The vandals who ruin the art they love

Getty

GettyArt moves some to tears, some to anger, and on very rare occasions it stirs acts of passion. These are the people who damage artworks with affection, writes William Park.

The destruction of art is often politically motivated – it can even be hate-filled. Art should move people emotionally, and when that emotion is anger it is possible to see why some people resort to vandalism. High-profile artworks come to represent national identities, symbols of the people who keep them or of the museums in which they are held. The Mona Lisa has been the target of vandalism on numerous occasions. Once, by a woman denied French citizenship. Another time, while out on loan, by someone frustrated with the Tokyo National Museum’s lack of disabled access.

But, at the São Paulo International Biennial in 1996 something unusual happened. A painting was damaged, not out of anger, but out of affection. And it demonstrated something powerful about how we appreciate art.

More like this:

One painting from Andy Warhol’s 1977 series Torsos was at the Biennial that year. The series features paintings and photographs of male and female nudes, sometimes contorted, sometimes straight on, extending from midriff to mid-thigh. The work on show in São Paulo included a front-on male nude repeated six times.

Getty

Getty“I get a call one morning to say ‘You will not believe what happened,’” says Ellen Baxter, Chief Conservator at the Carnegie Museum of Art. “This Brazilian was so overwhelmed by her feelings for Andy that she planted a kiss on one of the male bits.” A contemporary news article from a Brazilian daily newspaper noted that the kiss was placed “on the central part of the first torso, on the penis.”

“The Torsos are really provocative, private images,” says Jessica Beck, a curator at The Andy Warhol Museum. “They’re beautifully lit, too. It’s easy to see why someone would have a strong, emotional, passionate reaction to them.”

The perpetrator was not apprehended, nor were they ever identified, and the lipstick was removed without much fuss. Baxter remembers that security guards at the Biennial shared video footage of the act, which appeared to show an older person “dressed to the nines” in a black sheet and jewellery, kissing the painting.

“I don’t think there was anything political about it” says Baxter, of the act. “I think she just thought it would be cute.”

Imagine, then, Baxter’s reaction when the same thing happened at The Andy Warhol Museum, where she was paintings conservator. Only this time, the kiss was not going to be as simple to remove.

‘An act of love’

In 1997 The Warhol Museum played host to a 75th anniversary party for Chanel No 5. Warhol had used a bottle of the famous perfume in some of his prints, which were later used as the artwork on the boxes of a special run of the perfume. It did not occur to anyone that a guest might get a little drunk, take a red Chanel lipstick out of their gift bag, put it on and return to the museum to kiss a bath.

“My first thought was ‘Oh crap, how stupid’ and then ‘Why would anyone kiss a bathtub?’ I’m not advocating kissing Elvis or Marilyn, but this didn’t make any sense at all,” says Baxter.

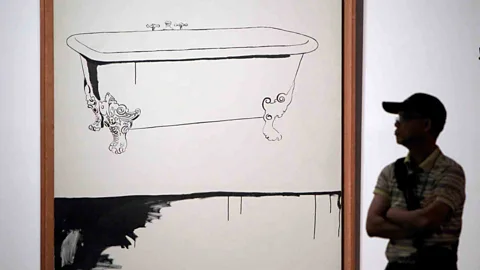

The painting in question is Bathtub: one of the early hand-painted Warhols, a very lightly primed canvas with a simple bathtub drawn on in ink. “The surface is raw,” says Beck. “It’s from the 1961/62 moment when he paints in a townhouse with a projector. Warhol is working with adverts, projecting them on to canvas and painting over them.”

Nasa

Nasa“Unfortunately, typical conservation solvents would drive the lipstick into the canvas,” says Baxter. “The canvas absorbs any moisture, so the lipstick sticks to the surface and if you’re not careful you can make it a lot worse trying to remove it. It’s like taking lipstick off a Kleenex.”

This act of vandalism was going to require specialist treatment. A previous conservator had spoken to someone at Nasa who had been using atomic oxygen to clean heat-proof tiles used on satellites. High in the Earth’s atmosphere, UV radiation splits O2 into individual oxygen atoms. These atoms are highly reactive and will bond with organic matter. The tiles were put in a vacuum chamber, exposed to atomic oxygen, and then cleaned with much greater ease after the gas has reacted with the dirt on the surface.

It took eight hours to clean the kiss off, fibre by fibre. It worked a bit too well in terms of the final result. The treatment also removed airborne pollutants that had darkened the canvas over the years. It was too clean.

Bathtub is a less common example of Warhol’s free-hand painting. In cleaning the painting too thoroughly you risk losing some evidence of that. “Intimacy is in a lot of early work from Warhol,” says Beck. “There are the gesture marks of Warhol’s hands at the bottom of the canvas. The Bathtub was from before he went clean-line and you lost those marks.”

Beck adds that while not an obvious choice for an affectionate vandal, in some ways Bathtub makes a lot of sense for someone to have an intimate emotional reaction. “I think it’s particularly interesting that it isn’t an image of a person. But it’s a reference to a body without the body. It’s implied. Bathtub is symbolically about a private moment – bathing. It can be a seductive experience, a sexual experience, too. Whereas Torsos are more conventionally pornographic images.”

Getty

GettyAgain, the perpetrator faded back into the party without detection. It was probably for the best considering the value of the painting and the potential cost of restoring it. A vandal in France was not so lucky; they were apprehended and fined for kissing a plain white canvas by Cy Twombly in 2007. At the trial, the vandal, Rindy Sam, said she was overcome with passion for the artwork. "I just gave it a kiss. It was an act of love, when I kissed it, I wasn't thinking. I thought the artist would understand," said Sam.

Why paintings elicit tears of joy

Affection for art can show itself in ways other than kissing. More commonly, audiences are moved to tears by art, and this reveals something about how we appreciate art in the flesh. James Elkins discusses the religious aspect of feeling moved by art. It is not too much of a stretch to see that people who are moved to tears by religious iconography might also feel affectionate. Kissing statues or icons is not uncommon in these contexts.

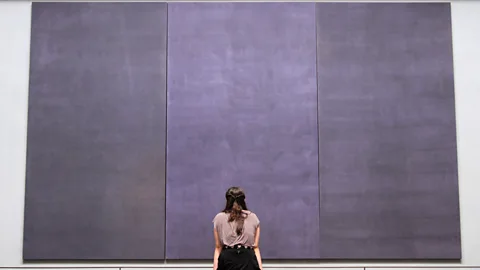

Even artworks that are not religious might have a similar effect on their viewers. Elkins gives an example of Jane Dillenberger, an art historian, who paid a visit to Rothko in his studio to look at several unfinished canvases. The canvases were almost 15ft (4.5m) tall and darkly painted. The studio, too, was dark, and seeing the canvases rise up out of the gloom generated an overwhelming experience for Dillenberger. Elkin writes: “...she was crying, and the two of them remained that way for several minutes: the art historian looking at the canvases through a blur of tears, and the painter smoking, watching her. It was a moment, she told me, of “very strange feelings,” but mostly of relief, of perfect ease, of pure peacefulness and joy.”

Beck says she has those moments. Warhol’s Shadows, an epic series of 102 prints of the same coloured, shadowy figure on a dark background, do it for her. The paintings are rarely displayed together in their entirety, but even 50 or so will fill a large gallery space. Their magnitude moved her to tears. It is an experience that you can only have seeing them in person.

Alamy

Alamy“I find them really emotional,” says Beck. “Museums are important because you can have these surprising, positive, emotional reactions. Even if there are boundaries with how you can behave, even with that, having access can transpose you.”

What would Warhol have made of these vandals? Beck suggests he would have enjoyed the choice of red lips. They evoke the bright red lips of his Marilyn prints from the 60s. The act of kissing might have appealed, too. Warhol worked with body fluids, notably urine on canvas in his Piss Painting (1961) and later semen on cotton in Cum (1977-78). The exchange of lipstick to canvas is not far removed from the work Warhol did himself.

Warhol was interested in spectacle, too, so the event itself might have interested him. “He loved openings and parties,” says Beck “He might have wanted to have a photograph of that moment, of the kiss. He had an interest in his last 10 years of photographing parties and vacations. He would have enjoyed that it was a social experience and [been] intrigued that a guest found a moment in the party to be alone and intimate with a painting.”

Modern artists, in pushing the boundaries of what we consider art, tempt reactions from their audience. Some unfortunately have their art destroyed as a result. Few are lucky enough to elicit such strong feelings of affection that their audience cannot help but give them a kiss.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.