'Something stirring beneath the surface': What eight ghostly portraits found hidden inside masterpieces reveal

The Courtauld Institute of Art

The Courtauld Institute of ArtIn the past month alone, shadowy portraits have been found hidden in longstanding masterpieces by Titian and Picasso. What can they and other such discoveries tell us?

Something's stirring. Every few weeks, it seems, brings news of a sensational discovery in the world of art – of paintings hidden under other paintings and vanished visages twitching beneath the varnish of masterpieces whose every square millimetre we thought we knew. This past month alone has brought to light the detection of mysterious figures trapped beneath the surface of works by Titian and Picasso. But what are we to make of this slowly swelling collection of secret stares – these absent presences that simultaneously delight and disturb?

In early February, it was revealed that researchers at the Andreas Pittas Art Characterization Laboratories at the Cyprus Institute, using advanced imaging and a new multi-modal scanner combining different techniques, had proved the existence of an upside-down portrait of a mustachioed man holding a quill beneath the Italian Renaissance master Titian's painting Ecce Homo, 1570-75. On its surface, Titian's canvas portrays a bedraggled Jesus, hands bound by ropes, standing shoulder to shoulder with a sumptuously dressed Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor who will sentence him to death. What is this strange, erased, anachronistic scribe doing here and what is he trying to tell us?

The Cyprus Institute

The Cyprus InstituteThe presence of the hidden portrait, who peers imperceptibly through the craquelure – those alluring cracks in old master paintings – was first described by the art historian Paul Joannides and its significance to the surface narrative is more than incidental. While the identity of the topsy-turvy figure has yet to be determined, it is clear he helped shape the wrenching composition under which he has been buried for the past 450 years. The analysis of the materiality of the painting's layers in Cyprus has shown that the contours of the hidden figure's face dictated the curve of ropes binding Jesus's hands – establishing notes of harmony between the successive and seemingly contrary compositions.

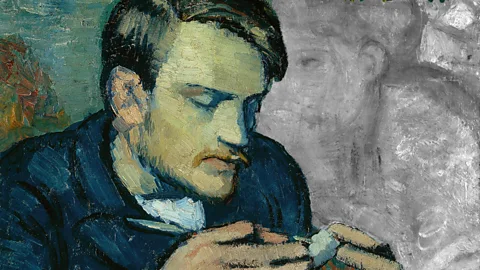

That sense of quiet collaboration between layers of paint – between what is there and what used to be there – is more striking still in the hidden countenance of a woman found by conservators at The Courtauld Institute of Art beneath a painting from Pablo Picasso's Blue Period – a portrait of the artist's friend and sculptor Mateu Fernández de Soto. Also discovered with the use of infrared imaging technology, the portrait of the as-yet unidentified woman is rendered in an earlier, more impressionistic style, and appears, when brought to the surface, to be whispering into de Soto's ear, as if the past and present had merged into a single suspended moment.

The Courtauld Institute of Art

The Courtauld Institute of ArtIn most instances, these buried portraits are merely the ghosts of rejected compositions that we were never intended to see – and could not have, were it not for the aid of advanced imaging tools that allow experts safely to peer beneath the paint without harming a work's surface. X-rays uncover hidden sketches, while infrared reflectography is capable of exposing subtle details masked by old varnish – details which, once glimpsed, are impossible to unknow. Once revealed, these portraits demand to be reckoned with. What follows is a short survey of some of the most intriguing and mysterious portraits – very often self-portraits – found wriggling restlessly beneath familiar masterpieces: unsettling presences that remain forever immeasurably close and worlds away.

Rembrandt's Old Man in Military

J Paul Getty Museum

J Paul Getty MuseumThink of Rembrandt and we tend to think first of that dim, imperishable realm in which his sitters sit outside of time – an eternal stage crafted from charcoal and sombrous umber. What we don't think of is giddy greens and garish vermilions igniting the space with vibrancy and verve. But that is exactly what researchers found staring back at them when they subjected the Dutch master's painting, An Old Man in Military Costume, to macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) imaging and infrared reflectography. Trapped beneath Rembrandt's meditation on mortality, a giddy ghost of jaunty youth clad in raffish reds and incorrigible verdigris intensifies the poignancy of his masterwork.

Artemisia Gentileschi's Saint Catherine of Alexandria

National Gallery, London

National Gallery, LondonWith some paintings, the more we see the less we know. Take Artemisia Gentileschi's portrait of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1619. X-ray analysis of the Italian Baroque artist's work undertaken in 2019 revealed that she began the work as a self-portrait – one that closely resembles an earlier, and similarly entitled, Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, begun around 1615. Disentangling the two works' faces is tricky but scholars now think that the final work – which swaps a turban for a crown and a piercing stare for a pious, heavenly gaze – blends elements of the artist's own likeness with those of Caterina de' Medici, daughter of the Grand Duke Ferdinando de' Medici, who commissioned the work. The result is proof that while an artist may be able to let go of a painting, a painting can never completely let go of the artist.

Caravaggio's Bacchus

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCaravaggio only signed one painting during his lifetime and did so with ghoulish flair in a squiggle of blood at the bottom of the largest painting he ever made, The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, 1608. But that is hardly the only time the Italian master inserted a semblance of himself into his paintings. In 2009, scholars using advanced reflectography penetrated the cracked surface of Caravaggio's depiction of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, to rehabilitate a tiny self-portrait that he had secreted in the reflection of the carafe (an almost subliminal detail that clumsy restoration efforts had obscured after the portrait-within-a-portrait was first discovered in 1922). This strange, distorted, now-you-see-it-now-you-don't selfie in the vessel of wine is key to the work's meaning, amplifying as it does themes of drunken illusion and elastic identity that are central to Caravaggio's painting.

Van Gogh's Patch of Grass

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA century before the late, great film-maker David Lynch unsettled viewers by taking them beneath a suburban lawn to find what is writhing in the soil in his film Blue Velvet (1986), Vincent van Gogh was busy burying things under his own deceptively sunny Patch of Grass, 1887. With the help of high-intensity X-rays from a particle accelerator, researchers succeeded in exhuming from beneath his sprightly blades of grass a sombre portrait of a peasant woman that the artist had painted years earlier. The discovery is further evidence that when it comes to Van Gogh, however joyful a work may seem, there is always something stirring beneath the surface.

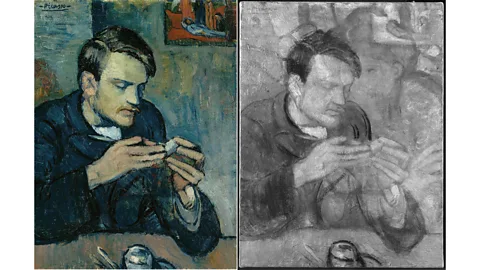

Seurat's Young Woman Powdering Herself

The Courtauld Gallery

The Courtauld GalleryOn the surface, Young Woman Powdering Herself is a playful meditation on how subject and style overlap. Here, Georges Seurat employs his pioneering pointillist technique of countless tiny dots to depict his mistress, Madeleine Knobloch, as she scatters her own flurry of powdery specks across her face. The dabs of paint seem to swirl in the air, all but clogging it – metaphorically powdering, too, anyone who stops to stare. These deftly deployed dabs of paint reveal and erase in equal measure, as if conjuring a world only to blot it out again. That sense of brilliant obliteration is intensified with the discovery of a hidden self-portrait – Seurat's only known one – in the open window which he later concealed beneath another flurry of dots depicting a vase of flowers. How dotty is that?

Modigliani's Portrait of a Girl

Alamy/Oxia Palus

Alamy/Oxia PalusSome people refuse to be forgotten, no matter how hard you scrub them from your memory. Italian modernist Amedeo Modigliani's famous Portrait of a Girl, 1917, is a compelling case in point. Some scholars suspect that the full-length portrait of a woman, concealed beneath the visible image, may depict an ex-lover with whom Modigliani ended a relationship a year earlier. In 2021, two PhD candidates at the University of London used Artificial Intelligence to reconstruct this hidden portrait, which strikingly resembles Modigliani's former muse and mistress, Beatrice Hastings. While the identity of both women, surface and hidden, remains uncertain, the layering reinforces themes of concealment and masking in Modigliani's work.

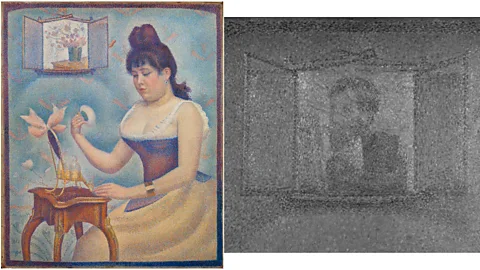

René Magritte's La Cinquième Saison

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de BelgiqueIn his painting La Cinquième Saison, 1943, René Magritte portrays in profile two nearly identical men in dark suits and bowler hats – props that often signal the presence of his alter-ego in the artist's work. Both men hold small, framed paintings under their arms as they walk towards each other. The trajectory of their strides suggests not so much an imminent collision as a near miss – an eclipse, as one figure and painting slips behind the other. It somehow seems fitting that this painting – this painting of shuffling paintings – has been found, with the use of infrared reflectography, to be hiding under its surface another painting altogether: a portrait of a mysterious woman, who at once bears a strong resemblance to the artist's wife, Georgette, and has features that are wholly distinct. The discovery of the hidden portrait merely amplifies themes of riddling duality in the work of an artist known for his treacherously teasing images.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.