'Clothes can contain a lot of emotion': How black men have used flamboyant fashion to express pride and resistance

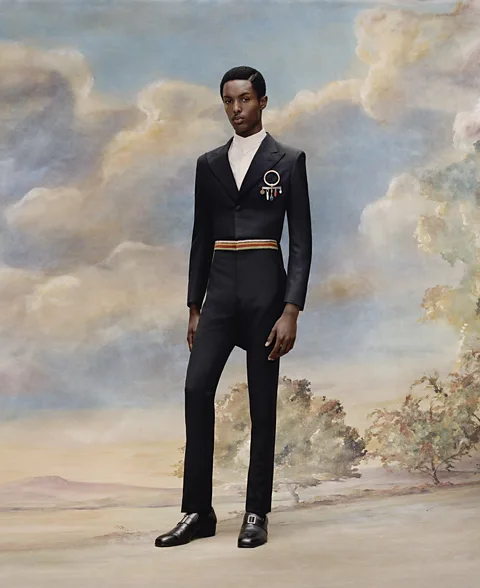

Tyler Mitchell

Tyler MitchellThis year's Costume Institute spring exhibition and Met Gala are honouring black "dandy" style, and the tradition of bold tailoring worn by black men that has made a statement.

Black dandyism, the subject of the Costume Institute's much-anticipated spring 2025 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, is a rich theme. A dandy is a flamboyantly dressed male figure who is concerned not only with looking good but with making a statement about his identity and individuality. And black dandyism is a defiant declaration against confinement, a celebration of black identity, and a movement based around resistance, pride and history.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

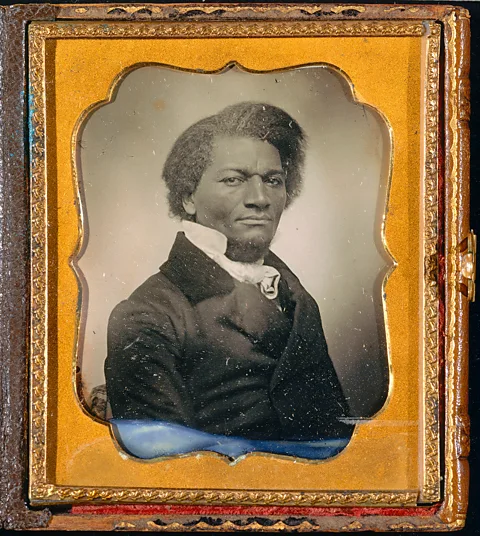

Metropolitan Museum of ArtThe story of black dandyism does not begin with clothing but with the absence of it. Enslaved Africans, writes Monica L Miller in Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity (2009), "arrived in America physically and metaphorically naked, a seeming tabula rasa on which European and new American fashions might be imposed". Dandyism was a critical response to this, and was born out of a desire to self-define and envisage new social and political possibilities – in a context where the very concept of "blackness" was created by non-black oppressors.

Inspired by Miller's seminal book, the exhibition examines how men's style, and in particular, dandyism, has helped shape transatlantic black identities for more than 300 years. The star-studded Met Gala in New York, which takes place on Monday, takes the corresponding theme "Tailored for you" as its dress code. Co-chairing and hosting the event are actor Colman Domingo, Formula One driver Lewis Hamilton, rapper A$AP Rocky and musician and creative director Pharrell Williams. They will work with Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour and honorary co-chair, basketball player LeBron James.

The show features garments, artworks, photographs and film, and explores 12 different characteristics of dandyism, ranging from Ownership, Heritage and Presence to Respectability, Beauty and Cool. The "superfine" in the title, says Miller, who is guest curator of the exhibition, pertains to "a finely woven wool, which we're using as an expression of luxury, but also feeling 'superfine'" – a reminder that how you dress can contain "a lot of emotion".

Courtesy Internet Archive

Courtesy Internet ArchiveIndeed, one of slavery's first acts of debasement was to strip the enslaved of their own clothes, and dress them in standard-issue clothing. "Everyone was supposed to look exactly the same," Miller tells the BBC. "It was a vehicle of dehumanisation, but people immediately affixed buttons, ribbons, modified the garment a little, literally tailored it so that it could be individualised." Dandyism was already laying its foundations.

In the 17th and 18th Centuries, for enslaved Africans brought back to Europe as domestic servants, control was once again asserted by their masters – in some households they were dressed up in ostentatious, deliberately anachronistic livery, their masters objectifying them in order to signal the family's wealth. Some were educated alongside members of the host family, whose guests were amused to see someone of colour speak and act like a gentleman.

However, in the case of Julius Soubise – manumitted (released from slavery) in the 1760s by his British mistress, the Duchess of Queensbury – the joke was on the aristocrats. Soubise reclaimed and exaggerated the flamboyant clothing that his mistress had made him wear by adding diamond-buckled red-heeled shoes, lace frills and clouds of perfume, and his subversive, startlingly feminised dandyism created shockwaves among white society. Educated, witty and charming, and a capable equestrian, fencer and violinist, he destabilised established categorisations of race, gender and class, and forced a reimagining in the white consciousness of what a black man could be.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

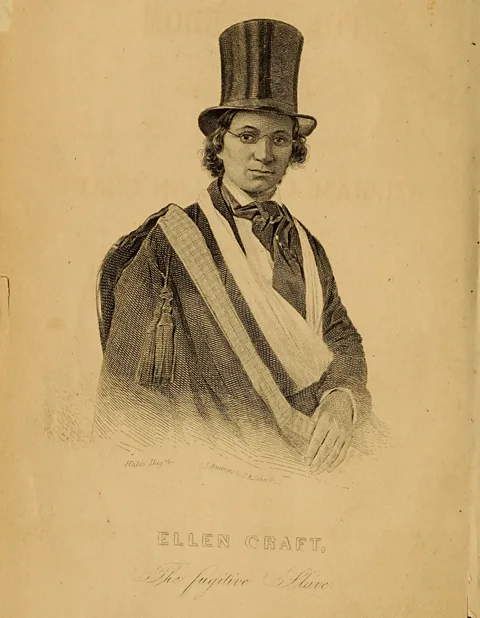

Metropolitan Museum of ArtWhile Soubise used dandyism to assert visibility, elsewhere in the exhibition, dandyism is shown being used for concealment. It was a form of dressing up that enabled William and Ellen Craft to escape slavery in Georgia in 1848, as told in William's 1860 memoir. Transgressing – once again – boundaries of race, gender and class, Ellen, the daughter of an enslaved woman and her slaveholder, disguised herself as a white invalid gentleman – complete with jaw bandage and sling, and green-lensed spectacles – in order to escape her captors, while her husband William was passed off as her servant. When William, with freedom in sight, dandified himself with "a very good second-hand white beaver [top hat]" the pair's cover was almost blown, drawing comments from a disgruntled planter that his "master" was spoiling him. Their escape succeeded, and the two went on to build a new life across the ocean in England.

Later, with the abolition of slavery in 1865, the Crafts were emboldened to move back to the US, while other black Americans began relocating from the rural South to the expanding cities of the North, establishing, for the first time, large black urban communities. One of these was Harlem, New York City, which, during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 30s, became a centre of creative expression and a manifestation of the black freedom that so many had dreamt of.

A historical throughline

In forging a modern black identity and standing up against lynchings, riots and persistent discrimination, dressing up again played a central role. In 1917, around 10,000 African Americans took part in the Silent Protest Parade down New York's Fifth Avenue, the men in black tailored suits, the women and children dressed in white. It was a display of respectability, calm and control that contrasted with the savagery of the violence perpetrated against them.

Thomas Hoepker/ Magnum Photos

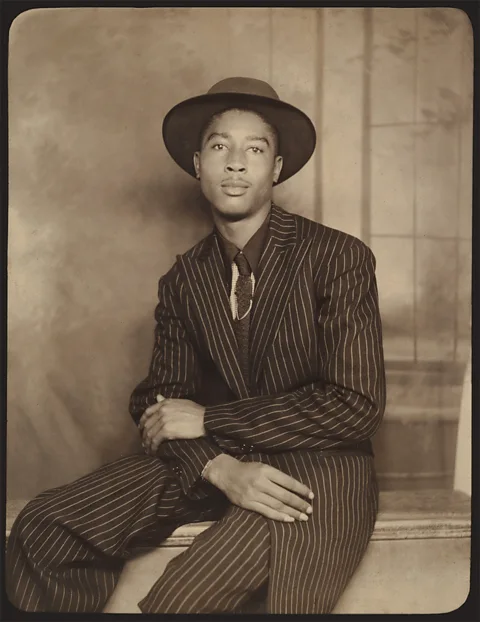

Thomas Hoepker/ Magnum PhotosThe suit, explains Miller, is "a historical throughline" in the exhibition, which includes everything "from livery garments… to tailcoats and different versions of it… to even track suiting". One of the most dandified examples is the zoot suit, which debuted in Harlem's dance halls in the 1930s before spreading across the country. Donned by performers such as Dizzy Gillespie and Cab Calloway, as well as the activist Malcolm X, it featured oversized shoulder pads, wide lapels and ballooning trousers cuffed at the ankle, and was often accessorised with a pocket watch on a long chain and a brimmed hat. Its sheer voluminosity seemed symbolic of a burgeoning black community's desire to take up their own space and to move with freedom.

When rationing was introduced in the 1940s, this expression of counter culture became a source of supposed indignation due to the amount of fabric the zoot required. This became a pretext for further violence against people of colour, particularly in Los Angeles, where white mobs stripped people of their suits and slashed the fabric with knives. But the zoot suit was too strong a signifier of black sartorial elegance to be entirely subdued, and has continued to reassert its importance, reappearing as the trademark style of the musical group Kid Creole and the Coconuts in the 1980s, for example, and later inspiring rapper MC Hammer's iconic baggy-crotched "Hammer pants".

Described by Anna Wintour (editor-in-chief of US Vogue) in a recent article as "a dandy among dandies", André Leon Talley (1948-2022), the first black creative director at US Vogue, was born at the tail end of the zoot suit's reign, and went on to become one of fashion's black luminaries. His favourite photo of himself, taken in the 1980s, appears in the exhibition, along with the panel-checked Morty Sills suit he is wearing. Later, he would become known for his luxurious swooshing capes. "He understood that, especially as a black man, what you wore told a story about you, about your history, about self-respect," writes Wintour. "For André, getting dressed was an act of autobiography, and also mischief and fantasy, and so much else at once."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor Nigerian-American artist, photographer and writer Iké Udé, whose self-portrait appears on the cover of Miller's 2009 book, the construction of self through fashion is a critical reaction to negative perceptions of it. "Whereas the self can be devoured by public scrutiny, it can be saved by private self-objectification," he writes in his 1995 essay The Regarded Self. In Sartorial Anarchy #5 (2013), part of a series of self-portraits by Udé, we see a pastiche of dandyism that both embraces this display and satirises it. "He's wearing male dress in all of those portraits but from different time periods and geographies," explains Miller. "It's a real manifestation of cosmopolitanism and wit."

This theme of cosmopolitanism continues in the clothing of award-winning designer Foday Dumbuya, whose brand Labrum reflects his own journey from Sierra Leone to Cyprus and England, and features the tagline "designed by an immigrant". Much of his work celebrates his African heritage, and uses sharp, sartorial design to challenge negative associations with Africa and with migration. "He's designing garments that often use immigration documents from his own family or from other people that he incorporates into the printed silk fabric," says Miller. The idea for the exhibition began, she adds, with an observation by the curator of the Met's costume collection, Andrew Bolton, "that there was a kind of renaissance going on in menswear and black designers were really at the forefront of that".

Tyler Mitchell 2025

Tyler Mitchell 2025Black dandyism, maintains Miller, is part of a culture in constant movement. "Black people are always trying to outrun stereotype and appropriation, and if we take it all the way back to the 19th Century, they're trying to outrun capture, so there's a way that that's built into the culture." Consequently, dandyism shows no signs of dwindling. "It's very much related to a jazz riff," Miller adds. "Somebody puts that down, somebody picks that up, modifies it, changes it, it becomes something new…"

Superfine: Tailoring Black Style is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City from 10 May to 26 October 2025. The accompanying book by Monica L Miller is published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.