Scars from the world's first deep sea mining test 50 years on

USGS

USGSPresident Donald Trump is trying to fast track new deep sea mining efforts, but half a century after the world's first deep sea mining tests picked mineral-rich nodules from the seafloor off the US east coast, the damage has barely begun to heal.

Plunging to the ocean's abyss on the Blake Plateau, a deep-sea mountain range off the coast of North Carolina, is an otherworldly experience. It's like no other ocean bed that microbiologist Samantha Joye has ever visited. In her deep-sea submersible called Alvin – a three-person vessel made of titanium thick enough to withstand pressure in the ocean's depths, with two robotic arms reaching outside for sample collection – it takes more than an hour to descend to about 2,000m (6,600ft) below the water's surface.

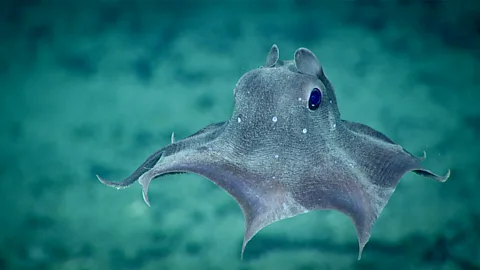

On the way down, the water is on fire with bioluminescence and abounds with wildlife. There are huge fish, small fish and jellyfish. Shrimp, sea slugs, octopuses and hundreds of squid bump into the submarine, seeming to be curious about its free fall into their home.

"I have worked all over the place, and my mind was blown on the Blake Plateau. I mean, it's just spectacularly diverse," says Joye, recalling her last trip to the plateau in August 2018. At touchdown, the silty floor is covered in worms, sponges, stars and mussels the size of an adult human's forearm, says Joye, gesturing to her own limb to show me.

Among the abundance of life, though, a section of the Blake Plateau is barren with the scars from the world's first deep-sea mining pilot test carried out in 1970. That experiment 50 years ago was just a proof-of-concept, but full-scale commercial deep-sea mining is on many of today's national to-do lists. In April 2025, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order to fast-track deep-sea mining.

The traces of those first rudimentary tests on the Blake Plateau are still visible today, half a century on, and scientists think they're just a small example of the effects deep-sea mining could have on the ocean ecosystem if it were to be conducted at scale.

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and ResearchThe world's first deep-sea mining test was conducted by US company Deepsea Ventures in July 1970. A vacuum-cleaner-like machine bulldozed through the abyss and sucked up 60,000 baseball-sized lumps off the bottom of the ocean. The nodules – filled with manganese, nickel and cobalt that accumulate a few millimetres per million years – were hoped to become a resource for the nation's industrial endeavours. There remains high interest in them today, as they're replete with minerals for making batteries for electric cars and smartphones, as well as medical and military technology.

Deepsea Ventures' project fell through, and no more deep-sea mining was done off the US East Coast. But a remote-controlled robot sent to that segment of the Blake Plateau during a 2022 scientific expedition found the company's footprints. Scientists snapped pictures of defined dredge lines in the mud for more than 43km (27 miles). The lines dug into the abyss like train tracks, as if somebody had raked through it just recently, and the damage was "widespread and definable", according to reports. Where the tracks are, there is nothing: no nodules and no biodiversity. No curious squid. Nothing like the kaleidoscope of beauty Joye encountered in 2018, just around the corner.

While no data is available on what that part of the Blake Plateau looked like before the deep-sea mining experiments in the 1970s, the contrast between the desolate scraped mud tracks and the rest of the Blake Plateau is stark. (You can see these tracks in the image at the top of this article.) The site is a proxy for what might happen elsewhere, says Joye.

Before and after data from a mining simulation in an analogous area in the Pacific Ocean, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, south-east of Hawaii and poised to be a deep-sea mining hotspot, suggests these ecosystems take hundreds of years to bounce back. Segments there that had been test-ploughed through in 1989 had much lower diversity of large animals, especially filter feeders, and still had up to just half of their microbial communities after 26 years.

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and Research"And if you were thinking about something that was going to recover pretty quickly, it would be microbes, right?" says Joye. "And that was essentially a controlled experiment supposed to do minimal damage." Research from March 2025 confirmed the findings, noting that despite some recent recolonisation of the area, the impacts likely last for decades.

The Metals Company and Impossible Metals, two players currently active in the field, say their machines are now much more sophisticated, sustainable and less invasive than those from the pilot test half a decade ago. Impossible Metals, for instance, aims to pick up nodules one by one, "delicately", their reports say, without raking the seabed. Impossible Metals has already placed a request for a lease for exploration and mining off the coast of American Samoa.

"All mining has impacts. We have invented new technology to minimise the impacts," says Impossible Metals chief executive Oliver Gunasekara. He notes mining today is carried out in some of the world's most biodiverse areas, like the Indonesian rainforest, which is mined for nickel. As part of any mining permit approval, an environmental impact assessment would be performed to understand the impacts and "make sure they are acceptable", says Gunasekara.

Yet, researchers already think there are dozens of possible effects on the seabed. And precisely forecasting the impacts of deep-sea mining is difficult because so little is known about these sprawling underwater ecosystems – with more than 70% of the world's waters still unmapped, says Christopher Robbins, associate director of Ocean Conservancy. In 2023, researchers suggested that about 90% of species in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, are new to science: they found more than 5,000 deep-sea creatures they'd never seen before.

In 2024, scientists discovered the world's largest deep-sea coral reef on the Blake Plateau: more than 83,000 individual coral mound peaks spanning 500km (310 miles) in length and 100km in width (60 miles), all the way from the coast of South Carolina to the tip of Florida. The researchers from the US' National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) who discovered the coral reefs told the BBC they were not available to discuss the work at this time.

Since more than 20 different pharmaceuticals have been developed thanks to organisms discovered in the deep sea, many undiscovered concoctions could be lost to deep-sea mining before even being discovered.

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and ResearchPlus, the abyssal plain is not the only ecosystem at risk, says Robbins. The mining machines trawling through the ocean bed release waves of sediment from the ground, and discharge mining wastewater from the vessels on the surface, cycling abyssal debris in plumes that can travel large distances into the water column. Research shows the plumes could mess with the lifestyle, reproduction and feeding of organisms living in these areas. Studies suggest they can stress out jellyfish's mucus production and make it hard for organisms to communicate via bioluminescence, or clog fish's airways and end up in their diet.

It’s unclear what impact this will have on the ocean's ability to capture carbon, Robbins says. Species living in the dark zone above the abyss but below the surface are responsible for drawing down upwards of six gigatons of carbon, which is about 14% of the carbon that humans emit into the atmosphere each year, says Robbins. (The vacuuming vehicles could also be releasing more than 172 tonnes of carbon directly from the seabed every year for every square kilometre mined, according to Planet Tracker.)

Aside from the wildlife impact, deep-sea mining in US waters can have some substantial impacts on the fishing industry, according to Robbins's recent report on potential conflicts in both oceans. "There are just too many unanswered questions that require us to take a step back to allow the fishing industry, frankly, to be better informed about the trade-offs," says Robbins.

Off the US West Coast, another study from 2023 suggested that the migration routes of bigeye, skipjack and yellowfin tuna could overlap with potential sediment plumes if commercial mining were to be unrolled. Other research has suggested that small developing countries catch as much as 10% of their tuna from areas likely affected by deep-sea mining.

The Blake Plateau, still scarred from the 1970 mining experiment, is likely not a target for deep sea mining yet, says Gorka Sancho, a fish ecology expert at College of Charleston, who penned a petition letter to President Joe Biden in 2024 calling for robust long-term protections of the Blake Plateau. In 2020, Trump issued a moratorium banning drilling and mining in waters off the US south-east coast until 2032. "But everything can change on a dime these days," says Sancho.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone, on the other hand, is where miners have set their targets. Studies suggest this area alone contains more nickel, cobalt and manganese than all of the deposits on land.

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and ResearchIn April 2025 Trump signed an executive order to fast-track deep-sea mining called Unleashing America's Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources. Some days later, the government received a request for license to explore and to mine from the Canadian firm The Metals Company, including areas outside the US's jurisdiction. If the US granted such a permit, this could be in conflict with the international framework governing international waters and the seabed, known as the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), according to the ISA's secretary-general Leticia Reis de Carvalho. (It's worth noting, however, that the US has never ratified Unclos.) The BBC contacted The Metals Company for comment but received no response by the time of publication.

Trump's order commits Noaa to expedite mining permits. Robbins comments that the executive order is at odds with Noaa's mission. Noaa told the BBC that the agency reviews applications for compliance and requirements in accordance with the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act and regulations for exploration licenses. "The process ensures a thorough environmental impact review, interagency consultations and opportunity for public comment," Noaa states.

The agency added: "Noaa is committed to an efficient review of applications for exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits in accordance with the statutory requirements governing US seabed mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction and is actively exploring ways to streamline the application process by waiving obsolete requirements, enhancing coordination across agencies and engaging with international and private partners to ensure a transparent, and science-based licensing and permitting framework."

At a congressional hearing about the new legislation, MIT mechanical engineering professor Thomas Peacock stated that some of the impacts of nodule mining "may not be as speculated". His work in 2022, carried out in part on behalf of The Metals Company, showed that only 2-8% of the murky plumes reach 2m (6.5ft) above the seabed and do not settle for hours, but that is just a few milligrams of sediment per litre and "roughly the equivalent of a grain of sand in a fishbowl". Still, Peacock suggested we need further advances in sensor technologies and computational modelling to craft reliable predictions of the impacts of commercial-scale ocean floor exploitation. He also suggested that large off-limit areas will have to be instituted to protect wildlife.

Many nations around the world have called for a moratorium on seabed mining until the risks are fully assessed, the science is clear, and the regulation is in place. More than 900 scientists and policy experts have also signed a letter asking for a delay in commercial activity.

In the meantime, the scars from the US's first foray into deep-sea mining testing are still there on the ocean floor, half a century on. They remain still in time, etched into the abyss, at the bottom of a world swirling with life.

"I see this place as a national treasure. What makes this place so special?" says Joye, reminiscing on her last dive down at the Blake Plateau. "That mystery is something that we need to solve, so that we can serve as stewards of these habitats."

--

Update: This story was updated on 12 May to include a response to the BBC's request for comment from Noaa. It was updated on 19 May to include detail of the 2020 moratorium issued by Trump banning drilling and mining in waters off the US south-east coast.

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.