'We use them every day': In some parts of the US, the clack of typewriter keys can still be heard

Ernesto Roman

Ernesto RomanComputers and smartphones might be where most writing is done these days, but typewriters still have work to do in the US.

Pretty much every day, another customer clutching an old typewriter will walk into Mike Marr's shop in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Marr carefully looks the machine over. Invariably, it will be a total mess. Made decades ago, the hunk of heavy metal bristling with moving parts is now laced with years of grime. The keys are too stiff. Or maybe the paper that's supposed to glide through it keeps getting stuck.

"Do you think you can get it going again?" the customer will ask, a touch of anxiety in their voice. Marr, who has been repairing typewriters for more than 20 years, will say he'll give it his best shot.

"When they come in and pick that typewriter up, just seeing their smile is everything to us," he says. Even in the year 2025, a century and a half after the first commercially successful typewriter was introduced to the American public, surprising numbers of people in the US are still using these machines. And not just for fun – many of Marr's customers are businesses. "We're still servicing probably 20 to 25 typewriters a week," he says. He employs three other people in his shop to keep up with the demand. "Isn't that crazy?"

In today's world, internet-connected computers and smartphones are king. They're used for the vast majority of business tasks and transactions. But here and there, in little offices and warehouses, you can still find a well-worn typewriter lingering in the corner. A machine whose keys have been pressed many thousands, if not millions, of times. To this day, typewriters print names on forms. They put addresses on envelopes. They fill out cheques. And the people who use them, generally speaking, have no intention of switching to a computer any time soon – at least for those particular tasks.

It was back in 1953 that Marr's grandfather founded the business he now runs: Marr Office Equipment. Decades ago, a call came through from IBM. The tech giant was looking for a new typewriter distributor in the northeast of the US. Marr's father and uncle, in charge at the time, were over the moon. "That was the biggest thing that could ever happen to them," says Marr. "Trailer trucks would just pull up and unload IBM after IBM. They'd already be sold. We couldn't keep up with it."

Ernesto Roman

Ernesto RomanMarr Office Equipment's heyday may be long gone but Marr still knows typewriter users all over his local area. He mentions one that is about a 10 minute drive away, in south Providence – a law firm named Tomasso & Tomasso, co-owned by brothers John and Ray, both attorneys. "We sound exactly alike," says John, laughing as he introduces himself over the phone. Do they actually still rely on typewriters? Absolutely. "There's not a day that goes by that we don't use them," says Tomasso. "This is really still the best way."

The firm's office has three typewriters, John says and his colleagues still use them to type up cheques and fill in legal forms to ensure the details on those documents are legible. Plus, there's a security angle. It's very hard to hack a typewriter since they are not connected to the internet. In 2013, jaw-dropping details emerged about the extent of US intelligence agency surveillance programmes. This prompted the Russian Federal Guard Service (FSO) to revert to typewriters in an attempt to evade eavesdropping. German officials were also reported to be considering a similar move in 2014. (During the Cold War, Soviet spies actually developed techniques for snooping on electric typewriter activity, a form of "keylogging" technology – where the keystrokes inputted on a keyboard are captured. US operatives also reconstructed text from typewriter ribbons – meaning that even typewriters aren't completely safe.)

I ask Tomasso whether there are downsides to using the typewriter – isn't it harder to correct mistakes? No, he replies, he has a model with an "eraser ribbon" that seamlessly covers up a mistype. Plus, the typewriters are inexpensive to run. Replacement ink ribbons cost around $5 (£4), he estimates. Replacement printer ink cartridges can cost several times that.

Besides, Tomasso loves to see his writing materialise instantly on the page in front of him. "There's more of a sense of accomplishment than just letters that appear on a screen," he explains. "It's one of those amazing devices that just makes our life better – I think that's the purpose of technology."

Further west, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is a real estate agency called Jarvis Realty, owned and run by Woody Jarvis. "I'm real old school," he says. Jarvis, too, regularly uses a typewriter for office work. He gives the example of putting together an offer of purchase for a client. It'll start on the computer but he'll then print the document out and, should he need to make any modifications, he prefers to use correction fluid and his typewriter rather than re-printing the contract and wasting a lot of paper. "Our contracts are very legible and easy to understand," he says. He'll also occasionally type up a name and address on an envelope for a colleague. "For me, it works because I know how to make it all work."

Typewriters have had a long and colourful history. Centuries ago, tinkerers came up with early, experimental typing machines but they didn't really catch on. Then, in 1868, the first device actually called a typewriter emerged: the Sholes and Glidden Type-Writer, which was patented that year by four inventors in Milwaukee. One of the group, Christopher Latham Sholes, also invented the Qwerty keyboard. Without him, typing – even on computers – might be very different today. By the 20th Century, typewriters were everywhere. Millions of the machines were sold in the first few decades of the 1900s and by the mid-1980s, the typewriter industry was worth more than $1.1bn (£764m) in the US alone, according to press reports from the time.

In the 21st Century, typewriters have remained popular in certain corners of the world, despite the rise of computers. In India, for example, typewriters have found a flourishing market among enthusiasts and are still a common – albeit steadily vanishing – sight in courts and government offices.

Ernesto Roman

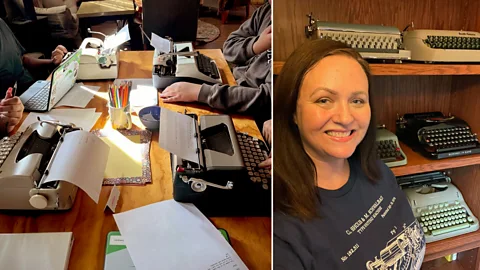

Ernesto RomanJarvis's cousin, Lisa Floading, who works at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design, is a big fan of typewriters. She has 62 of them. "There's something very inviting about a typewriter waiting with paper in it," she explains. "I have them all over my house."

Floading uses a typewriter every day, she says, to make lists or write letters, and for office admin. "There it is, you wrote three pages, boom, done. That's kind of lost on the laptop," she says. And she'll even bring a typewriter to her local coffee shop sometimes so she can work on it there. People regularly come up to her to ask about it, she says.

In June, Floading took part in an event in Milwaukee called Qwertyfest – intended to celebrate both the typewriter and the Qwerty keyboard layout, in memory of Christopher Latham Sholes. Among the attractions was a room full of typewriters where attendees could simply sit down and type. The sound of clacking keys and carriages returning filled the space. It was once a sound common in typing pools in businesses around the country.

Ernesto Roman

Ernesto RomanJim Riegert, now in his 70s, remembers what it used to be like. "Back then, typewriters were pretty big. Typewriters and adding machines," he says, referring to desktop calculators. "It got really difficult in the typewriter business about 25 years ago," he says. "The internet was coming on and killing us, too." He runs Typewriters.com and, despite a decline in sales in recent decades, he still shifts four or five electric IBM typewriters every week. "I just sold 12 to a prison that's putting them in the library because they don't let prisoners use computers," he says. Funeral homes, some of which use typewriters to compile death certificates, are also regular clients.

Riegert's business is based in the city of Tucker, Georgia. His own office, inside a giant warehouse, is crammed witharound 70 or 80 IBM electric typewriters – second-hand units, which he services and sells. The build quality is top notch, he stresses. A prime model could set you back $749 (£594). When they were brand new in 1984 they would sell for around $1,000, but even accounting for inflation they have retained a surprising amount of value in the digital age. "They're still the best typewriters you can buy," he says. These days, demand might be low – but somehow business remains steady, and profitable.

IBM, nowadays arguably better known for supercomputers such as Watson, sold its typewriter business to Lexmark in the early 1990s. However, an IBM spokesperson says on very rare occasions, "some people do ask for old manuals or service documents for typewriters, which we can provide if they're in the archives". Lexmark, meanwhile, sold its last typewriter in 2002 and no longer has any typewriter-related services, though some of its former distributors still carry out maintenance on IBM Lexmark typewriters.

Ernesto Roman

Ernesto RomanIf, on the other hand, you want to buy a brand-new typewriter, that too remains possible. Many thousands are still manufactured every year. Todd Althoff is president of Royal, a US company that has been making typewriters since 1904. "We're going to continue," he insists. "Obviously [there is] not that much growth but it's sustainable and we keep the factory busy."

The factory is in Indonesia, he explains, and is run by a team from Nakajima, a typewriter manufacturing firm from Japan. Every year, Royal still sells around 20,000 new electric typewriters and more than double that amount of mechanical typewriters. The latter have become desirable partly as decoration – a librarian might buy one for a display at the front of their library, for instance, suggests Althoff. The mechanical and electric models Royal sells cost between $300 (£238) and $400 (£317).

Thankfully, there are still companies that make new typewriter ribbons, notes Paul Lundy, who runs Bremerton Office Machine Company, a typewriter repair business in Bremerton, Washington. "Those accessories are readily available," he says. "As a person who repairs typewriters, that's always running at the back of my mind – why are businesses still using these things?"

But he has some good examples, including workers in warehouses who must continually process the transfer of goods by filling out forms. It's hard to feed these complex forms into a computer printer so that information gets printed onto them in exactly the right places. So, says Lundy, the warehouse workers prefer to insert the form into a typewriter and type it up by sight instead.

Grant Hindsley

Grant HindsleyOver the years, he's noticed that some aging typewriter parts are becoming more fragile, in some cases possibly as a result of plastic fatigue. But overall, they remain "incredibly durable" machines, he says.

And, best of all, when you sit down to use one, there are no distractions. You just type. One of Lundy's customers who appreciates this perhaps more than most is Anjali Banerjee, a novelist who lives in Seattle. She has published 15 books and she wrote the first drafts of the last three on a typewriter.

Some years ago, Banerjee began getting increasingly frustrated when trying to type new material on her computer. Notifications kept popping up or her word processing software would repeatedly intervene on things like spelling and grammar. So she went out and bought a typewriter.

Banerjee started with an electric model but then got interested in mechanical versions. Now, she claims that her first drafts emerge more fluidly when she sits down at a typewriter rather than a screen. "I have to keep moving forward. The story moves faster, if that makes sense," she says. "You have to put it out there, like clay." The further editing – or shaping of the clay – takes place after she scans the typewriter-produced drafts into her computer.

Banerjee goes on to admit candidly: "I developed what we call 'typewriter fever'."

Grant Hindsley

Grant HindsleyFollowing her first typewriter purchase in 2019, she built up an astonishing collection of no fewer than 120 machines. However, she has recently slimmed this down to about 80 typewriters and plans to sell off roughly half of those. In essence, it became an epic search to find her perfect typewriter. And Banerjee has definitely discovered some personal favourites, such as her Olivetti Studio 45, an Italian-made model. The author, who also plays piano, compares typing on a typewriter to playing a tune on the instrument. It's percussive. And it requires more effort from your hands and fingers than a computer keyboard. She has sought out typewriters that are just right – not too stiff, not too loose. But a good, deep "throw" (the depth of key press required) is satisfying, she adds.

Typewriters engage the senses, says Banerjee. You hear the energetic clack-clack-clack of the keys as you work away. You might even detect the musty aroma of old offices or maybe long-faded cigarettes. In that atmosphere of industry distilled, you focus in on what you're doing. "I lose time," she says. She'll look up and two hours may have gone by. Her thoughts are right there on the pages in front of her.

Lisa Floading

Lisa FloadingAs long as there are writers like Banerjee, and office workers who prize well-practised convenience over modernity, typewriters will never be completely obsolete, it seems.

That ought to keep Mike Marr busy, at his shop in Rhode Island. "I was born and bred to repair typewriters and office equipment," he says. "It's all I know in life."

Many of the ailing machines that customers bring to him are fundamentally in good condition, merely requiring a clean and a re-oiling of their moving parts. A smattering of decades-old grease in the machine's tightest nooks and crannies has simply dried up. But that's an easy fix. The typewriter itself is perfectly fine – and it has plenty more work to do.

--

For more technology news and insights, sign up to our Tech Decoded newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights to your inbox twice a week.