These countries don't fluoridate their water – here's why

Getty Images

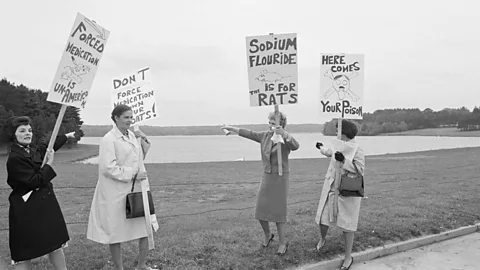

Getty ImagesWith water fluoridation of drinking water under the spotlight in the US, we look at why some countries choose not to add the mineral to supplies while others have repealed the practice.

Opposition to fluoride is spreading. The mineral was there, in the recent "Make America Healthy Again" report on childhood disease, among a long list of factors blamed for a crisis of chronic disease afflicting children in the United States.

Wellness influencer Calley Means, who is now an adviser to the US government, has called drinking water fluoridation an "attack on lower income kids" and suggested that parents should throw out their children's toothpaste if they find it contains fluoride. His views on fluoride appear to align with those of Robert F Kennedy Jr, the US Health and Human Services Secretary. His sister, Casey Means, is also Donald Trump's nominee to serve as the US Surgeon General.

Yet, ever since scientists noticed that people had lower rates of tooth decay in areas with naturally higher levels of fluoride in the water, in some areas it has been added to drinking water in an effort to improve dental health.

At the end of March 2025, however, Utah became the first US state to ban the use of fluoride in the public water supply. In early May, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed a bill into law that bans "certain additives" in the water system, which would include fluoride – ending a practice that dates back to 1949 in the state. And in April, Kennedy Jr announced that he would direct the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to recommend against fluoridating water and the Environmental Protection Agency is holding an urgent review of the scientific evidence on any potential health risks of adding fluoride to water.

Many scientists consider community water fluoridation to be a public health victory – one that has resulted in lower rates of dental decay and better oral health overall for millions of people worldwide. Some recent reviews of the evidence have suggested that the beneficial effects may not be as pronounced as they were 50 years ago before fluoride in toothpaste was widely available – although they still find a benefit. A 2016 review of fluoridation in Australia, for example, found that water fluoridation reduced dental decay in children's first teeth by about 35%, while a 2022 health monitoring report for England also found that it reduced tooth decay in 3-year-olds by 35%. This effect is greatest for children living in more deprived areas, who may have less access to dental care or even to regular tooth-brushing with fluoride at all.

First introduced in the city of Grand Rapids in the US state of Michigan in 1945, community water fluoridation today is practised in about 25 countries, including parts of the UK, Spain, Ireland, Singapore, Malaysia and Brazil. In total, fluoridated drinking water reaches more than 400 million people worldwide.

In the US, approximately 63% of the population – 209 million people – receive fluoridated water. For nearly 12 million of those people, the mineral is not added, but occurs naturally in the water supply.

One argument put forward against fluoridation is that some studies have linked fluoride exposure to slightly lower average IQ scores in children, as outlined in a 2025 meta-analysis – a type of study that combines the results of several other studies – of the research. Detailed reviews of the evidence, however, have concluded that this association occurs when the levels of fluoride are twice the recommended limit in the US and scientists have found significant methodological and statistical issues with the 2025 meta-analysis.

Those opposed to artificial drinking water fluoridation also often point to the fact that most countries around the world don't add the mineral to water. But is that true? And, if it is, why don't those countries fluoridate their water – and what have the outcomes been?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFluoride is a naturally occurring mineral, thought to help prevent tooth decay by strengthening the hard outer layer of teeth, known as enamel, and replacing the minerals lost from our teeth from the acid produced when we eat. Many people apply it topically (for example with a toothpaste). However, studies suggest that a more continuous, systemic, low-dose exposure – such as through drinking water – can be especially effective in children, whose bones and teeth are still forming. One 2019 review of 32 studies, for example, found that children who lived in areas with fluoridated water tended to have lower levels of tooth decay – also known as dental caries – than those who didn't.

"The difference between a toothpaste and water is that, assuming that people drink water during the day, they have a constant exposure to fluoride at a very low concentration," says Vida Zohoori, professor in public health and nutrition at the UK's Teesside University who focuses on researching fluoride and a co-author of the International Association for Dental, Oral and Craniofacial Research (IADR) 2022 guidelines on community water fluoridation. "The benefit comes from constant exposure to low levels of fluoride."

This is especially noticeable for children from more socioeconomically deprived backgrounds.

"Community water fluoridation is to close the gap between poor and well-off people," says Zohoori. "It reaches everybody – the whole population, not just specific people – so it reduces general health inequality." She points to the difference between the town where her university is located, Middlesbrough, in Yorkshire in the north of England, versus the neighbouring town of Hartlepool. Both communities are socioeconomically disadvantaged. But Hartlepool's water has naturally occurring levels of fluoride of up to 1.3mg/L, while Middlesbrough does not. "Middlesbrough is one of the counties with the highest levels of tooth decay in children, whereas Hartlepool has much less," she says. In March, England's Department of Health and Social Care recommended expanding community water fluoridation to areas of north-east England, including Middlesbrough.

Too much fluoride can also be a problem, though. More than 1.5mg of fluoride per litre has been found to potentially cause dental fluorosis, usually a cosmetic condition that gives teeth white spots. And more than 6mg/L can cause skeletal fluorosis, a serious bone condition that can be crippling. As a result, WHO guidelines recommend that drinking water contains no more than 1.5mg/L of fluoride. In the US, the Public Health Service recommends up to 0.7mg/L while water companies that fluoridate water in England are asked to keep concentrations under 1.0 mg/L.

Concerns around excessive fluoride intake are one reason why some countries have chosen not to artificially fluoridate their water supplies – but only because their drinking water already has naturally high levels of fluoride.

Fluoride occurs in soil, plants and water. Some types of rocks and soil have higher concentrations than others. "It really comes down to geochemistry," says Joel Podgorski, a senior scientist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Dübendorf, Switzerland. "Certain lithologies have more of these fluoride-containing minerals." In particular, he notes, igneous rocks, such as those formed by lava, tend to contain more fluoride.

The presence of rocks containing fluoride can raise fluoride levels in groundwater. In Italy, for example, fluoride concentrations in water range from around 0.1 to 6.1 mg/L – but in areas with volcanic rock, fluoride levels can reach up to 30.2 mg/L. In some areas, such as Lazio or Calabria, fluoride is actively removed, or water is diluted in order to keep public supplies below the 1.5mg/L limit recommended by the WHO and the EU, says Tommaso Filippini, associate professor of epidemiology and public health at Italy's University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. Filippini has authored several papers on fluoridation.

But there are a variety of other reasons that countries don't fluoridate their water supplies.

In Europe, a 2018 report found that, of 28 EU nations, only Ireland, parts of the UK and Spain currently fluoridate their water supplies. Eleven countries had done so in the past but stopped. Fourteen never started.

However, countries that ceased water fluoridation programmes did not say that they did so because authorities there were concerned about public safety, says lead author Mary Rose Sweeney, a public health researcher who at the time of publication was working at Dublin City University in Ireland and now works at Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and is vice president of the European Public Health Association's nutrition section.

Instead, some countries cited public complaints, such as from people who thought it was a violation of their human rights, or said it was up to individuals to manage their own fluoride intake. Others pointed to the fact that their populations got enough fluoride elsewhere. Of 11 countries that had ceased their fluoridation programmes, only two cited questions about safety and efficacy – Finland said fluoride's efficacy hadn't been proved, while the Czech Republic cited "debates" about fluoridation's safety and efficacy. None said they stopped fluoridation because they had determined that fluoride was harmful.

For some of those populations, fluoride was naturally available in drinking water but for others, certain food and drink products contained fluoride. According to the 2018 report, Bulgaria fluoridated its milk while Greece added the mineral to bottled water.

These differing approaches to fluoridation exist outside the EU as well, says Zohoori, who is currently leading a study comparing national fluoridation schemes in Brazil, the UK, Colombia, and Chile. "Some countries, like Switzerland, have fluoridated salt," she says. "Brazil has fluoridated water; Colombia, fluoridated salt; Chile, fluoridated milk."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA 2012 review of Asian countries found that countries that chose not to fluoridate their water typically did so for one of three reasons: high naturally occurring levels of fluoride (as in parts of India); technical or financial barriers (such as in Nepal); or because fluoride was provided to communities in other ways.

Take Thailand, which doesn't fluoridate its water but which has the world's largest milk fluoridation program. Milk fortified with 2.5mg/L of fluoride is provided to more than one million children daily, for free, in public schools. Children also receive fluoridated milk during the school holidays. Thailand's programme includes oral health education, check-ups, fluoride varnish – a fluoride-containing varnish applied to the teeth, usually by a dentist – and supervised tooth-brushing sessions with fluoride-containing toothpaste. One study found that, at a cost of just THB 11.88 ($0.40) per child, per year, this approach reduced the prevalence of children's dental caries by more than a third.

Meanwhile, salt fluoridation is the second most common way that countries deliver the mineral to their populations, after drinking water fluoridation, according to a 2018 review. The first country to add fluoride to salt was Switzerland. Table salt there has contained fluoride since 1955.

Like milk fluoridation, salt fluoridation is effective at reducing tooth decay, but less so than water fluoridation. Fluoridated salt contributes around 0.5-0.75mg of fluoride to a person's intake per day, on average, while adults need about 3mg daily.

Zohoori says salt might not be the best option overall. "As a nutritionist, I don't want to promote the consumption of salt," she says. "To me, fluoridated water is the best method."

Access to dental care can also influence countries' decisions to fluoridate water. One 2015 study found huge disparities in access to dental health care – generally tied to better oral health – between the US and a selection European countries. In five of the 10 European countries surveyed, more than 75% of respondents had dental coverage. That included 98% of respondents in Germany, 96% in the Czech Republic, and 92% in Denmark. In the US, just 48% had dental coverage, in comparison.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStill, Zohoori urges care when looking at the relatively low levels of water fluoridation in Europe as a reason to stop doing it elsewhere. Europe, she points out, doesn't have a great dental health record. A 2023 WHO report found that Europe had the highest prevalence of major oral disease, including the most caries in permanent teeth, of any region in the world. More than one in three adults had dental caries.

"Across the 28 EU countries, the cost of dental caries is higher than for Alzheimer's, cancer [or] stroke," says Zahoori. "Caries are the third-costliest health issue overall – behind just diabetes and cardiovascular disease."

In Japan, drinking water supplies are not artificially fluoridated, but the mineral is distributed to the public through other means, such as fluoride mouth-rinses in schools in many prefectures.

Some researchers argue that Japan should consider changing its policy on drinking water fluoridation. A 2023 study of nearly 35,000 children, which followed them between the ages of five and a half to 12, found that four out of every 10 seven-year-olds had had dental treatment for caries in the previous year alone. That's a high proportion given that children in Japan, on average, consume less sugar and fewer sweets than their European peers.

Researchers also found that children in Japan who lived in areas with more naturally occurring fluoride had fewer caries. Each 0.1 part per million increase in fluoride concentrations correlated with a roughly 3.3% reduction in the prevalence of caries. "This finding suggests the possibility to reduce dental caries through fluoride utilisation at a population level in Japan," the study authors wrote.

While some countries such as the US debate removing fluoride from water, other regions, notably, have taken such a step only to reverse it. A famous example is Calgary, Canada, which stopped fluoridating its local water supply in 2011 – and then, after a rise in tooth decay there, decided to reinstate fluoridation earlier this year.

"At the end of the day, if fluoride is removed from water, it will be another health inequality. It will be the disadvantaged communities who will disproportionately feel the effects," Sweeney says.

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.