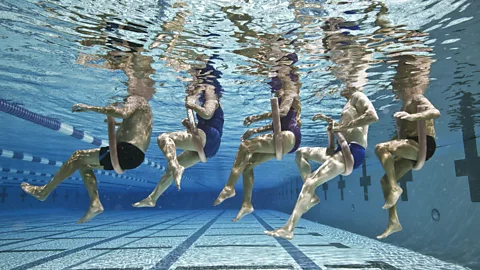

Parasites and Staphylococcus: How hygienic are public swimming pools really?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFrom tropical parasites to bacterial pathogens, here's what else might be swimming in the water.

It might just serve as a way to pass a rainy afternoon, but swimming may be one of humans' oldest hobbies. The earliest swimming pool dates back to 3000 BCE, in the Indus Valley.

Much later, in the 19th Century, swimming pools emerged in Britain and the US. But along with them came the challenge of keeping them hygienic. Even now, public – and private – swimming pools can become hotbeds of infection if they're not well maintained.

Swimming is considered highly beneficial for most people – providing a full-body workout and cardiovascular boost, while being low impact on the bones and joints. However, on rare occasions swimming pools have been linked with outbreaks of gastrointestinal and respiratory illness. Even in well-maintained pools, chlorine tends to be doing more to protect us than we might want to know.

So, just in time for the season of summer swimming (in the northern hemisphere, at least), here's what else might find its way into the pool water with you.

Which bacteria do we swim alongside?

Over the last 25 years, swimming pools have been the most common setting for outbreaks of waterborne infectious intestinal disease in England and Wales. And the biggest culprit is Cryptosporidium.

This parasite can cause a stomach bug that can last for up to two weeks. People can experience diarrhoea, vomiting and abdominal pain – and around 40% will have a relapse of symptoms after the initial illness has resolved.

But most of the time, enteric diseases (the ones that cause diarrhoea and vomiting) clear up on their own in healthy people, says Jackie Knee, assistant professor in the London School of Tropical Medicine's Environmental Health Group. However, they can be a bigger concern for young children, the elderly and people who are immunocompromised, she adds.

Swimmers can catch cryptosporidium when an infected person has a faecal accident in the pool, or from swallowing residual faecal matter from their body, Knee says.

"And they could still shed [the parasite] afterwards, when they're not experiencing symptoms anymore," says Ian Young, associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University's School of Occupational and Public Health in Canada.

You may go to many lengths to avoid swallowing pool water, but evidence suggests that some still ends up in our bodies.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne 2017 study conducted at public swimming pools in Ohio involved testing the blood of 549 people, including adults and children, after swimming in pool water for one hour. On average, the adults swallowed around 21 mL per hour, while children swallowed around 49 mL per hour.

When swallowed, the chances of this water being an infection risk differs depending on how busy the pool is. One study found that contracting cryptosporidium is more likely when swimming at peak times. The researchers tested water from six pools once a week for 10 weeks in summer 2017, and detected cryptosporidium in 20% of the pool samples, and at least once in each pool. Two thirds of these water samples were during the pool's busiest times, in the school holidays.

But cryptosporidium isn't the only thing to watch out for, says Stuart Khan, professor and head of the School of Civil Engineering at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Infections from opportunistic bacteria, such as Staphylococcus, can infect the skin, he says, and there is also the potential to contract fungal infections in swimming pool changing rooms, since these pathogens survive longer in warm, damp environments.

Another common bacterial infection that can be contracted from swimming pools is swimmer's ear, says Khan, which is usually caused by water that stays in the outer ear canal for a long time. However, this isn't spread from person to person.

Although uncommon, the acanthamoeba group of parasites also live in water and can cause eye infections, which are very serious and can cause blindness, says Khan.

It's possible to contract infections through inhalation, too. For example, legionella bacteria may be present in swimming pools. When breathed in through air droplets, can cause the lung infection Legionnaires disease.

However, outbreaks of most infectious diseases linked to swimming pools are rare. "We don't see too many outbreaks of waterborne illnesses in public swimming pools, which means it's done well enough a lot of the time with chlorine disinfection, but occasionally have some outbreaks happening," says Young.

How are bacteria managed in swimming pools?

Before the 1900s, swimming pools didn't have a chemical disinfectant. Some filtered or changed the water frequently, while some pools were built on a slope to help drainage, or fitted with a type of gutter to scoop away visible impurities.

"Traditionally, public bathing sites were either in the ocean where the water was naturally refreshed, or fresh water like a river where there's tidal movement," says Khan.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's thought that the first use of chlorine in the US was in 1903 in a pool at Brown University in Rhode Island, after the chemical had been developed as a drinking disinfectant.

In rare cases, it's possible to get bacterial infections from swimming pools, such as from pathogens including Campylobacter, Shigella and Salmonella. In most cases these bacteria cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea and stomach cramps, as well as fever. However, they can also lead to serious complications. Thankfully, much of the risk is mitigated by chlorine, says Khan.

Viruses such as norovirus – which can lead to diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting and stomach pain, among other symptoms – are a little tougher than most bacteria. There have been isolated reports of outbreaks at swimming pools, however these are usually associated with the failure of equipment or chlorine levels that are too low. The virus is generally well killed with chlorine, says Khan.

In order to maintain this level of protection against viruses and bacteria, a pool must be well controlled, says Khan. This involves ensuring that the water is the right pH and alkalinity to allow the chlorine to be effective, he adds.

Also, the amount of chlorine required depends on how many people are in the pool at any given time. "The higher the chlorine demand, the more you need to put in. There's quite a science to it," Khan says.

Regulations around public swimming pool maintenance differ between countries. In the UK, there are no specific health and safety laws, but operators must comply with the Health and Safety at Work Act. In the US, swimming pools can be regulated at both federal and state level. While the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a health and safety code for pools, it is voluntary.

But even in well maintained pools, cryptosporidium is resistant to normal chlorine levels.

"The cryptosporidium parasite is extremely tolerant to chlorine," says Knee. "Most other pathogens are killed within minutes, but cryptosporidium stays alive and active for more than a week at normal levels of chlorine treatment."

This is because of how the parasite is structured. "It can go into spore formation, where it wraps itself up tightly and prevents anything touching the exterior, which makes it resistant to lots of things," says Khan.

The risk of infection is likely highest from bigger and more obvious accidents in the pool, but this risk can be mitigated if responded to immediately, says Knee. Pool operators can either use a coagulant and filter the pool water – if they have an appropriate filtration setup that doesn't filter the water too quickly – or use 'super chlorination', Knee says. The latter involves adding much higher levels of chlorine to the water and leaving it for a longer period of time.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut while these incidents are pretty obvious, people can shed faecal material passively without it being a massive event, Knee says.

Are there other risks in the pool?

You may be surprised to learn that the unmistakable smell of chlorine that hits you when you come out of the changing room and into the swimming pool actually isn't technically the smell of chlorine.

"This smell is when chlorine is reacting to other materials, particularly ammonia, in the water, which comes from urine and sweat," Khan says. This ammonia reacts with chlorine and forms chloramine, which is what causes the smell.

Swimming in other environments

With so many unwanted guests washing around the water of swimming pools, it might be tempting to consider wild swimming instead – perhaps a spot of bathing in a lake, river or the sea. But there are well-documented infection risks here too. Some water bodies contain untreated sewage, for example, or they can be contaminated with animal faeces.

"So, the smell suggests that there are bodily fluids in the pool reacting with the chlorine," says Khan.

These chloramines hover above the surface of the water and inhaling them can cause irritate our throats and eyes, says Young. "Chemicals that cause irritations and degrade the quality of chlorine in the pool can affect everyone's health," he says. "Just a short amount of exposure can affect you."

There is a very small body of research suggesting that people continuously exposed to chloramine, such as swimming teachers and lifeguards, could be at increased risk of developing asthma.

What can be done to minimise your risk when swimming?

The risk of chloramines forming above the water can be lowered by ensuring that everyone showers before entering the pool, says Yong, which helps to wash off faecal matter. Showering can help to lower the risk of spreading and contracting infection, says Knee.

Yong also emphasises the importance of a pool having good ventilation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOther important ways to avoid infections from swimming pools include avoiding swallowing pool water, says Knee – as the pathogens that cause diarrhoea are transmitted by ingesting water contaminated with poo.

Knee adds that it's important to quickly alert pool operators to contamination events and exit the pool immediately.

The CDC suggests that those with pools can lower the risk of infection by regularly draining and replacing water, maintaining chlorine and pH levels within certain ranges, as well as scrubbing the pool surfaces to remove any slime.

On balance, Knee and Khan both agree that the health and social benefits of swimming outweigh the risk of infection.

"Properly maintained pools that are properly treated and have operators who know how to jump into action when there is a contamination event pose minimal risk to health, in terms of infectious disease risk," Knee says.

So, there are plenty of reasons to take a dip this summer – just make sure you take a shower, too.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.