Tracks show flying giants walked with dinosaurs

University of Leicester

University of LeicesterSome of the largest animals to ever take to the air actually spent much of their time on the ground, a new study claims.

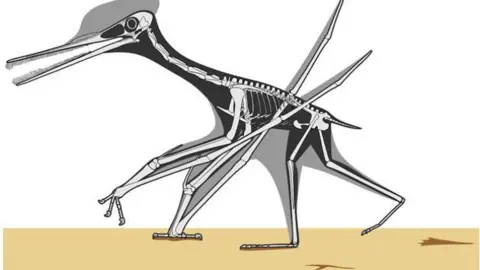

Researchers at the University of Leicester have been examining the tracks left by a type of pterosaur called Quetzalcoatlus, which had a wingspan of up to 10m (32ft).

They believe the quantity and widespread location of their footprints show the creatures began to spend more time on the ground about 160 million years ago and continued to do so until they died out with the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

The team said the tracks offered an insight into the behaviour of these animals which cannot be gleaned from studying the fossilised bones alone.

University of Leicester

University of LeicesterPterosaurs were a group of flying reptiles which existed at the same time as the dinosaurs, but were evolutionarily distinct from them.

By using 3D modelling, detailed analysis and comparisons with pterosaur skeletons, the team said they have matched some tracks with Quetzalcoatlus and others with two separate groups of pterosaurs.

Robert Smyth, a doctoral researcher in the Centre for Palaeobiology and Biosphere Evolution, said: "Footprints offer a unique opportunity to study pterosaurs in their natural environment.

"They reveal not only where these creatures lived and how they moved, but also offer clues about their behaviour and daily activities in ecosystems that have long since vanished."

University of Leicester

University of LeicesterHe said footprints of Quetzalcoatlus have been found in both coastal and inland areas around the world, supporting the idea these long-legged creatures not only dominated the skies but were also frequent ground dwellers.

Another group of pterosaurs, ctenochasmatoids, which are known for their long jaws and needle-like teeth, mostly left tracks in coastal deposits, indicating they waded along muddy shores or in shallow lagoons, using their specialised feeding strategies to catch small fish or floating prey.

Fossilised tracks were also matched to a third group, dsungaripterids, which had powerful limbs and jaws, with toothless, curved beak tips.

These were designed for prising out prey, while large, rounded teeth at the back of their jaws were perfect for crushing shellfish and other tough food items.

Mr Smyth added: "Tracks are often overlooked when studying pterosaurs, but they provide a wealth of information about how these creatures moved, behaved, and interacted with their environments.

"By closely examining footprints, we can now discover things about their biology and ecology that we can't learn anywhere else."

Follow BBC Leicester on Facebook, on X, or on Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected] or via WhatsApp on 0808 100 2210.