Greenland is getting a lot of international attention for its mineral resources – but what is hiding under the ice?

Nigel Baker and GEUS

Nigel Baker and GEUSThe riches thought to lie beneath Greenland's icy terrain have been coveted for more than a century. But how easy are they to access, and will climate change make any difference?

The allure of Earth's biggest island is undeniable. Over the past millennia, Greenland has captivated visitors, bringing everyone from Erik the Red, who founded the first European settlement over a thousand years ago, to the Allied Forces of World War Two to its isolated shores.

And, like the ever-warming climate, interest in Greenland is (again) heating up as the island has attracted the attention of US President Donald Trump.

Detailed mapping collaborations and explorations carried out over more than a century have uncovered evidence of important mineral resources in Greenland – including rare earth elements and critical minerals used for green energy technologies, as well as suspected fossil fuel reserves.

But – despite the unbridled excitement brewing around Greenland's treasure trove – the process of finding, extracting, and transporting minerals and fossil fuels is a multilayered, multinational, and multidecadal challenge.

The US' long interest in mining Greenland

Greenland is huge – it's the world's largest island – and has considerable untapped mineral wealth. Now, US President Donald Trump has shown renewed interest in taking control of the territory. But it's the not the first time the US has tried to acquire the island, an autonomous Danish dependent territory.

• 1867: Then US Secretary of State William Seward raised the idea of annexing Greenland, along with Iceland.

•1910: The then US ambassador to Denmark, Maurice Francis Egans, made the Danish government an offer: to exchange Greenland in return for the Dutch Antilles and the Philippine island of Mindanao.

• 1946: Then US Secretary of State James Byrnes presented the first offer to buy the island for $100m in gold bullion – worth roughly $1.5bn (£1.3bn) today.

• 2019: Trump first showed interest in the purchase of Greenland – which was quickly rejected by Danish PM Mette Frederiksen who described the suggestion as "absurd".

On most maps, Greenland looks enormous, rivalling the size of Africa. Blame this exaggeration on the popular Mercator map projection, which stretches and enlarges countries near the poles, exaggerating their size. In reality, Greenland is around 2m sq km (770,000 square miles) – roughly the size of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Everywhere on Earth, the scars and signatures of immense stretches of time are recorded in geology. Spewing volcanic eruptions and slow-cooling magmas, giant continental collisions and taffy-like rips that eventually open up new oceans – all these geologic performances are written in the rocks. And an old land mass like Greenland contains detailed documentation of the Earth's history.

"The history of Greenland goes back as far as the history of pretty much anything in the world," explains Kathryn Goodenough, principal geologist with the British Geological Survey. She explains that Greenland, once upon a time, was part of a larger continent that would have included some of northern Europe and some of North America today. Around 500 million years ago, Greenland was part of a supercontinent, wedged between Europe and North America.

But the Earth is always evolving. Around 60 to 65 million years ago, the supercontinent began to pull apart, creating a rift that eventually opened, creating the North Atlantic Ocean.

Greenland split from Europe, drifted westward, and even travelled over the Icelandic hotspot – a place where molten lava from deep beneath the Earth's crust wells up, contributing to the volcanic activity which formed the island of Iceland. Today, Greenland hosts everything from Precambrian basement rocks to yesterday's glacial sediments – all of which could hold an array of valuable resources.

Beyond mineral resources, scientists estimate that Greenland has enormous reserves of oil and natural gas. Since the 1970s, oil and gas companies have tried to find ancient reservoirs off the coast of Greenland, but their attempts turned up empty. Still, Greenland's continental shelf geology does show similarities to other fossil fuel sites in the Arctic.

Alamy

AlamyGreenland resembles a Cadbury Creme Egg, with an outer, hard margin enclosing an interior of white ooze. Most of the island is covered by the slow-flowing Greenland Ice Sheet that drains towards the coastline through a number of outlet glaciers. Only around 20% of the island is ice-free, consisting of craggy mountains, fjord-cut cliffs, and an occasional town with technicolour homes.

"The exploration of Greenland, especially north-east Greenland, was a hot topic 120, 130 years ago," says Thomas Find Kokfelt, senior researcher at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS). Various minerals were discovered and mines began to pop up.

In 1850, the mineral cryolite, the "ice that never melts", due to its extremely high melting point, was found in south-west Greenland. Settlers started mining cryolite after they learned its use in making bicarbonate of soda. During World War Two, the Ivittuut mine supplied the Allied forces with cryolite – an important mineral in the production of aluminium used in planes.

Geologic mapping in Greenland began in earnest after World War Two. After 20 years of trekking along the coastline, it became clear that mapping was a humungous undertaking. "If you divide all of the ice-free areas of Greenland, you can probably fit 200 map sheets of a one to 100,000 scale," Find Kokfelt says. When the geologists did the maths, they realised it would take 200 years to finish mapping at their current rate. They pivoted to a coarser resolution effort and finished the initial geologic maps of Greenland in the early 2000s.

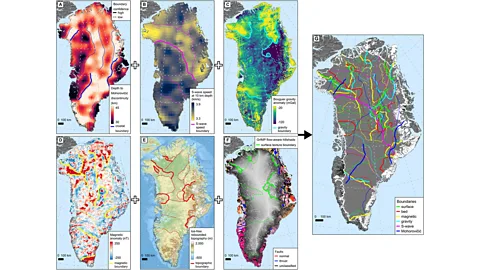

GEUS

GEUSSince then, the GEUS has been refining the maps, zooming in to a finer resolution. To date, geologists have completed 55 maps at a more detailed scale. They have also delved into under-ice mapping efforts. Recently, Find Kokfelt teamed up with geophysicists to create a map of geologic provinces, large-scale regions with distinctive characteristics, beneath the ice sheet. These provinces also hint at what minerals might be present. But like the initial geologic maps, Find Kokfelt is quick to mention the province maps be further refined with more data.

Critical minerals are the materials that keep the world's economy humming yet are getting harder to find. They are especially important for the clean energy transition – experts estimate that demand for mineral and metal resources could quadruple by 2040 in order to meet the demand for energy technologies. Everything from batteries for electric vehicles to windmills and solar panels requires critical minerals.

While many of these minerals are being mined in places like China and Africa, there are several reasons to consider new mining locations, including geopolitics, transportation and access, and economics. Anne Merrild, head of sustainability and planning at Aalborg University, Denmark, points out that as mines in other regions start to dry up, "the deposits in the Arctic become more interesting".

While critical minerals are likely in Greenland, it is unclear if mining is economically viable. That's where exploration comes in. "Mineral exploration is amongst the most challenging and risky of enterprises related to mining," says Simon Jowitt, director of the Ralph J. Roberts Center for Research and Economic Geology at the University of Nevada, Reno. He notes that for every 100 mineral exploration projects, one of them might turn into a mine.

Alamy

AlamyIf the exploration efforts reveal a mine's potential, on average, it can still take about 10 years to go from discovery to production, Jowitt says. "It all depends on where you are, what the infrastructure is, what permitting and other things you have to do to make sure that you're going to be mining in a conscientious way."

Greenland has a notable lack of infrastructure – once out of the cities, there are no roads or railroads through the countryside. "Getting around isn't easy-- you can't drive a four-by-four over the terrain in Greenland,” says Jowitt. Travel is done by boat or air, not car. The lack of established infrastructure, notes Jowitt, could prove a challenge for mining operations.

Processing minerals can also be a fraught endeavour. Unlike a mineral such as gold, which is found in its native state within a rock, rare earth elements are locked within another complicated mineral, explains Goodenough. "Those deposits are very, very difficult to process, and sometimes intimately connected with uranium or with other elements that you might not want to be mining."

Indeed, if a mineral is locked in tandem with radioactive minerals, the mine could stop before a single gram is processed. In 2021, Greenland passed a law limiting the amount of uranium in mined resources, and action which froze the development of a rare earth element mine in Southern Greenland.

The current parliament reflects Greenlanders' concerns over mining's long-lasting impacts. Three legacy mines on Greenland caused marked environmental damage, especially to the water around the island. Merrild explains that in mining, trash rock from the process is put into two categories: waste rock and tailings. "The tailings are the most polluted leftovers, whereas waste rock is considered less damaging," she says. Because of this view, waste rock was dumped along rivers and coastlines.

But the waste rock was not inert.

Alamy

Alamy"The level of heavy metals has been very high in some of the waste rock," Merrild says. Scientists found elevated levels of the metals in everything from spiders to lichen, fish and bivalves near the mines.

The cold temperatures and low salinity around Greenland made environmental recovery painfully slow, and effects can still be detected 50 years later, says Merrild. "Damaging the water is really damaging the whole food supply of Greenlanders and their opportunity to have a livelihood based on fisheries and hunting."

Climate change is drastically affecting the Arctic, with temperatures rising nearly four times faster than the rest of the planet. New estimates show the Greenland ice sheet is losing 30 million tonnes of ice an hour. While the retreat of the inland ice will reveal more buried rock, Merrild notes that the melting is not a driving factor for the increased interest in exploration. After all, glacier melting takes a long time.

Arctic sea ice extent has been decreasing over the past five decades. This aspect of climate change presents a strange dichotomy for Greenland – a warming climate means changing ecosystems, sea level rise, and the disruption of ocean currents. But it also means Arctic ocean passages are opening up, creating easier transport of critical minerals used in green energy technologies – which will hopefully slow climate change.

Merrild, who grew up in Greenland and has continued to work there on various projects, notes that while Greenlanders are not opposed to mining activities they have some worries. One concern is the land itself. In Greenland, the government owns and administrates land to residents. "In that sense, everybody owns the land and nobody owns the land," Merrild explains. As a result, closed, private mining sites are a cultural anomaly, and permissions or access limitations have to be carefully handled.

To foster cooperation with international companies and avoid missteps, Merrild says Greenlanders should be involved in the mining process from start to finish. "People see [mining] as an opportunity, but they would very much like to take part in the development, to be co-owners, and be a part of the planning of the project," she says.

So, is Greenland about to become the next Wild West? Denmark's Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen says that is up to the people of Greenland. But the international interest in their island is also unlikely to deminish any time soon.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.