Ken v Tony: How London elected its first mayor

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRegional mayors are now commonplace in England: Andy Burnham in Greater Manchester, Ben Houchen in the Tees Valley and Tracy Brabin in West Yorkshire are all well-known spokespeople for their areas.

But the most prominent directly-elected mayor in Britain was also the first: London.

As is fitting for a city as exciting as London, the first election for that coveted position included allegations of betrayal, stitch ups and intrigue – and one candidate ended up in prison.

Twenty five years ago Tony Blair's government, elected in 1997 and known as New Labour, was very keen on a new form of devolution.

They wanted mayors like those in America, big personalities elected with powers and budgets (but not too many powers, or too big a budget).

In the end, only one was created by Blair's government.

The 1998 Greater London Authority referendum, held in May that year, asked whether there was support for creating a Greater London Authority with a directly elected mayor and Assembly.

The voters were less keen than New Labour - just 34% turned out to vote, but the majority was clear nonetheless: 72% in favour.

The 'Yes' vote won in every London borough, with support lowest in Bromley with 57% and highest in Haringey with 84%.

PA Media

PA MediaNow London was to have a mayor, who would it be?

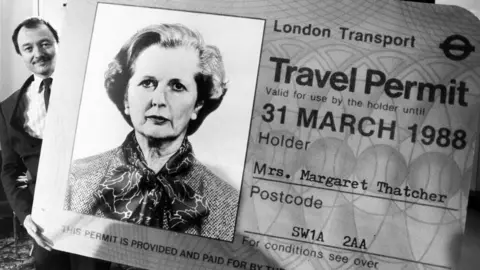

The obvious candidate was Ken Livingstone, the former left-wing firebrand (and publicity-friendly) leader of the Greater London Council (GLC), who went toe-to-toe with the Thatcher government - and lost.

The GLC was abolished in 1986, leaving London in the unenviable position of having 32 boroughs (and the City of London) but no overall strategic elected body for the largest city in Europe.

However, Livingstone's ability to alienate prime ministers wasn't confined to Conservatives.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTony Blair was also not a Ken fan.

"Red" Ken, as he was known, was Old Labour, not New Labour.

The message from Downing St was clear: Stop Ken.

The party management tried to get the very popular Mo Mowlam to stand, then switched to Frank Dobson.

A bearded, avuncular figure who was serving as New Labour's first health secretary, he was 'persuaded' to stand against his old comrade Ken.

Dobson had initially, and somewhat bravely, declared his desire to remain at health, but then had to give up his cabinet seat to run for a job he didn't want.

The internal workings of Labour can be difficult for outsiders - and many insiders - to navigate.

In this case, an electoral college was mandated which led to the popular Livingstone not winning selection.

The vote was a third each for party members, trade unions and London MPs and other elected representatives.

In the final ballot Livingstone won 60% of party members and 72% of affiliated unions, but Dobson won 86% of MPs, MEPs and Greater London Assembly candidates.

Dobson therefore won a narrow overall victory, and the Blairites were accused of rigging the whole thing to keep Old Labour Ken from the nomination.

Livingstone for his part had promised not to run as an independent, then decided that that was what he was going to do after all.

PA Media

PA MediaThe Tories also had a colourful time choosing their candidate.

In September 1999 the novelist Jeffrey Archer was selected by party members, beating Steve Norris.

But in a plot twist reminiscent of one of his books, Archer withdrew from the race a few months later after it was alleged he had committed perjury in a famous libel case.

Lord Archer had secured the Conservative nomination with backing from former prime ministers Margaret Thatcher and John Major, who in 1992 had made him a peer.

Five years earlier, in 1987, Archer had won a libel case against The Daily Star which published a story that he had paid off a sex worker called Monica Coghlan.

After his selection as a mayoral candidate, a former friend of Archer's told the News of the World that he had lied in the libel trial and asked him to provide a false alibi.

Archer stood down from the race, and starred in a production of his courtroom play, The Accused, in London's West End while waiting for his trial to start.

In July 2001 he was found guilty and spent two years in jail, but retained his peerage and membership of the House of Lords as there was no mechanism to remove them at the time.

PA Media

PA MediaNorris was selected as the Conservative Party candidate to replace Archer.

A very different type of Tory, Norris advocated for gay rights and had a relaxed approach to monogamy.

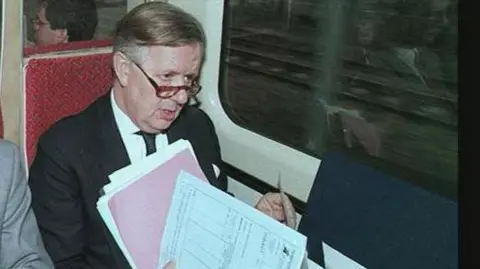

He was also a former transport minister who was obsessed with buses.

In that role, he had a hand in approving the Jubilee line extension from Green Park to Stratford, and the privatisation of London's bus services.

In the rough and tumble world of turn of the century politics, he was given the nickname "Shagger".

A brief snippet from a Guardian profile piece published during that first mayoral campaign gives a flavour of Norris' complex appeal.

"The day his original candidature was announced was marked by a letter to the Times from his father-in-law, a retired rear-admiral, expressing astonishment at Norris's public plans to marry the fourth of his famous five mistresses … since as far as the rear-admiral knew, Norris was still married to his daughter."

Norris was a self-made man, a millionaire car salesman who grew up in working class Liverpool, attending the same school as Paul McCartney.

Not many 2025 Tories can boast that sort of hinterland.

PA Media

PA MediaThere may have been some intrigue in the Lib Dem selection process, but it is lost to history if there was.

Their candidate was the estimable Susan Kramer, who was subjected to condescension and mansplaining throughout the campaign - this was a time when female Labour MPs were referred to as "Blair's Babes" by tabloid and broadsheet newspapers alike.

Livingstone was to mount the first - and so far only - successful independent bid for Mayor of London.

Dobson ran a campaign that never really captured the imagination of London's voters, and his old comrade won the historic poll despite a late surge in support for the Tory candidate.

The May 2000 election was a disaster for New Labour: Dobson got just 13% of the vote and was eliminated in the first round along with Susan Kramer, who polled a respectable 11.9% for the Lib Dems.

Livingstone led by 39% to 27% of first preference votes and polled a total of 776,427 votes to 564,137 for Norris, after second preferences were calculated.

It was a bloody nose and a notable defeat for the previously unassailable Tony Blair.

The BBC News website has an archive of reports from this election, a time capsule of the way politics used to be.

It reported that Dobson's "humiliation in the mayoral poll was underlined as he came fourth in the mayoral contest in Barnet and Camden - the seat which includes his parliamentary constituency".

The 2000 election reports reveal Livingstone said he would "fight for the interests of Londoners as mayor, demanding more money from the government and telling ministers they were wrong over plans to partially privatise the London Underground".

London Underground, now part of Transport for London, remains in public hands under the control of the Mayor of London.

It also reported that Blair "made it clear Mr Livingstone would not be allowed to return to Labour after standing against an official party candidate".

Blair was wrong about that: in 2004 Livingstone was the Labour candidate, and he won, again defeating Norris.

Livingstone was his party's standard bearer again in both 2008 and 2012, on both occasions losing to a young Conservative contender called Boris Johnson.

But that's another story.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]