'You start to go crazy': The Australian who survived five years in a Chinese prison

EPA

EPASharing a dirty cell with a dozen others, constant sleep deprivation, cells with lights on 24-hours a day; poor hygiene and forced labour. These are some of what prisoners in Chinese jails are subjected to, according to Australian citizen Matthew Radalj, who spent five years at the Beijing No 2 prison – a facility used for international inmates.

Radalj, who is now living outside China, has decided to go public about his experience, and described undergoing and witnessing severe physical punishment, forced labour, food deprivation and psychological torture.

The BBC has been able to corroborate Radalj's testimony with several former prisoners who were behind bars at the same time he was.

Many requested anonymity, because they feared retribution on loved ones still living inside the country. Others said they just wanted to try to forget the experience and move on.

The Chinese government has not responded to the BBC's request for comment.

A harsh introduction

"I was in really bad shape when I arrived. They beat me for two days straight in the first police station that I was in. I hadn't slept or eaten or had water for 48 hours and then I was forced to sign a big stack of documents," said Radalj of his introduction to imprisonment in China, which began with his arrest on 2 January, 2020.

The former Beijing resident claims he was wrongfully convicted after a fight with shopkeepers at an electronics market, following a dispute over the agreed price to fix a mobile phone screen.

He claims he ended up signing a false confession to robbery, after being told it would be pointless to try to defend his innocence in a system with an almost 100% criminal conviction rate and in the hope that this would reduce the time of his incarceration.

Court documents indicate that this worked at least to some extent, earning him a four-year sentence.

Once in prison, he said he first had to spend many months in a separate detention centre where he was subjected to a more brutal "transition phase".

Matthew Radalj

Matthew RadaljDuring this time prisoners must follow extremely harsh rules in what he described as horrific conditions.

"We were banned from showering or cleaning ourselves, sometimes for months at a time. Even the toilet could be used only at specific allotted times, and they were filthy - waste from the toilets above would constantly drip down on to us."

Eventually he was admitted to the "normal" prison where inmates had to bunk together in crowded cells and where the lights were never turned off.

You also ate in the same room, he said.

According to Radalj, African and Pakistani prisoners made up the largest groups in the facility, but there were also men being held from Afghanistan, Britain, the US, Latin America, North Korea and Taiwan. Most of them had been convicted for acting as drug mules.

The 'good behaviour' points system

Radalj said that prisoners were regularly subjected to forms of what he described as psychological torture.

One of these was the "good behaviour points system" which was a way – at least in theory – to reduce your sentence.

Prisoners could obtain a maximum of 100 good behaviour points per month for doing things like studying Communist Party literature, working in the prison factory or snitching on other prisoners. Once 4,200 points were accumulated, they could in theory be used to reduce prison time.

If you do the maths, that would mean a prisoner would have to get maximum points every single month for three-and-half years before this could start to work.

Radalj said that in reality it was used as a means of psychological torture and manipulation.

He claims the guards would deliberately wait till an inmate had almost reached this goal and then penalise them on any one of a huge list of possible infractions which would cancel out points at the crucial time.

These infractions included - but were not limited to - hoarding or sharing food with other prisoners, walking "incorrectly" in the hallway by straying from a line painted on the ground, hanging socks on a bed incorrectly, or even standing too close to the window.

AFP/Getty

AFP/GettyOther prisoners who spoke about the points system to the BBC described it as a mind game designed to crush spirits.

Former British prisoner Peter Humphrey, who spent two years in detention in Shanghai, said his facility had a similar points calculation and reduction system which was manipulated to control prisoners and block sentence reductions.

"There were cameras everywhere, even three to a cell," he said. "If you crossed a line marked on the ground and were caught by a guard or on camera, you would be punished. The same if you didn't make your bed properly to military standard or didn't place your toothbrush in the right place in the cell.

"There was also group pressure on prisoners with entire cell groups punished if one prisoner did any of these things."

One ex-inmate told the BBC that in his five years in prison, he never once saw the points actually used to mitigate a sentence.

Radalj said that there were a number of prisoners - including himself - who didn't bother with the points system.

So authorities resorted to other means of applying psychological pressure.

These included cutting time off monthly family phone calls or the reduction of other perceived benefits.

Food As Control

But the most common daily punishment involved the reduction of food.

The BBC has been told by numerous former inmates that the meals at Beijing's No 2 prison were mostly made up of cabbage in dirty water which sometimes also had bits of carrot and, if they were lucky, small slivers of meat.

They were also given mantou - a plain northern Chinese bread. Most of the prisoners were malnourished, Radalj added.

Another prisoner described how inmates ate a lot of mantou, as they were always hungry. He said that their diets were so low in nutrition – and they could only exercise outside for half an hour each week – that they developed flimsy upper bodies but retained bloated looking stomachs from consuming so much of the mantou.

Prisoners were given the opportunity to supplement their diet by buying meagre extra rations, if money from relatives had been put into what were called their "accounts": essentially a prison record of funds delivered to purchase provisions like soap or toothpaste.

They could also use this to purchase items like instant noodles or soy milk powder. But even this "privilege" could be taken away.

Radalj said he was blocked from making any extra purchases for 14 months because he refused to work in the prison factory, where inmates were expected to assemble basic goods for companies or compile propaganda leaflets for the ruling Communist Party.

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesTo make things worse, they were made to work on a "farm", where they did manage to grow a lot of vegetables, but were never allowed to eat them.

Radalj said the farm was displayed to a visiting justice minister as an example of how impressive prison life was.

But, he said, it was all for show.

"We would be growing tomatoes, potatoes, cabbages and okra and then – at the end of the season – they would push it all into a big hole and bury it," he added.

"And if you were caught with a chilli or a cucumber in general population you would go straight to solitary confinement for eight months."

Another prisoner said they would occasionally suddenly receive protein, like a chicken leg, to make their diet look better when officials visited the prison.

Humphrey said there were similar food restrictions in his Shanghai prison, adding that this led to power struggles among the inmates: "The kitchen was run by prison labour. Those who worked there stole the best stuff and it could then be distributed."

Radalj described a battle between African and Taiwanese groups in Beijing's Prison No 2 over this issue.

The Nigerian inmates were working in the kitchen and "were getting small benefits, like a bag of apples once a month or some yogurt or a couple of bananas", he said.

Courtesy Matthew Radalj

Courtesy Matthew RadaljThen the Mandarin-speaking Taiwanese inmates were able to convince the guards to let them take over, giving them control of precious extra food items.

This led to a large brawl, and Radalj said he was caught in the middle of it. He was sent to solitary confinement for 194 days after hitting another prisoner.

Inside solitary, he finally had the lights turned off only to realise he'd be with very little light nearly all of the time, giving him the opposite sensory problem.

His small food ration was also cut in half. There were no reading materials and there was nobody to talk to while he was held in a bare room of 1.2 by 1.8 metres (4ft by 6ft) for half a year.

"You start to go crazy, whether you like it or not, and that's what solitary is designed to do… So you've got to decide very quickly whether your room is really, really small, or really, really big.

"After four months, you just start talking to yourself all the time. The guards would come by and ask 'Hey, are you okay?'. And you're like, 'why?'. They replied, 'because you're laughing'."

Then, Radalj said, he would respond, in his own mind: "It's none of your business."

Another feature of Chinese prison life, according to Radalji, was the fake "propaganda" moments officials would stage for Chinese media or visiting officials to paint a rosy picture of conditions there.

He said, at one point, a "computer suite" was set up. "They got everyone together and told us that we'd get our own email address and that we would be able to send emails. They then filmed three Nigerian guys using these computers."

The three prisoners apparently looked confused because the computers were not actually connected to the internet - but the guards had told them to just "pretend".

"Everything was filmed to present a fake image of prisoners with access to computers," Radalj said.

But, he claims, soon after the photo opportunity, the computers were wrapped up in plastic and never touched again.

The memoirs

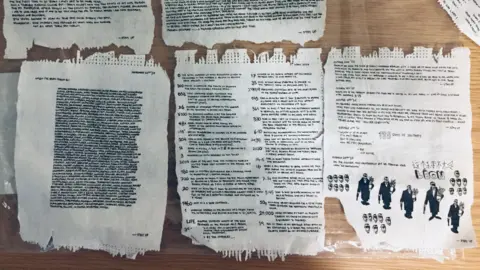

Courtesy Matthew Radalj

Courtesy Matthew RadaljThroughout much of the ordeal, Radalj had been secretly keeping a journal by peeling open Covid masks and writing tiny sentences inside, with the help of some North Korean prisoners, who have also since been released.

"I would be writing, and the Koreans would say: 'No smaller… smaller!'."

Radalj said many of the prisoners had no way of letting their families know they were in jail.

Some had not made phone calls to their relatives because no money had been placed in their accounts for phone calls. For others, their embassies had not registered family telephone numbers for the prison phone system. Only calls to officially approved numbers worked.

So, after word got round that the Australian was planning to try to smuggle his notes out, they passed on details to connect with their families.

"I had 60 or 70 people hoping I could contact their loved ones after I got out to tell them what was happening."

He wrapped the pieces of Covid mask as tight as he could with sticky tape hoarded from the factory and tried to swallow the egg-sized bundle without the guards seeing.

But he couldn't keep it down.

The guards saw what was happening on camera and started asking, "Why are you vomiting? Why do you keep gagging? What's wrong?"

So, he gave up and hid the bundle instead.

When he was about to leave on 5 October 2024, he was given his old clothes which had been ripped five years earlier in the struggle over his initial arrest.

There was a tear in the lining of his jacked and he quickly dropped the notes inside before a guard could see him.

Radalj said he thinks someone told the prison officers of his plan because they searched his room and questioned him before he left.

"Did you forget something?" the guards asked.

"They trashed all my belongings. I was thinking they're gonna take me back to solitary confinement. There will be new charges."

But the guard holding his clothes never knew the secret journal had been slipped inside.

"They were like, 'Get out of here!'. And it wasn't until I was on the plane, and we had already left, and the seat belt sign was switched off, that I reached into my jacket to check."

The notes were still there.

Life After Prison

Courtesy Matthew Radalj

Courtesy Matthew RadaljJust before he had boarded the plane in Beijing a policeman who had escorted him to the gate had used Radalj's boarding pass to buy duty free cigarettes for his mates.

"He said don't come back to China. You're banned for 10 years. And I said 'yeah cool. Don't smoke. It's bad for your health'".

The officer laughed.

He arrived back in Australia and hugged his father at Perth airport. The tears were flowing.

Then he got married to his long-time girlfriend and now they spend their days making candles and other products.

Radalj says he is still angry about his experience and has a long way to go to recover properly.

But he is making his way through the contact list of his former inmate friends – "I have spent the best part of six months contacting their families, lobbying their embassies so they might try to do a better job of helping them during their incarceration."

Some of them, he said, haven't spoken to people back home for nearly a decade. And helping them has also helped with the transition back to his old life.

"With freedom comes a great sense of gratitude," Radalj says. "You have a deeper appreciation for the very simplest things in life. But I also have a great sense of responsibility to the people I left behind in prison."