What your earwax can reveal about your health

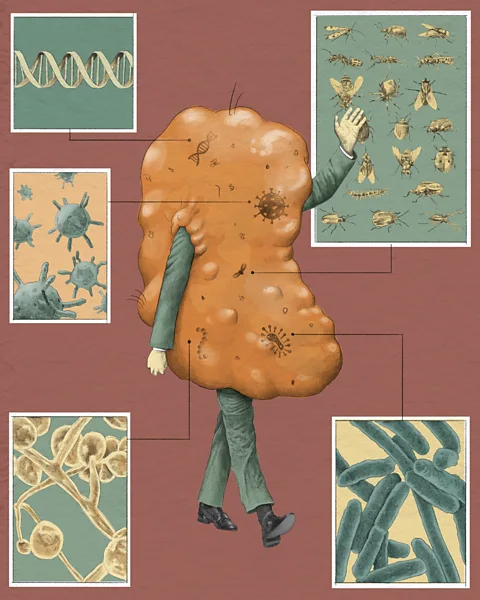

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBCFrom Alzheimer's to cancer, earwax can contain valuable indicators to a person's health. Now scientists are analysing its chemistry in the hope of finding new ways of diagnosing diseases.

It's orange, it's sticky, and it's probably the last thing you want to talk about in polite conversation. Yet earwax is increasingly attracting the attention of scientists, who want to use it to learn more about diseases and conditions like cancer, heart disease, and metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes.

The proper name for the gloopy stuff is cerumen, and it's a mix of secretions from two types of glands that line the outer ear canal; the ceruminous and sebaceous glands. The resulting goo is mixed with hair, dead skin flakes, and other bodily debris until it reaches the waxy consistency we all know and try our best not to think about.

Once formed in the ear canal, the substance is transported by a kind of conveyer belt mechanism, clinging on to skin cells as they travel from the inside of the ear to the outside – which they do at a speed of approximately one 20th of a millimetre every day.

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBCThe primary purpose of earwax is debated, but the most likely function is to keep the ear canal clean and lubricated. However, it also serves as an effective trap, preventing bacteria, fungi and other unwelcome guests such as insects from finding their way into our heads. So far, so gross. And yet, possibly due to its unpalatable appearance, earwax has been somewhat overlooked by researchers when it comes to bodily secretions.

That's now starting to change, however, thanks to a slew of surprising scientific discoveries. The first is that a person's earwax can actually convey a surprising amount of information about them – both trivial and important.

For example, the vast majority of people of European or African descent have wet earwax, which is yellow or orange in colour and sticky. However, 95% of East Asian people have dry earwax, which is grey and non-sticky. The gene responsible for producing either wet or dry earwax is called ABCC11, which also happens to be responsible for whether a person has smelly armpits. Around 2% of people – mostly those in the dry earwax category – have a version of this gene which means their armpits have no odour.

However, perhaps the most useful earwax-related discoveries relate to what the sticky stuff in our ears can reveal about our health.

Important clues

In 1971, Nicholas L Petrakis, a professor of medicine at University of California, San Francisco, found that Caucasian, African-American and German women in the USA, who all had "wet earwax", had an approximately four-fold higher chance of dying from breast cancer than Japanese and Taiwanese women with "dry" earwax.

More recently in 2010, researchers from the Tokyo Institute of Technology took blood samples from 270 female patients with invasive breast cancer, and 273 female volunteers who acted as controls. They found that Japanese women with breast cancer were up to 77% more likely to have the gene coding for wet earwax than healthy volunteers.

Nevertheless, the finding remains controversial, and large scale studies in Germany, Australia and Italy have found no difference in breast cancer risk between people with wet and dry earwax, although the number of people in these countries with dry ear wax is very small.

What is more established is the link between some systemic illnesses and the substances found in earwax. Take maple syrup urine disease, a rare genetic disorder that prevents the body from breaking down certain amino acids found in food. This leads to a buildup of volatile compounds in the blood and urine, giving urine the distinctive odour of maple syrup.

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBCThe molecule responsible for the sweet-smelling wee is sotolone, and it can be found in the earwax of people with the condition. This means the condition could be diagnosed through simply swabbing someone's ears, a much simpler and cheaper process than doing a genetic test. Although such a test may not even be necessary.

"The earwax literally smells like maple syrup, so within 12 hours of the birth of the baby, when you smell this distinct and lovely smell it tells you that they have this inborn error of metabolism," says Rabi Ann Musah, an environmental chemist at Louisiana State University.

Covid-19 can also sometimes be detected in earwax, and a person's earwax can also tell you whether they have type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Early work has suggested that you can tell if someone has a certain form of heart disease from their earwax, although it's still easier to diagnose this condition from blood tests.

There's also Ménière's disease, an inner ear condition that causes people to experience vertigo and hearing loss. "The symptoms can be very debilitating," says Musah. "They include severe nausea and vertigo. It becomes impossible to drive, or to go places accompanied. You eventually suffer complete hearing loss in the ear that is afflicted."

Musah recently led a team which discovered that the earwax of patients with Ménière's disease has lower levels of three fatty acids than that of healthy controls. This is the first time anyone has found a biomarker for the condition, which is usually diagnosed by excluding everything else – a process which can take years. The finding raises the hope that doctors could use earwax to diagnose this condition more quickly in the future.

"Our interest in earwax as a reporter of disease is directed at those illnesses that are very difficult to diagnose using typical biological fluids like blood and urine or cerebral spinal fluid, and which take a long time to diagnose because they're rare," says Musah.

More like this:

But what is it about earwax that makes it such a treasure trove of health information? The key, it turns out, is down to the waxy secretions' ability to reflect the inner chemical reactions taking place inside the body – a person's metabolism.

"Many diseases in living organisms are metabolic," says Nelson Roberto Antoniosi Filho, a professor of chemistry at the Federal University of Goiás in Brazil, who lists diabetes, cancer, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's disease as examples. "In these cases, mitochondria – the cell organelles responsible for converting lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins into energy – begin to function differently to those in healthy cells. They start to produce different chemical substances and may even stop producing others."

Antoniosi Filho's lab have discovered that earwax concentrates this great diversity of substances more than other biological fluids such as blood, urine, sweat, and tears.

"It makes a lot of sense because there's not a lot of turnover in earwax," says Bruce Kimball, a chemical ecologist at the Monell Chemical Senses Centre, a research institute based in Philadelphia. "It kind of builds up, and so there's certainly a reason to think that it might be a good place to capture long-term snapshots of changes in metabolism."

Tricky diagnoses

With this in mind, Antoniosi Filho and his team are developing the "cerumenogram" – a diagnostic tool they claim can accurately predict whether a person has certain forms of cancer based on their earwax.

In a 2019 study, Antoniosi Filho's team collected earwax samples from 52 cancer patients who had been diagnosed with either lymphoma, carcinoma, or leukaemia. The researchers also took earwax from 50 healthy subjects. They then analysed the samples using a method which can accurately detect the presence of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) – chemicals that evaporate easily in air.

The researchers identified 27 compounds in earwax that served as a kind of "fingerprint" for cancer diagnosis. In other words, the team could predict with 100% accuracy whether someone had cancer (either lymphoma, carcinoma, or leukaemia) based on the concentrations of these 27 molecules. Interestingly, the test could not distinguish between different types of cancer, suggesting that the molecules are produced either by, or as a response to, cancer cells from all these types of cancer.

"Although cancer consists of hundreds of diseases, from a metabolic point of view, cancer is a single biochemical process, which can be detected at any stage through the evaluation of specific VOCs," says Antoniosi Filho.

While in 2019 the team identified 27 VOCs, they are currently focusing on a small number of these that are exclusively produced by cancer cells as part of their unique metabolism. In as-yet unpublished work, Antoniosi Filho says they have also shown that the cerumenogram is able to detect the metabolic disturbances that occur in pre-cancerous stages, where cells exhibit abnormal changes that could potentially lead to cancer, but are not yet cancerous.

"Considering that medicine indicates that most cancers diagnosed at stage 1 have up to a 90% cure rate, it is conceivable that the success in treatment will be much higher with the diagnosis of pre-cancer stages," says Antoniosi Filho.

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBCThe research group is also studying whether the metabolic changes caused by the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's could also be picked up by such a device, although this work is in the early stages.

"In the future, we hope that the cerumenogram will become a routine clinical examination, preferably every six months, that allows, with a small portion of earwax, to simultaneously diagnose diseases such as diabetes, cancer, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's, as well as evaluate metabolic changes resulting from other health conditions," says Antoniosi Filho.

In Brazil, the Amaral Carvalho Hospital has recently adopted the cerumenogram as a diagnostic and monitoring technique for cancer treatment, says Antoniosi Filho.

Musah is also hopeful that her research will one day help people suffering from Ménière's disease, a condition for which there is currently no cure. She first hopes to validate her test on a larger sample of patients in the clinic, before producing a diagnostic test that could be used by clinicians in their offices.

"We are currently working on developing a test kit very similar to what you would see in over-the-counter types of kits that you can buy for Covid-19 testing," says Musah.

Understanding earwax

Just the observation that three fatty acids are very low compared to normal earwax may also provide some clues that can be further investigated, Musah explains. "It might help us understand what causes the disease, or perhaps even suggest ways in which it can be treated," she says.

Musah says that a lot of foundational work is still needed to understand the chemical profile of normal, healthy earwax – and how this changes in different disease states. But she hopes that one day it may be routinely analysed in hospitals to diagnose diseases, in much the same way as blood.

"Earwax is a really wonderful matrix to use because it is very lipid rich, and there are lots of diseases that are a consequence of dysregulation of lipid metabolism," says Musah.

Perdita Barran, a chemist and professor of mass spectrometry at the University of Manchester in the UK, doesn't study earwax specifically, but does analyse biological molecules and investigate if they could be used to diagnose diseases. She agrees that, theoretically at least, it makes sense that this substance would be a good place to look for signs of illness.

"The compounds that you find in blood tend to be water soluble, whereas earwax is a very lipid-rich substance, and lipids don't like water," says Barran. "So if you only study blood, you only get half the picture. Lipids are the canary in the coal mine molecules. They're the ones that really start changing first."

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.