The spacewalk that saved Hubble

Nasa

NasaHubble celebrates its 25th anniversary this month. However, the Nasa space telescope that has transformed our view of the Universe was launched with a major defect. Richard Hollingham talks to the man who had to don his spacesuit and make it work.

Story Musgrave had worked on the development of the Hubble Space Telescope from its inception in the mid-1970s to launch in April 1990. An astronaut, doctor and scientist (he has seven graduate degrees, including maths and medicine), Musgrave understood every system, instrument and component; every panel, nut and bolt. What he did not know, was the space telescope that promised so much had some serious quality control issues.

“Most of Hubble’s failures should never have happened,” Musgrave says. “It had so many darned problems as soon as it got into space.”

Nasa

NasaMost serious among a catalogue of flaws – including communications, component and electronic failures – was a fault with the primary mirror. An investigation concluded that, during manufacturing, the mirror’s edges had been polished slightly too flat. This meant the $1.6bn (£1.06bn) observatory was unable to properly focus.

By June 1990, when Nasa realised the seriousness of the situation, it described the mirror defect as a “spherical aberration”.

Famous failure

Four years after the Challenger disaster, Nasa found itself once again at the centre of a political storm and “negligence” was one of the milder words being bandied around by journalists, commentators and politicians.

Hubble became the butt of jokes, featuring in comedy stand-up routines. A picture of the telescope can even be glimpsed on the wall – alongside disasters including the Hindenburg and Titanic – in a blues club scene in the 1991 hit movie Naked Gun 2½.

If Hubble were a new car you would take it straight back to the dealer and demand a refund. But this was American taxpayers’ money and the faulty machine was in space. Nasa either needed to write it off or fix it.

Nasa

NasaFortunately, the agency had always intended that the space telescope would be regularly serviced and updated in orbit. That was why spacewalk expert Musgrave had been assigned to the project in the first place.

“During its development they told me to identify every possible failure it could get into and come up with the spacewalk and tools to fix each one of those failures,” Musgrave explains. “I did not identify [the mirror] as a possible failure… but I should have.”

List of flaws

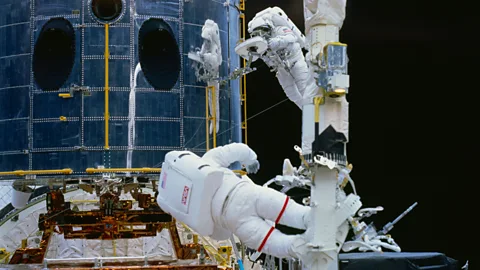

Now Musgrave was tasked with leading an Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA) team that would enable Hubble to fulfil its potential. By the beginning of 1992, while engineers developed a new instrument to counter the “aberration”, Musgrave’s team had started to plan the rescue mission.

As the crew began its spacewalk training in the giant water tank in Houston, the list of failures on board the ailing telescope was getting longer and the required repairs more numerous. As a result (and by Nasa’s own admission) Hubble’s first servicing mission, STS-61, was to become one of the most challenging and complex crewed spaceflights ever attempted.

Nasa

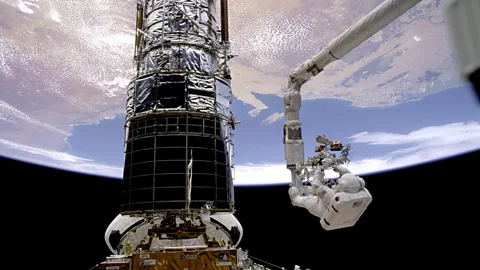

NasaSpace Shuttle Endeavour was launched on 2 December 1993. Three days later, the spacecraft rendezvoused with Hubble and Swiss European Space Agency astronaut Claude Nicollier used the robotic arm to capture the faulty telescope and park it in the payload bay.

The next day, Musgrave and fellow astronaut Jeff Hoffman donned their spacesuits to begin one of the longest EVAs in space history. Anchored to the robotic arm 600 kilometres (370 miles) above the Earth, they spent almost eight hours replacing gyroscopes, control units and electrical circuits. The only problem they encountered was closing the instrument compartment doors.

‘Follow the plan’

I ask Musgrave if the EVAs were hard. “They weren’t hard, they were easy,” says the straight-talking astronaut. “Hopefully you’ve had enough imagination on the ground to see how it’s going to be and then it flows very nicely,” he says. “We had very few surprises as we went along.”

“The real heroics of the fix were done on the ground, to get the details right – when you build a good plan, you follow the plan,” says Musgrave.

Backed by hundreds of engineers, technicians and controllers on the ground, during the 11-day mission, the Shuttle crew carried out five back-to-back EVAs, notching-up some 35 hours and 28 minutes outside the spacecraft. Musgrave and Hoffman carried out three spacewalks, alternating with their colleagues Kathryn Thornton and Tom Akers.

Watch how Hubble allows us to see further into the past than ever before in this clip from Horizon

If the problems with Hubble represented the worst of Nasa, then STS-61 showed the agency at its best. Despite the work involved, Musgrave even had time to appreciate his unique situation.

“You’re never too busy if you’re an explorer,” he says. “You’re looking at the Earth go by, you’re looking at the aurora, at the stars and you’re experiencing the doing itself. There’s no such thing as too busy.”

With a fully functioning Hubble Space Telescope released back into its orbit, politicians who had been so critical of Nasa became the first to congratulate the returning astronauts. In the years since, Hubble’s near-disastrous early years have been largely forgotten.

Landmark mission

The servicing mission transformed a media narrative of Nasa’s incompetence into one of triumph. In fact the serious glitches, faults and defects experienced by Hubble are now described in the history section of its official website as “teething problems” – an understatement, perhaps, given the potential gravity of the situation.

Nasa

NasaThanks to the crew and support staff of STS-61, Hubble has become one of the most significant and important space missions of all time. And, for Musgrave, the space telescope has become much more than a science mission.

“You look to the heavens for what the meaning of life is down here,” says Musgrave. “Hubble bridges a gap between cosmology, theology, philosophy and astronomy.”

“It tends to shed a light on who we are. And who humanity is.”