Colossal squid: The eerie ambassador from the abyss

Emannuel Lafont/ BBC

Emannuel Lafont/ BBCThe world's largest invertebrate remained hidden from humanity until a tantalising glimpse 100 years ago. It would take decades, however, before we finally came face to face with the colossal squid.

Under sombre, mausoleum lighting at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa rests a monster. Its enormous body lies in a huge glass coffin, thick tentacles trailing beneath a strange, mottled body that once contained two huge staring eyes.

Amongst displays of animals that inhabit the seas around New Zealand, it resembles a creature from another world – reminiscent of the first awestruck description of a Martian by the nameless narrator in H G Wells' The War of the Worlds. The bunches of tentacles beneath a bearlike bulk and a nightmarish beak of a mouth.

But this is no interplanetary visitor, rather something from the inky blackness of our own inner space: a colossal squid. It is the biggest invertebrate on Earth and the rare specimen on display at Te Papa, the shortened Māori name by which the museum is better known, is the first of these mysterious creatures to have been recovered alive – just briefly – in human history.

--

For an animal of such enormous size, the colossal squid has an extraordinary ability to keep itself hidden from human eyes. Its discovery was a gradual process, with hints of its existence stretched out over decades. Then – almost exactly 100 years ago – we got our first glimpse of these almost mythical creatures.

Te Papa/ CC BY 4.0

Te Papa/ CC BY 4.0Until April 2025, no colossal squid had ever been positively identified as being observed in its natural habitat, though there have been some unconfirmed sightings. In June 2024, scientists from an Antarctic expedition said they may have filmed one on a camera attached to a polar tourism vessel in 2023, but scientisist were still analysing the footage when a confirmed sighting was announced.

Because the animal lives so deep in an ocean only recently visited by modern humanity, the first clues to its existence were the occasional remains found in the bellies of whales that hunt them. Semi-digested fragments hinted at some huge, strange squid whose arms ended in clubs with sharp, gripping hooks and evoked scenes of titanic battles for survival in the ocean depths as they tussled with whales.

Unknown giants of the deep

The colossal squid's elusiveness underlines just how little we know about the deep oceans. And there could be other large sea creatures waiting to be discovered in some of the least explored depths.

There are thought to be up to two million species living in the oceans, with some estimates putting the figure higher. So far, we know about fewer than 250,000, according to the World Register of Marine Species.

Then, in 1981, a Soviet trawler called Eureka caught an enormous squid in its net while fishing in the Ross Sea off Antarctica. The discovery went largely unnoticed until the end of the Cold War a decade later. In the year 2000, Soviet scientist Alexander Remeslo wrote about the incident on The Octopus News Magazine Online forum, giving first-hand testimony on how the animal was captured.

"It was early morning the 3rd of February, 1981, when I was working in Lazarev Sea near Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica," he wrote. "A fellow scientist rushed into my cabin and pushed me in the ribs, shouting: 'Wake up, we caught a giant squid!' With my cameras slung around my neck I ran on deck. There lay a huge reddish-brown squid. None of the crew members, several of them sea dogs who had been wandering all over the seven seas, had previously seen something like this."

Remeslo's account paints an evocative picture: fine snow was falling on the deck of the ship, and the light was so poor that he struggled to take a properly exposed image of the squid, which had been removed from the net and lay lifeless in front of him.

"Burning with impatience to see the results of my photography, I decided to develop the films immediately on board of the vessel, rather than keeping them for developing in a professional laboratory at home," writes Remeslo, now a scientist at the Atlantic Research Institute of Marine Fisheries and Oceanography in Kaliningrad, Russia, in his account. "The quality of the photos taken that day leaves much to be desired. But the most important thing has been done anyway – to document what was most probably the world's first big specimen of the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni), which was raised from the depths onto the deck of a vessel and not removed from a sperm whale's stomach!"

A black-and-white image taken by Remeslo and shared alongside his story shows a pair of the Soviet ship's crew crouching next to the dead squid. The creature's two long arms can be seen in the foreground, clenched like fists. According to Remeslo, the squid measured 5.1m (16.7ft), with the mantle alone measuring more than 2m (6.6ft). The squid was described as being a juvenile female, and not yet fully grown.

It would be more than 20 years before another immature colossal squid would be found. This time, in 2003 it attracted worldwide attention. "Super squid surfaces in the Antarctic", wrote BBC News at the time. The squid was found floating dead on the surface in the Ross Sea off Antarctica and was hauled aboard a fishing vessel.

The animal's remains were transported to Wellington, New Zealand's capital, where two scientists – Steve O'Shea and Kat Bolstad of the Auckland University of Technology – reassembled the creature and examined it. It helped turn O'Shea into an internationally recognised authority on giant squids.

Te Papa/ CC BY 4.0

Te Papa/ CC BY 4.0"We're sitting there at Te Papa and I've got this bloody enormous thing sitting on a slab," says O'Shea, who now lives in Paris. "It's completely defrosted. I called up a couple of contacts, and I said, 'Look, I've got this colossal squid sitting on a slab here at the department. You want to come and have a look at it?’."

O'Shea was so excited that he hadn't noticed the date: 1 April 2003. Everyone mistook it for an elaborate practical joke. "Nobody took me seriously," he says. "And it wasn't until we sent them a photograph of what we were dealing with on the slab did the press converge on us… my phone didn't stop ringing for a month."

Even for someone like O'Shea, familiar with large cephalopods, the colossal squid was still a dramatic sight. "I'd never seen anything like it before," he says. "I had worked a lot with a fellow called Malcolm Clarke on a number of my documentaries in the past, and he had spent a lifetime studying the stomach contents of sperm whales – and had reported many times their beaks in the stomachs of sperm whales. I was aware of the colossal squid's existence. I couldn't have imagined it looked anything like what we had in front of us."

O'Shea had previously been studying another large squid species – the giant squid, Architeuthis dux, which can reach up to 13m (43ft). What he was faced with in 2003 was a different beast entirely.

"The giant squid, to an extent, I was bored with, because it was just a large, very dull squid," he says. "It's got no real charismatic feature other than its size. And here I am dealing with something that's got these swivelling hooks on the arms and a beak… considerably larger and considerably more robust."

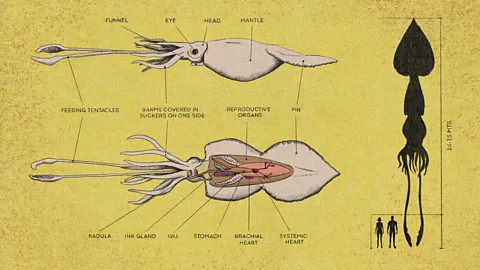

Colossal squid are thought to grow to more than half-a-tonne (500kg) in weight. While the giant squid's trailing tentacles are far longer than the colossal squid's, the colossal's mantle is both larger and heavier.

Finally filmed

A colossal squid was finally filmed in its natural environment for the first time in March 2025, 100 years since the species was first identified. Scientists captured footage of a baby colossal squid during a 35-day voyage to study species near the South Sandwich Islands in the south Atlantic Ocean.

But the colossal squid is far more than a squid transformed to larger-than-usual size. Its eyes – which can measure 11in (27.5cm) across – are the largest eyes to be found in any animal yet discovered. The beak, made from a protein similar to that found in human hair and fingernails, is a sharp, clawed mouth that cuts off slices of prey. Another organ called the radula, studded with sharp teeth, shreds the chunks into smaller pieces.

On its arms, the squid has prominent hooks. Other squid, including the giant, have teeth within the suction cups. The colossal squid's are far more prominent – curved hooks the squid uses to latch onto its prey. Incredibly, the hooks found on its tentacle suction cups can rotate 360 degrees. Scientists still don't know if the squid can swivel these hooks at will, or whether they move of their own volition when the hook latches onto prey.

Te Papa/ CC BY 4.0

Te Papa/ CC BY 4.0O'Shea used the discovery of the squid and the ensuing media coverage as a platform to attack New Zealand's fishing industry and what he called some of its destructive practices in the Southern Ocean. He says this led to some resistance to his involvement when an even bigger squid (the one on display in Te Papa) was recovered a few years later. Amid the furore, however, O'Shea managed to finally give Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni a common name:colossal squid.

Two years after O'Shea stretched a colossal squid on his slab, fisherman nearly landed a live specimen. In 2005, a ship hunting Patagonian toothfish near South Georgia in the South Atlantic caught a colossal squid on one of their lines. Five of the fishermen toiled unsuccessfully to bring the squid aboard. A recording of it thrashing on the surface is believed to be the first footage of a living colossal squid ever captured.

Recommended by the editor

While editing this article, I was reminded of another article that we published in 2023 about how deep sea creatures can survive the crushing depths they inhabit. They boast a range of anatomical and cellular adaptations that help them to resist the intense pressure the water exerts on their bodies. You can find out more in this article by Isabelle Gerretsen.

The author of this piece, my colleague Stephen Dowling, has also previously dug into some of the new species of deep sea shark that have recently been discovered.

Richard Gray

In February 2007, a New Zealand fishing vessel called the San Aspiring, also hunting for Patagonian toothfish in the Ross Sea near Antarctica, pulled up its lines. Tangled amongst them was a colossal squid, fully grown and still alive.

The squid's decision to try and grab a quick meal proved its undoing. "It decided to scavenge a toothfish off the long line and got itself wrapped up in the backbone and trace [part of the fishing line] and was pulled to the surface," says Andrew Stewart, Te Papa's curator of fishes and one of the world's most respected fish scientists. The animal was estimated to weigh up to 450kg (990lb) and measured some 10m (30ft) in length. Some of the boat's fishing equipment had gouged deep cuts into its body, and the squid was badly injured and likely to die if returned to the ocean.

Vessels like the San Aspiring carry New Zealand fisheries scientists on their expeditions, partly in case they come across new or rare species. "They looked at this thing right at the surface, right up against the edge of the boat, and they realised that because the damage it had incurred from the backbone on the trace that, no, this wasn't going to be able to make it away under its own steam," says Stewart. "It was brought on board with great difficulty, because you're dealing with this very floppy specimen. How do you get it up out of the side of a ship and onto the deck, and then, what do you do with it then?"

A colossal squid of this size, relatively intact and still alive when it reached the surface, certainly met the scientist's benchmark for something worth preserving. But then they had the challenge of how to keep it cold and intact while they finished their fishing mission.

"They managed to get it below deck, and they froze it in what's called a pelican bin," says Stewart, who took the initial call from the fisheries observer programme to say a colossal squid had been caught. "These are one-cubic-metre bins (35 cubic ft) that contain fuel oil and things like that. And when they get to the Southern Ocean boundary, these are brought below decks. They're emptied and cleaned, the top is cut off. They're used for putting in offal and scientific specimens. So they just put this half-tonne thing in this cubic-metre bin, and froze it as a giant, colossal squid popsicle."

When the San Aspiring eventually made its way back to Wellington, that made it relatively easy to offload, says Stewart. "All you have to do is run a forklift for a pallet jack and move it," he says. On arrival it was transported straight to Te Papa's walk-in freezing facility.

"We were scratching our heads, going, 'How the hell are we going to handle this thing?'," says Stewart.

Even thawing a frozen specimen this large was an issue, let along trying to preserve it. "The way these things are constructed, and the chemistry of them, it could well rot on the outside with the inside still frozen solid," Stewart explains. "So a giant wooden tank was built and lined with three layers of rubber cement, and then three layers of heavy-duty polythene plastic.

"Stephen [O'Shea'] and co came up with the idea [that] if we make a very chilled brine solution, that means it will slow down the rate of thawing." This gave the scientists much more control over the thawing process.

Te Papa/ CC BY 4.0

Te Papa/ CC BY 4.0"If you freeze something, ice expands and breaks down the connective tissue and will certainly make something more gelatinous," O'Shea adds. "When we defrosted that thing, of course, the ice crystals expand, and everything blows up. Then when the ice melts, everything shrinks. As it lay on the slab, defrosting, we could see it losing bulk."

In order to preserve the body, its tissue had to be injected with a formalin solution, but getting the right mix was crucial, says O'Shea. "That was a 4% formalin solution from memory. Once I fixed it from the inside out, we then immersed it into a vat of formaldehyde/seawater solution. And then we had to monitor that thing over the course of the next 48 to 72, hours, monitoring the pH, because the minute the pH goes anything above seven, the calcareous hooks that align in the arms and the suckers start to dissolve."

When the pH of the solution got too acidic, the tank was emptied and then another formalin solution was added. "It preserved the colour," says O'Shea. "It was a beautiful looking specimen."

Te Papa knew the squid could become a star attraction. But the giant defrosted body created an entirely new problem, says Stewart. "One, how do we display it? And two, how do we transport this big floppy thing?"

The colossal squid is adapted to living in the crushing pressure of the deep ocean, meaning its soft body is supported by the surrounding water. In the open air, it collapses.

"If you're not careful, the whole thing could detach," says Stewart.

Te Papa's solution was to contact a glass fabricating company in the nearby city of Palmerston North, which produced a special curved case for the squid using a technique that didn't produce bubbles during its construction.

The case was assembled right next to where the thawed squid was being kept in central Wellington, some 900m (984yds) from the museum itself. The museum's experts then had to work out how it could be both preserved and transported. "What do we preserve it in, display it in, and how do we get it from here down the road?" Stewart says. "We can't display it in alcohol or formalin because of the issues around health and safety and fire risk management and all that kind of stuff." A suggestion by another member of the team was to submerge the squid in polypropylene glycol. While Stewart says this is non-toxic, "they have to add a rather toxic biocide to it in order to stop any bacterial action, fungal action".

While the team were working out how to move their colossal cadaver, something elemental came to their rescue: gravity. Wellington is a hilly city, and the squid was at the top of an incline. They came up with a plan: the squid would be transported to the museum late at night on the back of a flatbed truck in the container, but with all the liquid removed in order to save weight. "It just sort of glided down late at night when there's no traffic, and the traffic lights could be set [to let it through.]" The squid was then safely unloaded and took up residence in Te Papa, an ambassador from an abyssal zone few humans will ever visit.

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/ BBC"Some people have said, 'Oh, it looks bit rough and falling to bits, but it's no worse than once it came out of formalin," says Stewart. "This poor thing had been sort of fairly badly damaged already by the time they got it up to the side of the boat.

"There will be gradual and slow decay of it, you can't stop that. Light will affect it, temperature fluctuations… it will degrade. It does look a bit like Frankenstein's monster, with stitching holding things together," says Stewart. "Peter Jackson [the film director] has taken a few notes."

--

Specimens like the one at Te Papa offer vital clues about the biology and behaviour of this mysterious deep sea mollusc. The colossal squids that have been brought up to the surface to date have nearly always come from deep water. They have either been ensnared in cables or attacked fish caught on fishing lines, attracted by the prospect of an easy meal. Their interactions with humanity have been inadvertent, often violent and dramatically short.

Scientists have been able to slowly piece together fragments of the colossal squid's life cycle and habits. Much, however, remains mysterious. It is like trying to create a coherent story of a person's life through a handful of holiday snapshots – the majority lies beyond the frames.

Colossal squid are highly evolved for a cold and dark environment, and live near the top of the food chain in the bitterly cold waters they call home. They prey on large sub-Antarctic fish such as Patagonian toothfish (also known as Chilean sea bass) – dozens of these fish caught by trawlers between 2011 and 2014 showed wounds characteristic of the squid's hook-covered tentacles, according to Vladimir Laptikhovskiy of the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science in the UK. "Taking into account the size of adult squid, the toothfish probably is its most common prey species, because no other deep-sea fish of similar size are available around the Antarctic," he told New Scientist in 2015. There are some reports, however, of young colossal squid – which live closer to the surface – being found in the diets of penguins and other seabirds.

Few animals are thought to prey upon colossal squid apart from sperm whales and southern sleeper sharks, slow moving but powerful deepwater sharks that can grow up to 4.2m (14ft) long. The colossal squid's size is a form of protective adaptation – the bigger you grow, the less likely you are to be eaten by something else.

And this growth happens quickly. Much like giant squid, colossal squid are not thought to live much longer than five years, although their exact lifespan – like so much about these creatures – is largely a mystery. They appear to live longer than smaller species of squid – most of which live little more than a year – but remarkably short given their great size. This type of growth is known as abyssal gigantism – it's seen across many other species which inhabit cold, deep waters, including spider crabs.

This gigantism, strangely, doesn't require enormous amounts of energy. A study in 2010 from the University of South Florida estimated that a colossal squid could survive for around 160 days on a single 5kg (11lb) toothfish – the equivalent of only 30g (1oz) of food a day, or just 45 calories. The temperature in the deep Southern Ocean where they are found typically hovers around 1.5C (34.7F), and studies suggest the larger animals become in these conditions, the more efficient their metabolism becomes. Research on the metabolic rate of colossal squid suggests they have a slow pace of life, spending much of their time passively floating, waiting to ambush their prey.

The enormous eyes of the colossal squid are thought to have evolved to detect large predators such as sperm whales rather than spot prey at long distances.

Small juveniles are thought to live closer to the surface – above 500m (1,640ft), but as they grow they descend to depths of up to 2,000m (6,560ft).

Isabel Joy Te Aho-White/ Te Papa

Isabel Joy Te Aho-White/ Te PapaMuch of the squid's life cycle remains hidden from view. One of Te Papa's staff has attempted to fill in the gaps in the squid's life, and written a book about it. Whiti: Colossal Squid From the Deep, a children's book written by Victoria Cleal and released in 2020, tells the story of a colossal squid's life from hatching out of a minuscule egg to becoming the world's largest invertebrate (it was illustrated by Isobel Joy Te Aho-White)

Cleal said she was chosen to write the book because of her experience writing labels for exhibits aimed at children, making them as friendly and informal as possible. "They knew there's basically an insatiable desire amongst children for information about the colossal squid, whether it's in a book or an exhibition label or in a video," she says. "It constantly fascinates visitors. Everyone who comes to the museum wants to see the colossal squid.

"There are now kids who saw it at the beginning who come back as young adults… and I just love the thought that one day they might bring their children back to see it."

Despite the painstaking effort that went into displaying the squid, the years have still taken their toll. "That squid is not looking at its best anymore," Cleal says. "The eyes have been removed and other body parts, there's a lot of stitches. I did want to mention that squid in the book, just to give some connection between the book and Te Papa. But that squid came to a very unhappy ending because it got itself hooked on a line and died."

Telling the story of a different squid – one still roaming the cold watery world off the coast of Antarctica – allowed Cleal to imagine a whole life cycle, even if so much of it is still unknown.

With the help of squid experts like Kat Bolstad, Cleal set to work. Bringing a male squid into the story wasn't possible, because one has never been observed. "But there are things we can imagine, like what it would be like to be 2,000m (6,561ft) down, even though nobody's been down there, in the Ross Sea." She says it was all about keeping Whiti (a Māori word meaning to change or turnover) within the realms of possibility.

Cleal says the squid's enormous size and frightening appearance is part of its allure with a younger audience, but that ultimately this undersea "monster" is relatively harmless. Many descriptions of the colossal squid evoke legends of the mythical kraken terrorising sailors of old, but in reality the creatures live so deep and so far from shore that a human is unlikely to ever find themselves face-to-face with one in the water. But the fact we know so little about the colossal squid and the realm it inhabits only makes them more intriguing, says Cleal. "It's such a mysterious world, I think that captures everybody's imagination. We don't know what's going on down there."

Cleal said she was partly inspired to tell the story of the colossal squid to make children imagine what else might live in the cold, inky depths the squid calls home. "I just think that's great for kids, to be an advocate for science as a career, to think that that there are things to discover. It hasn't all been found yet? And why don't you try to become a marine biologist too?"

--

James Erik Hamilton was a marine biologist, a naturalist and oceanographer who spent much of his life in the Falklands and surrounding islands. He arrived in 1919 to conduct a survey of the fur seal population. He became the Falkland Islands Dependencies administrator a few years later, and spent much of the 1920s working on whaling ships or on the stations that supported them across the South Atlantic islands.

Hamilton would investigate the contents of the whales' stomach as part of his job, and in the winter of 1924/25, found something in the stomach of one sperm whale which he had never seen before: tentacles from some large, mysterious squid that ended in sharp gripping claws.

Javier Hirschfeld/ BBC

Javier Hirschfeld/ BBCHamilton believed they were new to science. He had them preserved and then sent them to the Zoological Department of the British Museum back in London.

A report in the Journal of Natural History soon after reported the creature's arms "furnished with a group of four to nine large hooks" and its hand consisting of "hooks alone, which are capable of rotating in any direction". Hamilton's specimens were the first remains of a colossal squid to be scientifically recorded. The species, described for the first time in 1925 by Guy Coburn Robson, would be named after him. Hamilton died in 1957, decades before a complete colossal squid would be discovered.

While talking to O'Shea, I mention the tentacles Hamilton discovered a century ago. His response is immediate: "Have you seen them yet?" It turns out those first, species-defining tentacles still sit, suspended in a jar, on the shelves of the Molluscs Department at the Natural History Museum in London. An email to O'Shea's friend, Jon Ablett, a senior curator at the molluscs department at the museum, elicits an invitation to see them a few days later.

A couple of weeks later, steers me through the museum's seemingly unending corridors. It is the proverbial needle in the haystack. "Just the molluscs department alone, we have eight million objects," Ablett says cheerily.

In these archival storage units sit dozens upon dozens of jars, each of them containing an animal – or parts of an animal – once new to science. Ablett finds the right door and opens it. There, in a jar with the words "Mesonychoteuthis Hamilton, 1925" lie the remains of the squid that had so intrigued Hamilton a century before. The first scientific evidence of the giant lurking far below the waves.

Javier Hirschfeld/ BBC

Javier Hirschfeld/ BBC"Strangely, we don't really know that much about how the specimens were found and recovered," Ablett says. "The way that specimens were collected at the time, it almost wasn't thought of as important. And of course, you also don't know what's important until you realise it's important."

The whale was thought to have been taken off the Falkland Islands, and the tentacles sent off to what was then the British Museum. Robson examined them when they arrived.

"The way we preserve animals hasn't really changed over the last 200 years," Ablett says, noting that alcohol is still sometimes used. "With lots of invertebrate animals, especially deep-sea creatures, the preservation techniques can really distort the features and generally shrink them." The tentacles, now a century old, look lumpen and weirdly coloured, but the swivelling claws that so intrigued Hamilton are still there.

"They are, you know, half-chewed stomach remains… basically the ring of flesh around the mouth, most of bits of the arms, and that's pretty much it," Ablett says. "But he [Hamilton] was able to recognise that they were so distinct from any other known squid that they had to be a new species. And I guess sperm whales are really good at catching things in the deep ocean, much better than we were at the time, and probably even now."

The colossal squid's remains predate molecular classification, and further study of this by-now century-old squid may yield further clues about its life. One of the things scientists do know, Ablett says, is that the colossal squid and the giant squid are entirely different animals. "They're not very closely related," he says.

The giant squid, Ablett says, throws up some intriguing questions about why some squid grow so large, when others remain relatively small. "The thing that always fascinates me is lots of the species related to the giant squid – these are the Cranchiid squids, or glass squids – are very, very small, you know, a couple of inches long. But just this one species is so large."

A century on from the colossal squid's initial discovery, Ablett says, we still know so little about them. In his 20 years of studying this elusive abyssal giant, "they're just not turning up in enough numbers", he says. "They haven't been observed in the wild, in their natural state yet."

Ablett says there are hints in the biology as to how the squid may live their days in the deep, cold waters of the Southern Ocean. "You look at the colossal squid, it's very blobby. It doesn't look particularly sleek." This for him perhaps underlines its status as an ambush predator. "Is it hiding in these dark oceans, waiting for things to pass?" he asks.

Ablett says one thing scientists have found is that where you find colossal squid, you won’t find giant squid. The respective big beasts of the cephalopod world appear to have drawn some invisible line in the world's oceans, which neither crosses. And very cold oceans are something of a hotspot for very large organisms, he says. "It just seems to be a kind of trend with especially polar organisms, that they get very, very big. I mean, one benefit of getting massive is, of course, nothing can eat you."

More like this:

• The unknown giants of the deep oceans

The century-old tentacles preserved in the museum's jar are not the only colossal squid remains the museum has to hand. In the basement, hidden from public view, is a room filled with jars and tanks containing a bewildering array of creatures (you'll have seen it if you've watched the Tom Cruise version of The Mummy). An entire Komodo dragon, a deceased former resident of the London Zoo, floats in a large tank. The heads of deep-sea sharks leer toothily from the interior of huge jars.

Other jars contain bigger remnants of recovered colossal squid. Ablett even frees some of these from the tanks for photographs, the preserved flesh glinting under the strip lights as he holds them in front of the camera.

Javier Hirschfeld/ BBC

Javier Hirschfeld/ BBCIn another tank – a really, really big tank – the partial remains of another colossal squid are suspended in preserving solution. Much of the rest of the tank is taken up by an entire giant squid, its long, tentacles trailing far beyond the mottled mantle. You could imagine a very long line of visitors filing past it, but this room is out of bounds to the general public. The tank had to be made by specialists usually involved in art installations. If the museum ever finds itself lucky enough to take delivery of a complete colossal squid, they might have to build another. In death, at least, the two squid might actually meet.

In the meantime, scientists will continue to piece together what they can about the world's largest invertebrate. But it also raises questions about what else might be hiding in the depths, still waiting to be discovered.

"Most species discovery tend to be small, because these are the things we miss," says Ablett. "But I'd be lying if I said I don't harbour hope that there is something even bigger than a colossal squid. I mean, what are we going to call it?"

--

I

f you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram

.