immigration and EU net migration (immigration minus emigration) since the referendum and this accelerated after 2020 due to the end of freedom of movement.

But there have been large increases in net migration from the rest of the world since 2020.

A post-Brexit immigration system came into force in January 2021.

Under this system, EU and non-EU citizens both need to get work visas in order to work in the UK (except Irish citizens, who can still live and work in the UK without a visa).

The two main drivers of the increase in non-EU immigration since 2020 are work visas (especially in health and care) and international students and their dependents.

UK universities started to recruit more non-EU overseas students as their financial situation deteriorated.

The re-introduction of the right of overseas students to stay and work in Britain after graduation by Boris Johnson's government also made the UK more attractive to international students.

Subsequent Conservative governments reduced the rights of people on work and student visas to bring dependents and those restrictions have been retained by Labour.

3) Travel

Freedom of movement ended with Brexit, also affecting tourists and business travellers.

British passport holders can no longer use "EU/EEA/CH" lanes at EU border crossing points.

People can still visit the EU as a tourist for 90 days in any 180 day period without requiring a visa, provided they have at least three months remaining on their passports at the time of their return.

EU citizens can stay in the UK for up to six months without needing a visa.

However, a bigger change in terms of travel is on the horizon.

In 2025, the EU is planning to introduce a new electronic Entry Exit System (EES) - an automated IT system for registering travellers from non-EU countries.

This will register the person's name, type of the travel document, biometric data (fingerprints and captured facial images) and the date and place of entry and exit.

It will replace the manual stamping of passports. The impact of this is unclear, but some in the travel sector have expressed fears it could potentially add to border queues as people leave the UK.

The EES was due to be introduced in November 2024 but was postponed until 2025, with no new date for implementation yet set.

And six months after the introduction of EES, the EU says it will introduce a new European Travel Information and Authorization System (ETIAS). UK citizens will have to obtain ETIAS clearance for travel to 30 European countries.

ETIAS clearance will cost €7 (£5.90) and be valid for up to three years or until someone's passport expires, whichever comes first. If people get a new passport, they need to get a new ETIAS travel authorisation.

Meanwhile, the UK is introducing its equivalent to ETIAS for EU citizens from 2 April 2025 (though Irish citizens will be exempt). The UK permit - to be called an Electronic Travel Authorisation (ETA) - will cost £16.

Reuters

Reuters4) Laws

Legal sovereignty - the ability of the UK to make its own laws and not have to follow EU ones - was another prominent Brexit referendum campaign promise.

To minimise disruption immediately following Brexit in 2020, the UK incorporated thousands of EU laws into UK law, becoming known as "retained EU law".

According to the latest government count there were 6,901 individual pieces of retained EU law covering things like working time, equal pay, food labelling and environmental standards.

The previous Conservative government initially set a deadline of the end of 2023 to axe these EU laws.

But with so much legislation to consider there was concern there was not enough time to review all the laws properly.

In May 2023 Kemi Badenoch - the Trade Secretary at the time - announced only 600 EU laws would be axed by the end of 2023, with another 500 financial services laws set to disappear later.

Most were relatively obscure regulations and many of them had been superseded or become irrelevant.

All other EU legislation was kept, though ministers reserved powers to change them in future.

And the UK has changed some EU laws. For example, it banned the export of live animals from Great Britain for slaughter and fattening and changed EU laws on gene editing crops.

Brexit has also given the UK more freedom in certain areas of tax law.

EU member states are prohibited from charging VAT on education under an EU directive. Leaving the EU enabled Labour to impose VAT on private school fees.

A zero rate of VAT on tampons and other sanitary products was introduced by the UK government in 2021. This would not have been possible in the EU as the EU VAT Directive at the time mandated a minimum 5% tax on all sanitary products. However, in April 2022 the EU's rules changed so the bloc also now allows a zero rate on sanitary products.

5) Money

The money the UK sent to the EU was a controversial theme in the 2016 referendum, particularly the Leave campaign's claim the UK sent £350m every week to Brussels.

The UK's gross public sector contribution to the EU Budget in 2019-20, the final financial year before Brexit, was £18.3bn, equivalent to around £352m per week, according to the Treasury.

The UK continued paying into the EU Budget during the transition period but since 31 December 2020 it has not made these contributions.

However, those EU Budgets contributions were always partially recycled to the UK via payments to British farmers under the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and "structural funding" - development grants to support skills, employment and training in certain economically disadvantaged regions of the nation. These added up to £5bn in 2019-20.

Since the end of the transition period UK governments have replaced the CAP payments directly with taxpayer funds.

Ministers have also replaced the EU structural funding grants, with the previous government rebranding them as "a UK Shared Prosperity" fund.

The UK was also receiving a negotiated "rebate" on its EU Budget contributions of around £4bn a year - money which never actually left the country,

So the net fiscal benefit to the UK from not paying into the EU Budget is closer to to £9bn per year, although this figure is inherently uncertain because we don't know what the UK's contribution to the EU Budget would otherwise have been.

The UK has also still been paying the EU as part of the official Brexit Withdrawal Agreement and its financial settlement. The Treasury says the UK paid a net amount of £14.9bn between 2021 and 2023, and estimated that from 2024 onwards it will have to pay another £6.4bn, although spread over many years.

Future payments under the withdrawal settlement are also uncertain in part because of fluctuating exchange rates.

However, there are other ways the UK's finances remained connected with the EU, separate from the EU Budget and the Withdrawal Agreement.

After Brexit took effect, the UK also initially stopped paying into the Horizon scheme, which funds pan-European scientific research.

However, Britain rejoined Horizon in 2023 and is projected by the EU to pay in around €2.4bn (£2bn) per year on average to the EU budget for its participation, although historically the UK has been a net financial beneficiary from the scheme because of the large share of grants won by UK-based scientists.

The future

There are, of course, a large number of other Brexit impacts which we have not covered here, ranging from territorial fishing rights, to farming, to defence. And with Labour looking for a re-set in EU relations, it's a subject that promises to be a continuing source of debate and analysis for many years to come.

Clarification: This article has been updated to clarify the amount of time EU citizens can spend in the UK, visa free.

Sign up for our Politics Essential newsletter to read top political analysis, gain insight from across the UK and stay up to speed with the big moments. It'll be delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.