'Future generations need cure' for brain disorder

BBC

BBCA woman who is at least the fourth generation of her family to suffer a "cruel" brain disorder, which leaves people trapped in their own bodies, is hoping a drug trial can give hope to future patients.

Samantha Dennison, 58, has neuroferritinopathy, a rare disease that mainly affects a small number of families with roots in Cumbria.

She is taking part in a trial to see if an existing drug, deferiprone, can remove the build-up of iron in the brain which causes the disease.

The condition, discovered by medics in Newcastle in 2001, usually results in patients losing the ability to talk or move while remaining fully aware of the world around them.

Scientists believe that worldwide there may only be about 100 people with neuroferritinopathy, but by the time they are diagnosed they may have children also carrying the gene.

Those who discovered and named the condition said it had often been misdiagnosed as Parkinson's or Huntington's disease prior to 2001.

One of the Newcastle scientists, Prof Patrick Chinnery, was so moved by the impact the condition had on patients and their families he became determined to find a treatment or, better still, a cure.

He is leading the DefINe trial at the University of Cambridge and described the condition as "cruel" because it left patients "trapped in", unable to communicate with those around them.

Whole families can be affected at once, including four sisters in Cumbria whose story the BBC featured last year, ahead of the Cambridge trial.

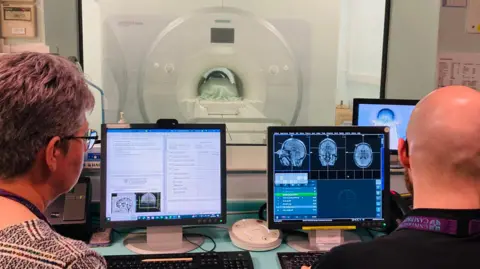

Mrs Dennison, from Bradford, was the first person to have her brain scanned for the study and recently returned to Cambridge for another MRI.

She now finds walking and talking difficult and said the condition had left a trail of destruction to her family.

"My brother has it, my father had it, his mother had it and so did her mother," she said.

Samantha's daughter, Steph, knew she was at risk of carrying the same gene and saw her grandfather deteriorate after he had been wrongly diagnosed with Parkinson's.

Witnessing her mother lose her ability to walk and talk, she said: "She used to love going out for long walks... she was bubbly and chatty."

Steph was terrified of finding out if the same thing was going to happen to her, to the extent that she feared having children of her own.

"I don't want them growing up and seeing me go through what my mum's gone through," she explained.

But she said not knowing was so stressful that she eventually agreed to be tested.

When the call came to say she did not have the gene, her and her partner burst into tears.

They are now expecting a baby.

'Potential cure'

The Cambridge trial, approved by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, is being supported by £750,000 from the LifeArc Rare Diseases Translational Challenge.

If successful, Prof Chinnery said doctors may be able to give deferiprone to people before they develop symptoms.

For patients, that means "a potential cure" and could pave the way for treating other conditions linked to the build-up of iron in the brain.

"If we can show in this condition that reducing iron stops the nerve cells being damaged, it is not a big jump to suggest a similar approach might be helpful in Parkinson's disease or Alzheimer's disease," Prof Chinnery added.

The trial is a double-blind study, so no one knows who is on the drug and who is taking the placebo, with researchers monitoring changes in iron levels in all participants.

Cambridge University is still recruiting trial subjects and if deferiprone - as an existing approved drug - works, it is hoped doctors will be able to prescribe it quickly.

With her own speech now slowing down, Samantha Dennison said her big wish was for future generations.

She said: "If they can have the disease stopped in its tracks, that would be absolutely amazing."

Follow BBC North East on X, Facebook, Nextdoor and Instagram and BBC Cumbria on X, Facebook, Nextdoor and Instagram. Send your story ideas here.