How true is The Brutalist? The real-life history of Jewish immigrants in post-WW2 America

Universal Pictures

Universal PicturesA fictional story about the struggles of a Holocaust survivor in the US is favourite to win the best picture Oscar. Historians and experts, along with the film's star and director, discuss how accurate The Brutalist is.

When László Toth first sees New York's Statue of Liberty in the opening scene of Brady Corbet's film The Brutalist, it's upside down. It's 1947 and Toth, a Hungarian-Jewish architect who has survived the Holocaust, has arrived to start a new life in the US. The statue only appears to be upside down because of Toth's awkward perspective; but the visual inversion of America's historic welcome point for immigrants is a warning that this film is no success story about "the American dream".

The Brutalist, nominated for 10 Oscars, including best picture, best director and best actor (for Adrien Brody, who plays Toth) is, despite its historical setting, a fictitious story. Toth, who survived Buchenwald concentration camp, has been forcibly separated from his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) during the war and hopes she can join him. In his pre-war career, he was a brilliant student of the Bauhaus in Germany, and an architect of modernist public buildings in Budapest. But Toth's hopes of building a new life in the so-called land of opportunity are illusory. After working as a labourer, he finds patronage with Pennsylvanian entrepreneur Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) who commissions him to build a grand monument, but it's made increasingly clear to Toth that he is a Jewish outsider in this rural white Protestant society. He is brutalised by the Van Buren family emotionally and, in one horrifying scene, physically. "We tolerate you," Van Buren's predatory and sneering son Harry (Joe Alwyn) tells the architect, leading Toth to despairingly conclude to his wife, "they do not want us here".

The concept of the American dream was first popularised by writer James Truslow Adams in 1931, at the height of the Great Depression. It's an ideal that, in the US, everyone has the freedom and opportunity to make a better life but Corbet, an American himself, takes a sledgehammer to that idea in his three-and-a-half-hour film. "The American myth is something that is not frequently undressed, especially in this 'coming to America' fable that we have seen rehashed again and again," Corbet tells the BBC. "So, I thought it was important, even in narrative terms, to propose a story that starts off in familiar territory, but that ends up in more unchartered places."

Toth's struggle to build something lasting and true to his vision in The Brutalist is a metaphor for all artists, including Corbet himself – he worked on developing the film for seven years with writer and partner Mona Fastvold and delivered an impassioned speech calling for directors to have creative control of their movies at this year's Golden Globes. But Corbet has said that, inspired by the Brutalist architectural movement of the 1950s, he also set out to deliver a metaphor on how the immigrant experience can parallel artistic struggle.

"The film is about how the artistic experience and immigrant experience march in lockstep, which is to say that, in general, if someone moves into a suburban town in America and they don't look like everybody else, because of the colour of their skin or because of their beliefs or traditions, everybody wants them to get… out," Corbet told the Hollywood Reporter. "With Brutalism in the 1950s, when people were erecting these monuments, many people wanted them torn down immediately… Brutalist architecture is representative of something that people do not understand and that they want torn down and ripped away."

Universal Pictures

Universal PicturesThis style of architecture, which originated in the UK in the 1950s and is famous for its concrete structures, rough textures and geometrical angles, informed Corbet and Fastvold's creation of Jewish immigrant László Toth, who pours all his pain from the Holocaust into trying to realise an immense monument in a new land that does not welcome him.

Corbet says that he believes that there's a link between post-war psychology and post-war architecture after 1945. "I did think, 'I think it's time for a film on Brutalism'," Corbet tells the BBC. "I read a lot on the subject, and there's an extraordinary book called Architecture and Uniform by the academic Jean-Louis Cohen that really examines the relationship between post-war psychology and post-war architecture, and the ways in which materials that were developed for life during wartime were eventually incorporated into many of these buildings in the 1950s."

Generational trauma

Corbet has Jewish heritage through his mother, but when asked recently by The Jewish Chronicle if the film was a reflection on rising antisemitism, Corbet replied: "The movie is about generational trauma… the immigrant experience is a mostly universal one. I don't know anyone that hasn't been affected by it, or whose family hasn't been affected by it, in one way or another."

The reason he chose to make his story about a Hungarian Jew was, he says, to be faithful to the famous Bauhaus school, established in the 1920s in Weimar Germany by Walter Gropius, and where many of the ideas around Brutalist architecture emerged. "It was predominantly central and eastern European Jews that were at the Bauhaus school before the Nazis shut it down in 1933," Corbet explains. He adds that he asked Cohen if there was a real-life example of one architect who reflected Toth's survival through Nazi occupation and imprisonment. "But in reality," Corbet says, "there are no actual examples of any of them who got stuck in the quagmire of war, survived and then managed to build up their practice again."

Instead László Toth is based upon a few key Jewish artists of the Brutalist movement, who all left Europe before World War Two and thus did not experience the Holocaust. They include Estonian Louis Kahn (who emigrated to the US as a child in the 1900s) Mies van der Rohe, who came to the US in the 1930s, and, especially, Hungarian-born Marcel Breuer, who designed the Met Breuer Museum in New York City. He, Corbet tells the BBC, was helped to the US in 1937 by Gropius, "but many others were not so lucky," he adds.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome architectural experts have spied the similarities between Toth and Breuer, including in Breuer's real life struggle to realise a Brutalist church, St John's Abbey in Minnesota, perhaps a nod to the Christian church and community centre Toth is commissioned by Van Buren to build in Pennsylvania. The film has been heavily criticised by some architects for being unrealistic. They point out that these particular Jewish architects who came to the US "built very successful careers, receiving deanships at major universities, and shaped the following century of modern architecture. None had to queue for bread [as Toth has to in The Brutalist]."

None of Corbet's films to date, however, have featured real-life protagonists (2015's The Childhood of a Leader was about the boyhood of a fictitious fascist dictator and 2018's Vox Lux was about a made-up pop star) and he tells the BBC that The Brutalist too is "a virtual history". Instead, he says, he wanted to pay tribute to those whose work was lost through the Holocaust. "My production designer, Judy Becker, and I have looked at many unrealised projects from designers out of the Bauhaus that didn't live long enough to ever see those buildings erected," he says. "The way that we think about the film was that it was a monument to them, and the ghosts of their unrealised work."

Michael Berkowitz, a professor of modern Jewish history at University College,London, and the author of Hollywood's Unofficial Film Corps, about Jewish film-makers during World War Two, describes The Brutalist as "in some ways, more historical as a piece of fiction than a lot of more supposed factual narratives".

"What I found most impressive about The Brutalist, somewhat sad to say, is how miserable Toth was," he tells the BBC. "And that he did have a hard time finding a professional outlet and how dependant he was on patronage. I found it refreshingly honest in that respect."

Universal Pictures

Universal PicturesArchitecture, he points out, was an established profession in the US in the early 20th Century, and one minorities or immigrants would have struggled join. "It wasn't the kind of field that Jews generally would have been drawn to, because it was seen as something that wasn't terribly accessible," he says. "It's easy to talk about antisemitism [as the cause] but it's more complex: in the way universities recruited, women did also not come into this field until quite late; there's only a small number of architects from minorities. It's so far deeply part of the culture as to who gets to construct buildings and who has the resources to do it."

Berkowitz thinks Marcel Breuer's own success was "very importantly" aided by having (the non-Jewish) Walter Gropius helping him to secure positions in the US, and points out that Louis Kahn arrived in the US as a child, and "studied at the University of Pennsylvania, an elite institution that happened to be more open to Jewish people in the US than a lot of other places. He certainly was not in a concentration camp; he couldn't have had a more different experience."

Antisemitism in 1940s US

In the US of the 1940s, many top American universities still restricted their intake of Jewish students, and some hotels, in addition to discriminating against black Americans, operated a "no Jews" policy as well. There is also evidence of a far-right Irish Catholic group, The Christian Front, violently attacking Jewish people, especially in Boston and New York, during World War Two. In 1939, a pro-Hitler organisation, the German American Bund, held a rally for 20,000 people in Madison Square Garden in New York, with Nazi swastikas surrounding a backdrop of George Washington.

Even legendary director Stanley Kubrick, born in the Bronx, New York, in 1928, was once refused a restaurant table because of his Jewish heritage, according to historian, academic and Kubrick biographer Professor Nathan Abrams. American aviator Charles Lindbergh blamed Jewish people for controlling the US media in an infamous 1941 speech; Abrams argues that Hollywood's then nascent film industry, founded mainly by Jewish immigrants (seven out of the eight original studios were started by Jews from Eastern Europe) was an anomaly in terms of its influence.

"Hollywood was allowing Jews to progress in an industry where they wouldn't get the breaks otherwise; it was willing to accept them because originally the industry was considered so new and faddish that it wasn't going to last," Abrams tells the BBC.

Toth and his family certainly experience antisemitism in The Brutalist, both overtly and covertly. His spirit is steadily crushed as the film progresses. He arrives in the US hopeful about his future, and sleeps in his Jewish cousin's warehouse storeroom, but his cousin's Catholic wife cannot tolerate him. Lonely for his own wife, but unable to bring her into the country due to tough immigration laws, Toth turns to heroin for relief, and by day does hard manual labour to survive.

"Why is an accomplished foreign architect shovelling coal in Philadelphia?" is the question Guy Pearce's character asks Toth, when he tracks him down.

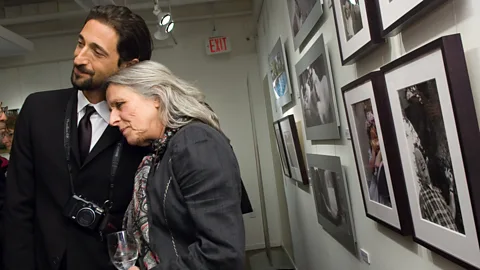

That Toth, though eager to assimilate and succeed, finds the reality soul-destroying, resonates with Adrien Brody, who previously won an Oscar in 2003 for The Pianist, the story of a Jewish musician during World War Two. His family has direct experience of fleeing persecution – Brody's mother is New York photographer Sylvia Plachy, born in Hungary to a Jewish mother and Catholic father. She came to the US in the 1950s as a teenager after the Hungarian Revolution. His father, Elliot Brody, is of Polish Jewish descent.

Getty Images

Getty Images"There was a lot that I could relate to personally, my own mother and grandparents' struggles of fleeing the hardships of war and immigrating to the United States in the 50s, and the artistic yearnings to leave behind something of great significance with my work," he tells the BBC.

"And there is a disconnect between the hopes and dreams of [Toth] fleeing oppression and hardship and then arriving in a land with the fable of what is attainable, and the harsh realities. I think the other hardship is to long for a sense of belonging and home, especially if you're leaving a place where your home is taken from you. And then to work to contribute and help build a nation, and to still somehow not to be treated with the same level of respect and equal worth? I think that's a lot."

Brody also recalls his childhood growing up "in Queen's, [a borough of New York City] built by immigrants and filled with people who mostly keep [the city] intact and alive. I grew up with the understanding of my mother, the journey of an artist and assimilation into this great country, of her being an outsider. And my grandparents struggled with language barriers and finding work that was meaningful: I grew up close to them and their journey was harder [than my mother's]".

More like this:

• Will offensive posts derail an Oscars favourite?

Those first-generation Jewish immigrants who had survived the Holocaust, often struggled internally as well as facing social barriers, Berkowitz says. Also the author of a book examining the Jewish relationship with photography, he gives the example of Romanian-born photographer Magda Szirtes, who survived Ravensbrück concentration camp and who came to Britain after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, but who took her own life at the age of 51.

"Her son, George Szirtes, a successful poet and translator, wrote a memoir, The Photographer at Sixteen, about his mother, who was a very talented photographer who was never able to reconstruct her career. And in some ways, the kind of life she had is similar to The Brutalist. Probably most Jewish women I've looked at who were really talented photographers, were not able to reconstruct their careers after the war in either the US or Britain, although some did manage."

'A slow change of attitudes'

Like many immigrants fleeing persecution, and indeed László Toth himself, first-generation Holocaust survivors had to start again in society, often at the bottom, Berkowitz adds. "Professional Jews from central or Eastern Europe who emigrated after the war, a lot of them worked as butlers or cleaners, and these people had very sophisticated educations. We like to hear success stories, but we don't hear about, say, somebody's uncle who was an engineer who ended up cleaning kitchens."

Even the Nobel Laureate and Holocaust survivor, writer Elie Wiesel, who arrived in the US in 1956, "was not listened to in the early days, and he writes about that," says Professor Tony Kushner, an expert in refugee studies at the University of Southampton. "It was a slow change of attitudes after the late 1940s. There isn't this concept we have of a Holocaust survivor today of being someone of enormous importance and significance. It was just, 'get on with your life'," he tells the BBC.

As The Brutalist shows by the length of time it takes to get Erzsébet Toth (played by Felicity Jones) into the US, and then only because of Van Buren's family influence, many Jewish immigrants struggled to get into the country at all. The Harrison Report of 1945, carried out by the US government to advise on the conditions of what was known as the "Displaced Persons" (war refugees) camps in Europe, recommended reconnecting Jewish people with family in the US, if they had any. The United States admitted 400,000 people between 1945 and 1952 after The Displaced Persons Act of 1948, and approximately 80,000 of them were Jewish.

Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures"Jewish survivors represented a quarter of the people in Displaced Persons camps in Europe, but less than a quarter of those who were allowed entry," Kushner says. "There were certain racial stereotypes and assumptions about them, the idea of Jews being shopkeepers, pedallers, tailors, not able to be farmers or work on the land, not to be productive basically."

"It remained a huge problem also going through the kind of paperwork and mechanisms that you had to do in order to get someone over," adds Michael Berkowitz. "My own family had a cousin who was a refugee first in Britain, and they tried forever to bring her over to the US. They never succeeded in even bringing her from London. The family had no connections. If you didn't have the wherewithal, you couldn't do it, it was almost impossible."

Toth eventually unveils his masterpiece in the rolling Pennsylvania hills: a building inspired by the Nazi concentration camps where he and Erzsébet were held, the seemingly infinite corridors an expression of his longing to reach his wife. Through the horror of all his experiences, he has stuck to the purity of his artistic vision. That purity is something that Corbet can relate to – after struggling to make the film he wanted to for seven years, The Brutalist is now poised as the favourite to win best picture and best director Oscars, and the film itself is a monument to a movement born through struggle.

The Brutalist is in cinemas now.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.